Under the Banner of Chinggis Khan

A legendary military leader, the founder of the great Mongol empire who stands among the greatest conquerors along with Alexander, Caesar and Napoleon. Who doesn’t know him? And though for many of our contemporaries Chinggis Khan is no more than a mythical character from the distant past, for the greater part of the Mongolian world his name is a major component of the modern ethnic culture.

The words “Chinggis Khan” and “Mongol empire” have become mythologemes: that is, the classical myth with its plot, symbolism and ritual has been knowingly transferred into the modern ethnic culture. Memories of the great and glorious past — the Golden Age of the Mongols — are becoming an essential part of the nation’s life. Such a form of expressing ethnic identity, that is to say, the emotional attitude to the fact of belonging to an ethnos, always gets intensified in the periods of social and political crises like the one we are going through at present.

And his body turned into an ongon, a genius guardian…

The charismatic personality of Chinggis Khan started to play a great role in the public display of Mongolian identity as far back as in the 13th century, after his death. The Mongol tradition, similarly to other nations, attaches a great symbolic importance to the burial place of a forefather, in particular of such a great one: these were the forefathers that united all the parts of the cosmos together in space and time, as they were believed to be the center of the cosmological model of the world.

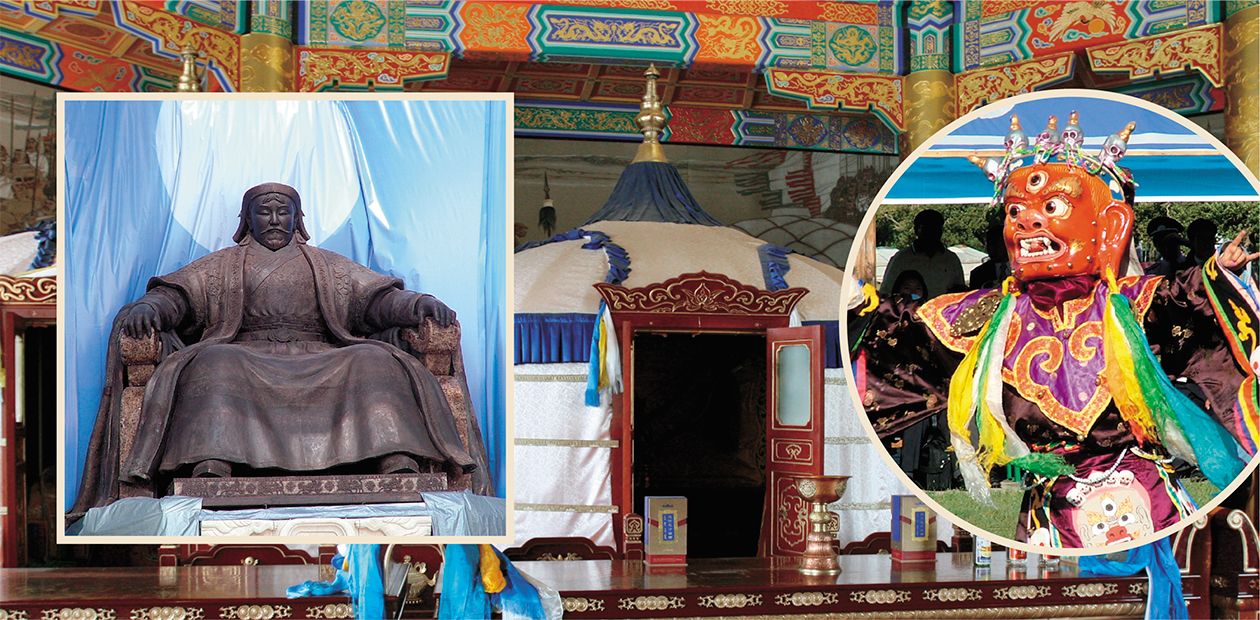

Worshiping Chinggis Khan in the place of his presumed burial is attri¬buted to the sacral character of his personality: according to traditional ideas, his body turned into the genius guardian ongon. Though the exact burial place of Chinggis Khan remains unknown, both Edzhen Khoro in the desolate Ordos desert near the Hwang Ho river in Inner Mongolia, an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China, and Deliun Boldok in Khentey, Mongolian Republic, which is also known as the place of his birth, are worshipped as such.

Like many other nations, Mongols traditionally believe that the burial place of a forefather, a great one in particular, is sacred.After Chinggis Khan’s grandson Khubilai was elected the Great Khan in 1260, he authorized the national cult of Chinggis Khan, also known as “the cult of eight white yurts”. Edzhen Khoro in Ordos became a place of worshiping forefathers, and annual offerings have been held there ever since.

The old custom of worshiping Chin¬ggis Khan in Edzhen Khoro partially comes from the following mythological event: in order to ensure a victory, Chinggis Khan and his many soldiers danced under a spreading tree in the grove of Thousand Trees, and after that made an offering to the banner (sülde). From then on, it was recommended to make an elm staff out of a tree growing in the grove and conduct a banner worshipping ceremony every year of Dragon (Altan Ordon, 1983).

The cult of Chinggis Khan, or “the cult of eight white yurts” was established by his grandson Khubilai in China almost 750 years ago.The cult of eight white yurts

In the past, the Edzhen Khoro memorial represented eight white yurts where Chinggis Khan’s relics were kept. Each of the yurts was dedicated to one of the great forefathers: ¬Chinggis Khan, his four sons Ögödei, Juchi, Chagatai, Tolui, the grandsons Güyük and Mengü, and also to his parents Esugei and Oelun.

In the mid-fifties of the last century a new memorial complex was built in Edzhen Khoro; it was ¬reconstruc¬ted in the 1990s and greatly enlarged in the last years. Important sacred attributes were added to the eight white yurts’ relics — Chinggis Khan’s banners, which are traditionally be¬lie¬¬ved to contain his charisma.

Sanctity of the memorial complex in Edzhen Khoro is emphasized by the fact that it has been the scene of annual New Year ceremonies and election of new rulers. After the Empire created by Chinggis Khan fell apart, the idea of Mongolian political unity was supported through conferring the Khagan title, which made claims to supreme power legal and fully agreed with the Mongolian political tradition developed back in the 13th century. An important role in power legitimization belonged to the Chinggis Khan memorial established at the same time. Mongolian chronicles of the 17th century accompany each entry on a candidate’s accession to the Khagan throne with the phrase: “obtained the Khagan title in front of the white yurts”.

In “the eight white yurts” memorial, New Year ceremonies and elections of new rulers have been held for centuries.

A remarkable example of supreme power legitimization in front of “the eight white yurts” at “heavens’ will” is the story of Togon Taishi, the head of oirats (nomadic people living in western Mongolia), who conquered Mongolians in 1438. The candidate for the title of the supreme ruler, “after defeating the Mongolians and getting swelled headed, [went to] observe the worshipping ritual in front of the eight white yurts of the Lord. He said upon arrival: ‘I will seize the Khan’s throne!’, observed the ritual and became a Khagan. Exhilarated by the Lord’s mercy, Togon Taishi shouted: ‘If you [Chinggis Khan], the august [lord] have greatness, I, Khatun’s descendant, am also great!’ He hit the master’s small tent and yelled. Then Togon Taishi turned round to go out — and blood was running down from his nose and mouth… When they had a closer look, it appeared that the eagle-feathered arrow in the ruler’s quiver was -moving and blood was trickling down it… he died” (Loubsan Danzan, 1973, p. 269).

Fill the golden vessel with mare’s milk…

White yurts were under the authority of the special group of darkhats, who kept the relics and traditions of observing the annual ceremony. In order to learn how the annual ritual of Chinggis Khan’s cult was held in Edzhen Khoro, one can read the description left by the Buryat scientist Ts. Zhamtsarano, who attended the great celebration on the 21st day of the second spring month (April) in 1910.

Before that day, 1.5 versts [1 verst is 3,500 feet] to the north-east of Edzhen Khoro, on the Bayan Chonkhook River, the sacred things were gathered: a trunk with Chinggis Kan’s relics, which was transported in a special yurt on the chariot harnessed by three white camels; and chariots of his second and two youngest wives. The yurt with Chinggis Khan’s relics was placed on the ground, to the northwest of it was a small yurt for the bow and arrows, in front of which grooms were on sentry with four palomino horses. The yurts of the wives were placed on the line of the main yurt.

Participants of the ceremony walked round all the relics clockwise, worshiped them and made a sacrifice. Jinon (the head of the darkhats) and his retinue came to the jug filled with milk, scooped it with a silver bowl and sprinkled it in the direction of Chomchook (the place where the relics were kept permanently). In Altan Debter (instructions on how to lead the ceremony), the ritual is stated as follows: “Khagan and jinon put a white stallion on the white felt; braid its mane, forelock and tail with nine by three white silk ribbons. Fill the golden vessel with mare’s milk, stick a jalma wrapped in sheep’s wool in front of it [a jalma here is birch branches used for the ceremony]. Bow before the heavens! Sprinkle from the nine silver bowls! Altan gadasu [the person symbolizing the sacral center of the ceremony, the “Golden pillar” or the Pole Star], don’t move!” (Zhamtsarano, 1961, p. 211).

With the beginning of the perestroika, sacred attributes associated with the figure of Chinggis Khan, began to be created in the Mongolian Republic as well.

After that, the mares and sheep were slaughtered; their meat was boiled and offered, together with wine, to Chinggis Khan and his wives, with prayers. Afterwards, the ceremonies of “sacrifices to the fire”, “consecration of the house” and “call for happiness” were held. During these rituals, they sprinkled koumiss over the fireplace and drank wine. The next step was to slaughter a sheep and boil its meat. The meat of the animals sacrificed was eaten; and the meat of the sacrificed mare was distributed among the guests according to their status.

Many nations of the Altaic language family including the Tuvinians, Kazakhs and Buryats claim to be related to the founder of the Great Mongol Empire.On the third day of the New Year, which is considered to be Chinggis Khan’s birthday, the rite of tasma (belt) used to be performed. The old belt that tied up the cushions with the holy objects (Chinggis Khan’s hair and shirt and his wife Borte’s dress) was cut into pieces and given to believers. The cushions were tied up with a new belt. At that time, “the Prayer of libation of the Lord’s sülde” was recited, where the master’s sülde (Chinggis Khan’s charisma) was named the deity of four or eight directions: “I sprinkle four times by nine to the deity of four corners [directions], I sprinkle eight times by nine to the deity of eight borders” (Rintchen, 1959, p. 86). And Chinggis Khan himself is described in the text as the sacral center harmonizing the space: “Chinggis Khan, who became the Lord of the world’s states, [whose] name is Temüjin-Bagatur, four precious wives, four mighty brothers, four tireless sons” (Ibid., p. 67).

A good horse has many masters

The president of the Republic of Tyva Sherig-Ool Oorzhak made the following comment on discussions about “the great Mongol being Tuvinian by birth and location of his grave on the territory of modern Tuva”: “If a person becomes a historical figure, he, like a good horse, gets many masters. <…> As regards the close relationship between the Tuvinian and Mongolian civilizations, it is indisputable. Tuvinian language belongs to the Turkic group of languages. Together with Mongolian tribes they formed the great Turkic civilization.” (the Internet magazine Eurasian review).The Kazakhs keep up with the Tuvinians: “According to official data, Chinggis Khan (whose real name is Temüjin) was born on the territory of modern Mongolia. <…> in 1155 in the clan of kiyats. <…> In 1206, during the kurultay (a meeting of clans’ rulers) Temüjin was announced a Khan and got a new name <…> And taking into consideration the fact that participants of the kurultay were the Kazakh clans of kiyats, merkits, zhalair and argyn, the scholars argue that Chinggis Khan was a Kazakh…” (Zhumagulov, 2003, p. 5).

The author suggests his explanation to the situation: “Kazakhstan, young as a state, during the 13 years of independency did not fill in the ideological niche. This is why the figure of Chinggis Khan is highly important: it can “lay the foundation” of Eurasian culture. <…> In other words, while Mongolians are peacefully shepherding their flocks and waiting for the day of the sacred anniversary, their enterprising neighbors are busy with a fundamental change of historical facts” (Ibid).

Is it a surprise then that an article with the meaningful title “Chinggis Khan was a Buryat” was published? The researchers quoted contend that Chinggis Khan was born in the Deliun Boldok area of the Aga region among the Buryats, or Khori Mongols, who had been wandering along the banks of the Onon River since the old times (А. Makhachkeev, Informpo¬lis newspaper of 10.15.2003, Ulan-Ude). It is true that a number of sacred places are found in the Aga steppes which the local inhabitants connect to the name of Chinggis Khan and that there are legends and stories about him.

Chinggis Khan’s sülde is a symbol of the nation’s unity

From Middle Ages to the 90s of the 20th century the Mongolian identity was symbolized only by the complex Edzhen Khoro in China, as the sacred relics of Chinggis Khan were kept there (yurts, banners, arms, clothing, etc.). However, with the beginning of the perestroika, the sacral attributes associated with the Founding Father began to arise in the Mongolian Republic, too. Thus, in 1991 in Khentey, where Chinggis Khan was born and presumably buried, a stele was installed, and the traditional worshipping ritual was performed.

The memorial in the ruler’s homeland was inaugurated to counterbalance the complex in Edzhen Khoro. The ceremony attended by thousands of Mongolians and many foreigners included numerous celebrations: various performances and the naadam (“three men’s games” — horse race, wrestling and archery), which is an entertainment and a ritual combined.

Today the banners of Chinggis Khan — traditional sacred symbols of the Mongolians — are kept in the Palace of Government and in the Ministry of Defense of the Mongolian Republic.

Another act of creation of a sacred center for the new post-socialist Mongolia was reconstruction of Chinggis Khan’s banners — Khara sülde (Black banner) with four bunchuks and Tsagaan sülde (White banner) with eight bunchuks. Today these containers of Chinggis Khan’s charisma are objects of worship and symbols of unity of the Mongolian nation. Each bunchuk is a pike on top of which a ring with horse hair buns is fixed. The unity of the nation is symbolized by the hair gathered from manes and horse-tails from all over ¬Mongolia for the Black banner, and from a thousand of horses for the White banner. The stone on which the White banner is fixed is also sacred as it was brought from the ancient Mongol capital Kharakhorum. Staffs of the banners made from the pine-tree that grew in Chinggis Khan’s homeland in Khentey are also sacral.

The White banner is kept in the Palace of Government of the Mongolian Republic; the Black banner is in the Ministry of Defense. Worshipping the banners, traditional sacred symbols, is becoming a component of the modern state ritualism: government members as well as the President have been participating in these ceremonies.

Characteristic of modern ethnic ideology is appearance, in the process of national cultural revival, of a new interpretation of the past and development of a system of mythologemes/ideologemes corresponding to the new tasks. Understandably, such mythologemes as “the great state of the past” and “the culture hero” represented by a real historical person play a central role. In this context, the personality of Chinggis Khan gets special attention not only among Mongolians but also among other nations of the Altaic language family (Tuvinians, Kazakhs, Buryats and others) as it remains the sacral center around which national intellectual elites draw borders of their ethnic communities — and furthermore, communities of the vast Eurasian expanse.

Chinggis Khan’s anniversary was celebrated with more than 60 events in Mongolia alone. They included concerts involving hundreds of people and huge cavalry shows in Middle Ages period clothing. Even professional researchers sometimes fall a prey to the excitement of the last years, announcing the creator of the Great Empire “the Father” of democratic features in the traditional political culture of Mongolians (Sabloff, 2002). However, “…how can Chinggis Khan simultaneously represent a symbol of Mongolian traditional democracy for Mongolian democrats and the embodiment of the authoritarian tradition for those who call to its implementation in the current market environment?” (March, 2003, p. 65).

Time will show if this racket about the legendary man who died about 800 years ago was only caused by the widely celebrated anniversary. However, these disputes along with a great number of research studies and works of art devoted to the one who “shook the Universe”, is just another argument in favor of his immortality in the memory and deeds of his distant descendants.

References

- P. B. Baldanzhapov Altan Tovchee. 17th century Mongolian Chronicles. Ulan-Ude, 1970.

- Ts. Zhamtsarano. Chinggis’s Cult in Ordos: From the journey to Southern Mongolia in 1910 — CAJ. 1961, t. 6, № 3.

- Loubsan Danzan. Altan tobchee (Golden Legend). Мoscow, 1973.

- A. March. Citizen Chinggis? On explaining Mongolian democracy through “political culture” // Central Asia survey, Vol. 22, 2003, No 1.

- P. Sabloff. Why Mongolia? The political culture of an emerging democracy // Central Asia survey, Vol. 21, 2002, No 1.

The authors and editors thank the scholar of Mongol studies I. Shimamura (University of the Shiga prefecture, Japan) for the kindly shared photos.