The Arbiters of Eon

“If you’re not interested in archaeology, it doesn’t mean that archaeology won’t someday be interested in you,” once wrote on my bathroom’s wall a man whose school nickname Archaeologist would become his profession

Between ethics and aesthetics. Above the sea level, so to speak

Raimbek is a hospitable man, but he doesn’t talk much. Why should he? To feel a person, you don’t need to jabber. If you happen to be Raimbek’s guest, you shouldn’t think your host is so taciturn because you’ve done something wrong. If someone doesn’t talk to you, it doesn’t mean they don’t feel you or aren’t happy to see you. And the other way round. We, the denizens of large cities, have become so used to the never-ending how-are-you and what’s up as well as to the fact that everyone couldn’t care less about how we truly are. But here it’s all clear how. If you’re alive – you’re doing great, so why babble? Idle chatter is nothing but a snag for true feelings.

Once we called on Raimbek and drank tea in silence. It was only when the long-awaited drone of a helicopter roared in the distance that Raimbek decided: this occasion was worth a word of mouth. He paused for a second and uttered, laconic as an Indian, “Now!”

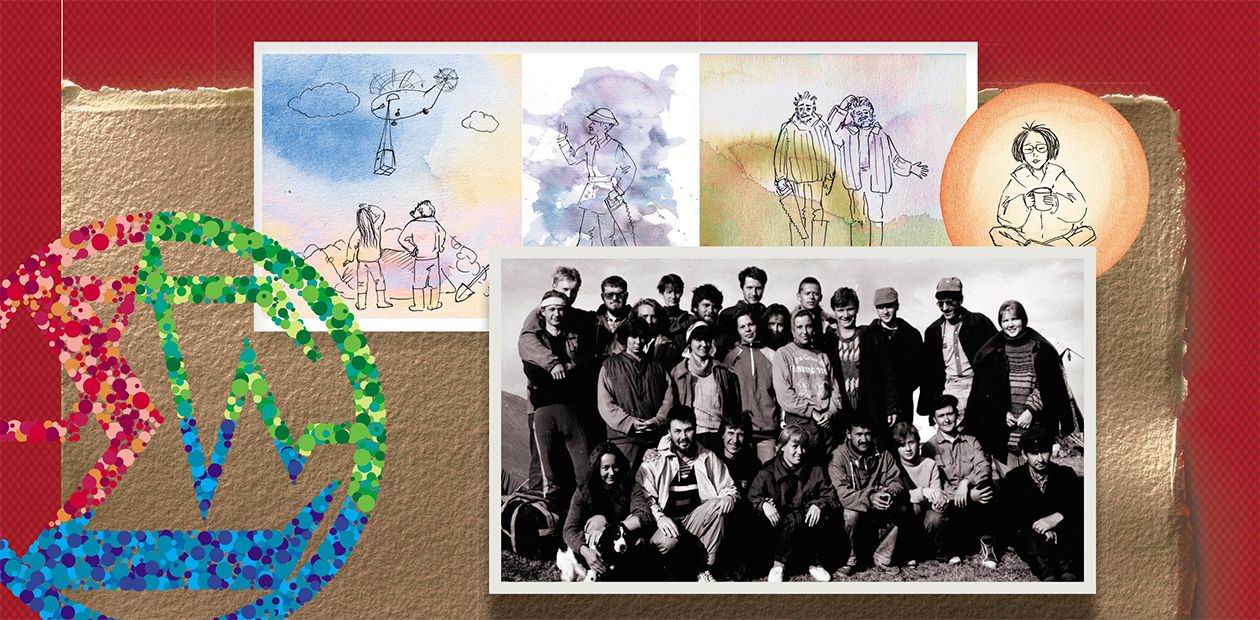

The helicopter brought the main squad of archaeologists, for whom we, the leading party landed on the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Mountains a month ago, had grown impatient of waiting.

What – you’ve heard nothing about the Ukok Plateau? About the tattooed Scythian horsemen, remarkably well preserved in permafrost? About their beloved beasts – the numinous griffons – an ornament that they put on everything worth decorating? About the real griffons that sometimes fly over to Ukok from the neighboring Mongolia? About the Ak-Alakha River, whose water is like milk? About the sunsets projecting gods’ dreams on snow-capped peaks? Then I do envy you: the “hard drive” of your subconscious mind has still a lot of space.

In truth, archaeologists had long known about Ukok, but they began to dig there systematically only in 1990, when an expedition from Novosibirsk excavated the first mound to discover a double grave of Scythian warriors. Their bodies did not survive, only the skeletons. But the garments, the felts, the quiver – all these finds were in excellent condition.

This culture, called the Pazyryks – after its first place of discovery – stands out for its remarkably well-preserved organics. All thanks to the Scythians, tough guys, who dug three-meter-deep graves in permafrost and banked over them colossal mounds of rocks and boulders. Since they did all this high up in the mountains, ground- and rainwater that filled the burial chamber did not melt during summer: everything that froze there froze forever.

Apart from permafrost, other factors contributed to the outstanding preservation of the mound: the acid–base balance of the soil; the time of the burial; intrusions of robbers, not only the so-called tomb-raiders of modern days but also ancient grave robbers, driven by mystical, rather than mercenary, motives.

Finding a mound with an optimal combination of all these factors is a big try. More truly – no matter how hard you try, you won’t find one because this kind of luck can only be granted by spirits willing to unearth a long-hidden secret. This is the metaphysics of archaeology according to a well-known Siberian shaman Bair Richinov.

Ethical issues, relating to metaphysics, are our constant source of worry. Is grave-digging ethical in relation to those gone to the next world, or they don’t care? Do excavations bring harmony between that world and this one? Or strike a discord? Is scientific search a legitimate cause for curiosity? Won’t our thirst for knowledge about this world bounce back at us in the next one?

Material things exist in space; their mental images exist in time. Forgotten things do not exist. Creators and owners of things disappear together with their creations and belongings. Archaeologists do not simply grub the ground – they breach through time, unearthing ancient things, those material clots of world-culture history, and patch holes in the walls of our world. Archaeologists – the arbiters of Chronos and Topos, the priests of Clio and Urania – recover the ideas about the world that are materialized in things, pulling them out of oblivion.

Therefore, the metaphysics of archaeology is the sole purpose of its geek participants – such rare yet ‘do-it-all’ workers as a senior laboratory assistant. So, to dig or not to dig? That is the question. But not to us or to the skull of another “poor Yorick,” whose yellow bone has emerged from under the shovel.

Here comes the world fame

When our boss Natalia Polosmak, back then a PhD at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk, decided to excavate the mound, that would soon make history, a well-known archaeologist, professor Vyacheslav Molodin, who also happened to be her husband, said, word for word, “Normal mounds aren’t enough for you?” A scientist demonstrated scientific skepticism. However, archaeology, the most materialistic of all sciences, hinges on one nonmaterial circumstance – Fate. From Fate’s point of view, Natasha, who had learned to trust her intuition, saw it better. And the ordinary, totally unremarkable mound was excavated.

We opened the burial chamber – a larch vault. Inside we saw pure ice, white, in sign of our pure thoughts, totally opaque. So we thought: No celebration yet. Anything could be inside. As well as absolutely nothing. Robbers might have rummaged the grave before the ice formed, filling an empty vault.

A week went by with us sitting on ice in a pit, then another week… We tried to melt the ice, we poured hot water on it, but the frozen monolith didn’t seem to end. The spirit of scientific skepticism electrified the atmosphere so one could charge batteries in this air.

“O-o-oh, it’s all so bad! We’ll find nothing but ice!” moaned Lena Shumakova, the world’s best archaeological artist.

“A-a-ah, what will I write in my report?” our boss repeated worriedly.

“U-u-uh, we’re all gonna die!” screamed Ira Oktyabr’skaya, the great ethnologist of Asian peoples, when she saw me cut bread with a knife I used to poke ice in the grave.

“All systems have an end,” I snapped back, wiping the knife on my insect-protection suit, which I, by the way, didn’t change after work since I only had one.

Ira rushed out to vomit, while we continued our lunch, exercising in grave humor.

Episodes and characters

We didn’t have any communications. Neither did we want to. It was a mythological era, when satellite phones weighed and cost like satellites, and mobile phones weren’t something regular folks would normally have. So we, like many of those who found themselves in similar circumstances, lived in the reality of most primitive communications and sent word to the world by means of couriers, messenger pigeons, and visiting academics. But somehow this was enough for rumors about our find to spread even before it finally thawed.

Those in the big world knew what we found here and were highly sympathetic, helping us in every way they could. They sent us parcels with items they thought were indispensable. We were doing just fine when, all of a sudden, a helicopter unloaded a big box full of gas masks with a cheer-up note that could make the spirits weep.

“What the hell?!” was the group’s response.

“Could this be about the ancient bacteria?”

“U-u-uh, we’re all gonna die!” Ira blubbered and whisked away.

Hardly had we sent the gas masks back, with our thanks, another helicopter brought us a fridge, a big new Stinol.

“And what the heck is this for?”

“To freeze the bacteria?”

“Maybe to keep the mummy?”

“But there are shelves inside!”

“We can break the shelves.”

“Why break a good thing?”

“Okay, but where are we supposed to switch it in?…”

So the fridge flew back too. In return, we received a live medical man.

Ooh-la-la!—a radiant, fashionably dressed dandy fluttered out of the helicopter. He introduced himself as an urologist and made a dirty joke.

“Another intrasocial monster,” Dimka aka Archaeologist muttered disapprovingly about the urologist. He was generally disapproving of urologists.

However, the doctor soon flew away, once he realized that we didn’t need him. As a farewell gesture, he made an appearance at the excavation site and declared that the “patient,” i. e., the mummy of a young woman, had suffered from lepra, when still alive.

Don’t know about the others, but I was head over heels with joy. Hurrah! We were all gonna go to a leprosarium! For such an occasion, I put on a raincoat of vibrant green color, made a bell from a tin can and fastened it to my leg. Adorned like that, I came up to Ira:

“Ira! Our ‘client’ had lepra. We’re all gonna die. So let’s now kiss!”

Then arrived another fancy Dan. He emerged from the helicopter, exquisitely dressed in a safari suit, looking like a beau from a men’s magazine. “Hi,” he said. Okay, hi yourself. And who the heck are you?

The fancy Dan turned out to be a Matthias from Zürich, a dendrochronologist. He got wind of the ancient logs, sharpened his saw and rushed up here.

To be fair, a week later all that remained glossy about this guy was his Hasselblad, his other glamor gone with the wind, like pollen. All because Matthias was a right guy, open to assimilation.

We are standing on the lake shore, like three Alyonushkas from the Russian fairy-tale, pondering over the unfair distribution of substance in nature. So much water, and nothing to dissolve it with. Near stands Matthias, with a week’s growth on his jaw and sacks under his eyes. Dressed in a most indigenous undershirt and kirza boots. His eyes are full of sorrow. So much water not dissolved with alcohol…

“Matthias,” drones pensively Shura Pavlov, a scourge for computer monsters and an ex-deputy-dean of the Department of Law at Novosibirsk State University,“… you… are… You’re looks like Russian… Russian alcoholic.”

“Cha-a-arma-a-ant, <…>” drawls Matthias, just as pensively.

We all keep gazing at the water…

One more episode.

“Hey you, string the tent!”

“Let’s drink! Razlivai!”

“Arigato gozaimasu,” responded a Japanese girl Tei Hatakeyama-san from the Tokyo Museum of Literature to a half-cup of almost pure alcohol, only slightly dissolved with water, and began to sip it like sake, gripping the cup with both her little hands.

Hatakeyama-san was, essentially, 32 kilos of biomass, together with her glasses and mountain boots. But a drop of alcohol didn’t kill a mouse. Even Anton Luchansky, a famous musician and TV reporter, had exorcised the demons from the tent and threw out the oil stoves, but Tei kept sitting, like a netsuke, smiled and chanted, “Arigato gozaimasu.”

“O-oh, she is a true daughter of a samurai!” uttered Archaeologist, magnificent in his brutal machismo, and patted the little lady on the back.

More truly, he was about to pat her… The girl dropped on all four and crawled out of the tent, pattering “Hazukashii,” which could be translated from Japanese in this context as “Sick! I’m sick!”

By morning, all of us were hazukashii. But the Japanese Thumbelina, having recalled whose daughter she was, gathered all her willpower and made it first to the excavation site.

Grave for National Geographic

One day, the smell of the thawed organics, promising a sensation, dragged the team of National Geographic Television. We could smell that someone extraordinary was flying from the way the helicopter was cruising the air, making aerobatic stunts. We saw an open access door and a cameraman in white pants and jackboots, taking a shot.

“Kill you all,” muttered the officer Vovka from the frontier post, who had raced up on a pregnant mare.

“Welcome, dear colleagues,” the translator rendered Vovka’s words in a politically correct way.

Together with the television team, the helicopter brought people from the National Geographic magazine – a photographer and a writer. The entire herd set up a camp at the excavation site, not to miss a thing. Even before the start of a working day, one of producers would roam near the mound, soon followed by the rest of the team. All of them longed for “action” because, from a filmmaker’s point of view, the monotonous archaeological process always lacked something, be it dramatism, optimism, pessimism, mysticism, sado-maso-eroticism, or other sorts of dynamism.

One pastoral morning, they had it all. That morning began in a most ordinary way, with the drowsy scooping of water that drenched into the pit from the thawing permafrost. Exactly when we dipped out the last drop of water, the southern wall of the grave crashed. Those who know something about the structure of Scythian mounds should now freeze in anticipation of a dramatic denouement because this crash meant that the wall could have well crushed on the mummy. And it would have if our squad hadn’t been prepared for any mishap. The wooden block with the mummy had been shielded with large wooden sheets, which caved in under a tonne of pebbles.

An ethereal projection of the NG producer was fading at the edge of the pit, he himself rushing at full speed towards the camp to summon his team. Soon the whole world would know that the pit wall had crashed on our watch.

“Hazukashii, idiots! Get out the ground!” shouted someone in our group.

At the horizon, shrouded in a cloud of dust, the entire television team was rushing towards us. Rich, the cameraman, was hastily chewing his sandwich and adjusting the white balance in his camera. Ralph, the sound engineer, was putting on his earphones with one hand, attaching a fluffy mouthpiece to a stick with his other hand and tying his shoelaces with a third one. The light directors and assistants were unfolding reflector screens. The producers helped and spurred them in every way.

“Hurry up, guys!”

They were approaching, and our shovels whirled like fan blades. If an independent expert from an anomalies committee had happened to be there, they would have discovered that the teleportation of a cubic meter of ground to a distance of a dozen meters was possible. It’s pity that it was the filmmakers from National Geographic that witnessed the teleportation phenomenon. When they finally hovered over the pit, they could only shoot a brush gently sweeping the logs in a most pastoral way.

Last adventure of the biological structures

The withdrawn bodies and objects, which had spent in ice 2,500 years, were to be preserved for future generations in the same form as they were discovered, or even better. We, senior laboratory assistants with the archaeological squad in summer and men of various professions in winter, descended from the mountains and returned to our urban life; however, our friends-archaeologists had no time to waste. All the items awaited top-notch restoration. For a year, the restorers saturated the vault logs and wooden blocks with polyethyleneglycol-based substances to make them imperishable. And the heroes of the day – the mummies – went to Moscow for final conservation at the Institute of Biological Structures, whose main “client” has been and still is some guy named Vladimir Lenin.

The restoration is as costly as it is unique, but it’s worth the cost. Only the scientists of this institute, not the priests of Ancient Egypt, can embalm a body precisely as it is, without turning into a resin cocoon and even without deforming the intravital volume of tissue. Consider Lenin, for instance, whose freshness and flourishing complexion is a constant source of vituperation: he has been on display in open air for 90 years and still as good as new – a triumph of matter over mind.

One day, the author of these lines had an honor to collect the body of a Scythian warrior in Moscow and escort it to Siberia, i. e., return to the lesser motherland. There were five of us because the man was portly and two meters tall; however, one would suffice to carry him: all his tissues were dehydrated and each cell was saturated with a preserving agent. After a year in secret tinctures, the embalmed skin felt like polyethylene.

However, I still remember the soft cold palm of the anatomic pathologist when we shook hands at parting at the platform of the Yaroslavsky railway station. Although his hand didn’t smell of the Styx sludge or the Cerberus hound, it still felt like a hand of Charon, accustomed to greetings and departures.

References

Bannikov, K.L. People of the Ukok Plateau. From the field journal of the 2004—2006 ethnography expedition // Polevye issledovania institute etnologii i antropologii. 2005 god (Field Studies of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, 2005) / Ed. by Z.P. Sokolova. Moscow: Nauka, 2007, pp. 278—292 [in Russian].

Bannikov, K.L. Spiritual notions of shepherds on the Ukok Plateau // Sotsial’naya real’nost’, 2008, N 5, pp. 22—35 [in Russian].

Bannkov, K.L. Faktor prostranstva: narody i kul’tury. Etnograficheskie etyudy (The Factor of Space: Peoples and Cultures. Ethnographic Sketches), Moscow: Madia-Bazar, 2008 [in Russian].