The Ukok diary

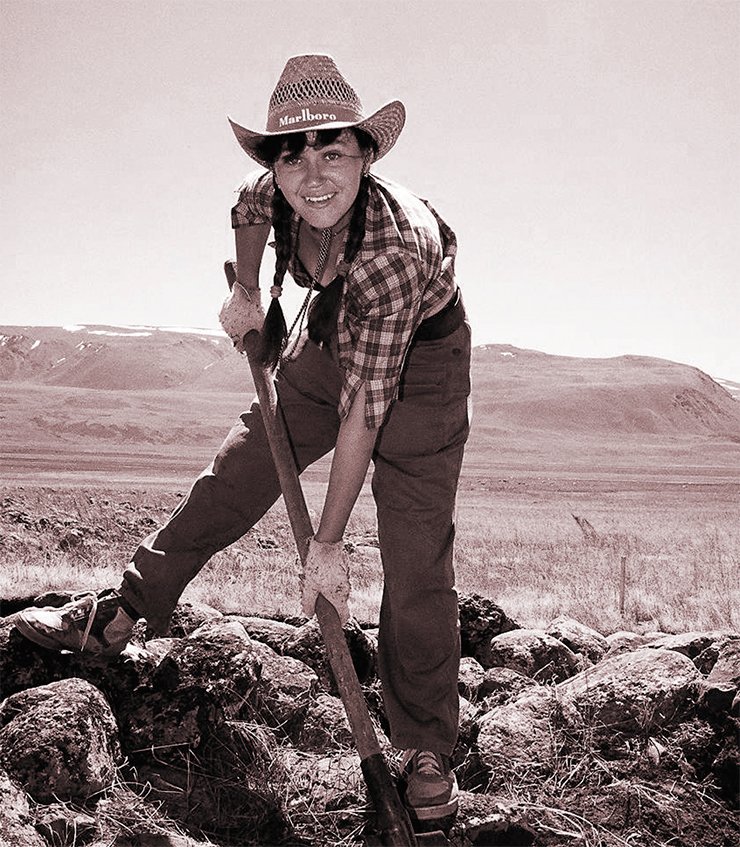

In 2004, the State Prize for Science and Technology was awarded to Doctor of History Natalia V. Polosmak and Academician Viacheslav I. Molodin, both affiliated with the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SB RAS, for their discovery and investigation of the unique Pazyryk monuments dated 4th-3rd cc. BC on the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Mountains. Found at the intact “frozen” burial site was a woman’s tomb with a remarkably well- preserved woman mummy and rich mortuary inventory

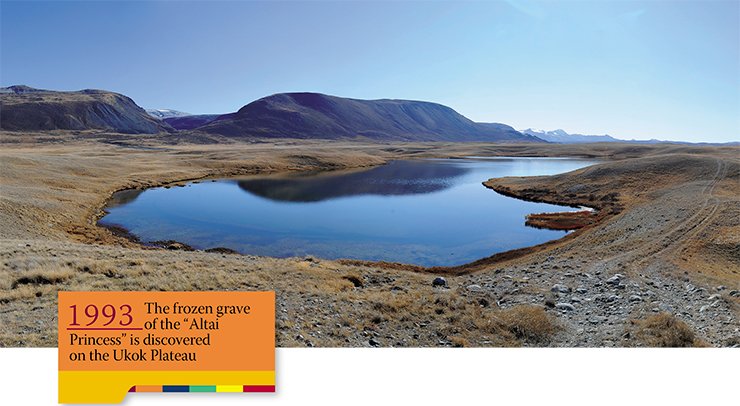

With each successive thawed layer of the ice tomb, the time was going backwards taking us further and further away from the modern age. Ukok contributed to this feeling through its solitude, aloofness from everything that was important on the mainland and strange, Indian-like names of mountains, rivers and settlements: Ak-Alakha, Chindagatuy, Bertek, Moinak…The silence around us was pristine, disturbed only by the remote drone of the engine at the frontier post. At night everything froze: the lake had an ice skin, small flowers and grass blades were covered with ice… With sunrise, however, everything went back to life. This daily return of life after the night’s cold was a stunning feature of Ukok!

The taste of rhubarb jam

I understood just recently why it is so difficult for me to recall that time: it appears that I can hardly remember any events. Evidently, something did happen in the camp: people would come and go, every day we ate something, slept some time and talked to somebody. Nevertheless, it did not go deep or left any trace in the memory; rather, it seemed a vexing distraction from the main thing that commanded full attention. When they tell me something about the events of those years, I can recollect that, indeed, there was a helicopter that brought us a fridge and gas masks and then took them back. Also, a doctor with a ludicrous (given the situation) specialization flew in, and some other amusing things happened, which now touch me deeply because I understand that it was because people cared about us, worried about us and wanted to save us God knows from what.

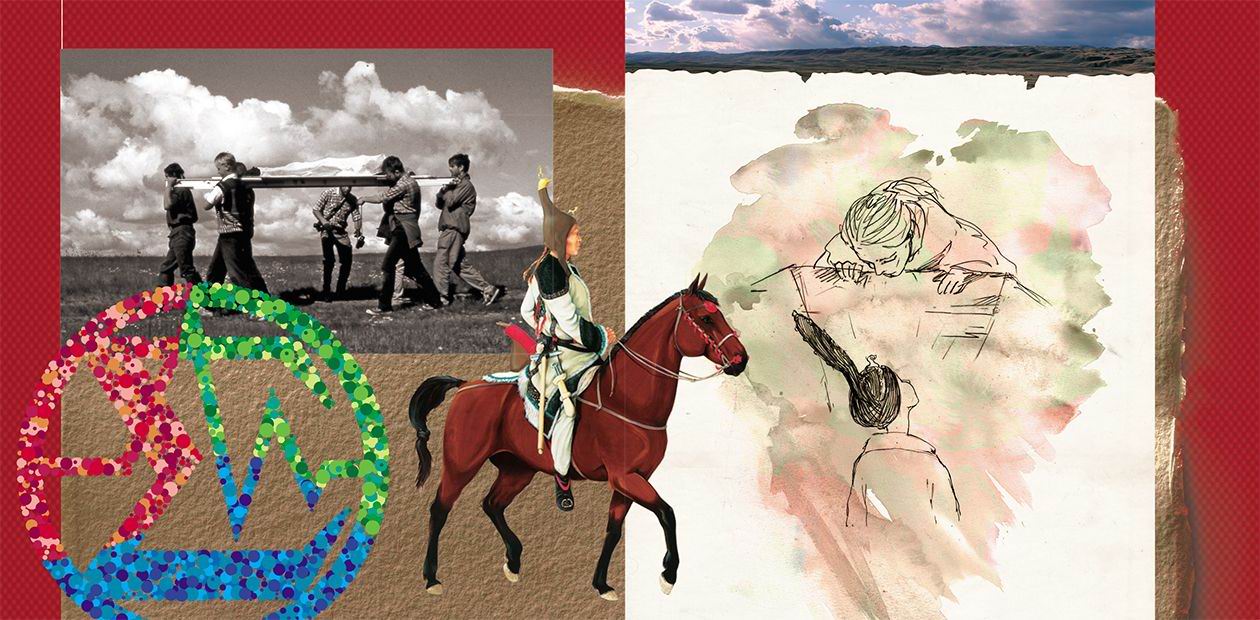

“I was lucky: I happened to be in Ukok when I was an undergraduate, during our field-period on archaeology. As I recall it, everything about this expedition was a surprising adventure and luck: our start from the Open-Air Museum in Akademgorodok, the first helicopter trip in my life, the amazing scenery of highlands... A true archaeological party and its head – a young good-looking woman, rigorous academic research and camp life, Scythian kurgans and a camera crew of NHK, a Japanese television broadcasting company. In my school day, after the lessons of the history of Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece, I decided that I would be an archaeologist and was even going to join an archaeology study group. Shortly, however, I switched to something else and forgot all about my dream until I happened to come to Ukok.

After the Ukok excavations, it was impossible to leave behind archaeological expeditions. Several years in a row, having taken the exams beforehand, our united expedition party would board a helicopter and go deep in the mountains to take part in unique archaeological excavations. The end of the field season was an unpleasant surprise; all we could do was wait for the spring to come suddenly to Natalia Viktorovna with the habitual question: “When are we off?”

And who could know what should have been done in that situation? We were the first. Of course, there had been S. I. Rudenko, who had dug the “frozen” Pazyryk graves in the early 1960s, but ours was a different time with different resources…And the main resource was the helicopter. I wish to sing praise to it and its pilots who would come to us over the high snowy mountains, with or without loads, in the bad and very bad weather, and we would always wait for them because they were our connection with the mainland that appeared to be so far away. It seemed as if we were on an island lost in the ocean, and sometimes the waves would wash ashore bread, tins and letters, and one day they even cast ashore gas masks and a fridge.

The events occurring around us and related to the routine camp life (if the word “routine” may apply here) had no impact at all on what was happening in the interior of the burial pit – every minute of our existence belonged to it, and it was the pulse of my life. Looking back now, I realize that this immersion into my own feelings and experiences was within an inch of a trance, when the world shrunk to the ice lens at the bottom of the grave. In the meanwhile, the camp lived its own life: entertained guests and celebrated birthdays, went on outings to pick up rhubarb and make rhubarb jam, Ukok’s longed-for delicacy.

The composition of our party formed in an inexplicable fashion and seemed phantasmagoric, too. Again, this was the spirit of the times; it reflected the surrealistic situation of that summer in Ukok and was a projection of the strange turns of fate that occurred in the lives of many participants of these events.

What brought Genny from Harvard University there and why did she take root in our camp? It escapes me. This lady astounded us when she picked up in her arms our biggest fellow, Pchela (nickname for his surname “Pchelintsev”), spun round with him and carefully put him down on the ground. Funnily, after this incident he sank in our eyes and no longer seemed as macho. She could catch logs with unfaltering hand and was up to reining up a horse if she felt like it.

“For me, as well as for many of my fellow historians, Ukok became an unforgettable emotional experience that can never be repeated. Not only because we became older but for lots of other reasons, too.

When in the very beginning of the 1990s we came to the Kosh-Agach district, we plunged into the atmosphere of a true scientific inquiry. Adding to the bunch of vivid impressions were the pristine nature of the uplands, Spartan conditions and a glimpse into the local traditional culture.

The summer of 1993 was one of the strongest impressions of my youth. That year, my good friend Kirill Lugov and I were getting to Ukok on our own. It was an adventure full of intriguing twists, meetings and happenchance. When we finally got to the camp in the frontier guards’ car, everybody was agog as they anticipated a big discovery, even a sensation: the archaeologists had hit an ice lens in a regular burial mound. And a sensation it was – for a couple of months, the plateau lost at the crossroads of four borders became a site that attracted experts of different fields and journalists from all over the world. As for us, we were happy to feel part of an important investigation.

This is how the Scythian mummy became a fact of my biography and archaeology turned into a life-long passion. Even after I went to television, I continued going on expeditions, though in a new quality. Now my task is to tell viewers about archaeology, a challenging but fascinating occupation.”

There was wonderful Frau Gerda, a very nice German woman with an amazing vibe of an eighteen-year-old girl. She had come to Altai as a tourist and was bogged in our camp. She got stuck in all our routines. No other frau would have stayed: she fitted in thanks to her outstanding personality. She always tried to be useful in that way or another, either by cooking something very German or by cleaning the bones of the Pazyryk horses extracted from the tomb. At night, she would stay by the fire “until the last customer,” and at the farewell party volunteered to act the part of the mummy – or the Lady, as she called her – rolled in a sleeping bag, she gave us a truly creepy show as she popped out darkness. I wonder where she is now, after so many years. In Germany, people live long and I do hope she is still fine.

We did have a great team, very friendly and tight-knit. One day, a Japanese girl, Tei Hatakeyama, appeared in our camp, brought either by helicopter or by the wind – so tiny and zephyrian she was. Just came out of thin air, and that was it. “A mirror image of a netsuke,” commented Kostya Bannikov with his love for everything Japanese (he was learning Japanese at the time). In Japan, Tei was a postgraduate studying animal style, if I remember it rightly. It did not matter though. In the camp, she never left the “frozen” grave. Whenever we lifted our eyes up from the bottom of the pit, we would always see not the sun but Tei’s little face and the just as interested snout of my spaniel Pete. Sometimes, they could not take it any longer and fell down into the pit. Pete would just jump down, having had enough of being just an observer, and Tei would very politely plead to please go down to maybe help in some way and touch that ancient ice. Having received the go-ahead, she would climb down and stand reverently by in her sopping wet canvas shoes.

Then, there was Karla. If you ask me how this German undergraduate came to us and why she stayed, I cannot answer. People used to materialize and walk through our life like shadows but some of them stayed in flesh and blood. They were accepted for some reasons unclear either to them or to us and thus became part of the Ukok family. This was the case with that German girl – she stayed, and we still keep her detailed drawings of the horse harness found in the mound.

“During our first season Ukok seemed to be another planet, huge and unexplored. We had a haunting feeling of an alien presence, of being watched. I think it was partly because there were so few of us on that immense “serving plate” – the mountainous plateau with nothing but stars above it. The border guards, with their sudden apparition and just as surreal vanishing in the local scenery and the beam of the searchlight going along the barbwire contributed to the mysteriousness and made us think of the Zone from Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky.

I was deeply impressed when, having placed the clothes and fragments of clothes lifted up from the tomb into photo cuvettes, we (Natalia Polosmak and the author –Ed.) rinsed them in the water of the nearby lake to get rid of the marks of decay. In fact, we just did some washing for a person who had lived a couple of millennia before us. Could that person (or we) imagine such a thing happening? The time reduced to nothing, and millennia became an instant.

For a long time, this story remained my “inner experience”: anticipating the restorers’ displeasure, we kept it to ourselves. One day, however, having mentioned this episode in Abegg-Stiftung, a well-known restoration center in Switzerland, I received surprising support. It turned out that it was the water of the glacier lakes of the plateau that had preserved and “brought” to our days the unique content of Ukok’s frozen burials.”

Matthias Seifert was an invited dendrochronologist. God knows what he had been expecting when he was flying in, but it looked like the reality disagreed with his expectations. For a Swiss guy, mountains and glaciers were old hat but Ukok had something that stirred the blood and made the months spent there the best ever lived. When Matthias, who had taken on the look of a regular village guy, was flying out, he was crying. Though everybody promised that we would definitely see him again, we all understood that it would be very different. We did meet, but that was a different life and different meetings.

Matthias did a great research into the dendrochronology of the Ukok kurgans. Thanks to him, our research institute has its own dendrochronologist, Igor Sliusarenko. Having seen Matthias at work, Igor could not resist it. He realized that his calling was not ceramics he had been involved with but that fresh wood. Today, he has been working with it for almost quarter of a century.

At that time, many things changed, both in our lives and in our ideas about the job, archaeology. The archaeology was different, both technically and emotionally. We were saturated with the “grave smell,” the tenacious smell of the organics that had been decaying for over two millennia and had been purified by ages. It was the smell of the wet clothes on the interred woman, the odor of the wood of the tomb chamber and log coffin; it was the aroma of the bygone world. We lived in two dimensions: in the Pazyryk world that shrank to the five by three meter pit and in the modern world, our camp. The ancient world seemed much closer and more real than the modern one, an unwanted break before the everyday return to the enchanting and unpredictable past.

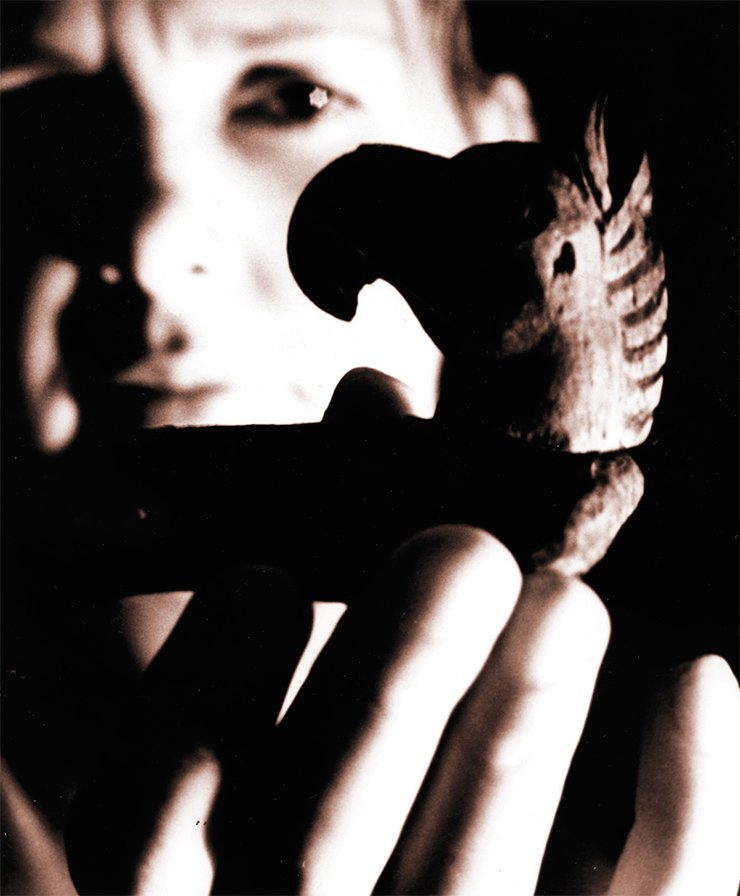

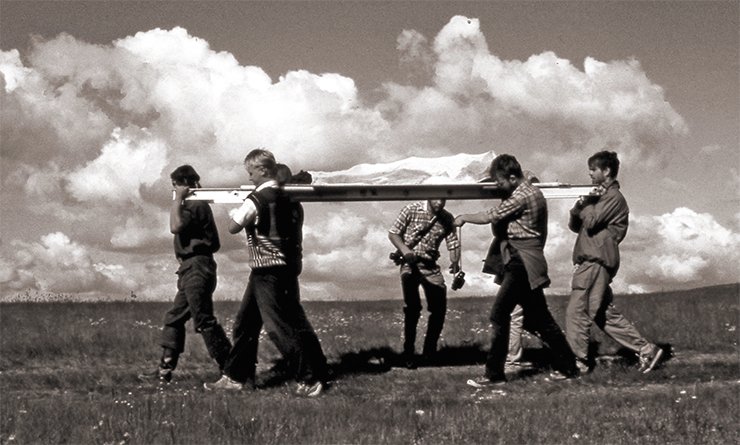

The saddest day was the day when we lifted the woman mummy from the log coffin and carried her on the custom-built stretcher to a small house in the camp, where she had to “wait” for the helicopter that would take her to Novosibirsk. That was the end of the first part of this story – and the second part has spanned more than twenty years and seems to have no end in sight.

A friend of mine, an ethnographer from Altai, said, “If She had not wanted it, you would have never found Her.” I agree. But if She had wanted it, what for? I have been thinking about it all these years and I am sure it was not for that hysterical campaign that we have been witnessing in Altai. No, that would be too trivial. She has come to tell us something important for us, and our task is to understand how we can hear this story about herself, her culture and her time.

In fact, this is what we have been doing for almost 25 years: we have been “listening” to her story. If we accept that life does not end with physical death, we can say that her destiny is fortunate. After more than two thousand years of oblivion, she has become the life-breath of writers and artists; films are made about her, fashion designers create collections based on her costume; dozens of people throughout the world copy her tattoos; a new mythology has developed around her…In fact, we gave her a second life. This may be the meaning of her apparition in a frozen grave on the Ukok Plateau…History needs personalities. When we talk about those unspeakably remote times with no names, for lack of something specific we have to resort to such concepts as “archaeological culture,” historical “community,” and so on. Then, the apparition of a concrete person from there becomes a miracle that breaks our abstract notions expressed in terms, making those times part of the continuous life, in which we so far are the last, they used to be the last, and soon somebody else will be the last.

References

Polosmak N. V. The Riders of Ukok. Novosibirsk: Infolio-press, 2001. 334 p. [In Russian]

Rudenko S. I. The Culture of the Altai Mountains Population in the Scythian Times. Moscow; Leningrad, 1953. 401 p. [In Russian]

Molodin V. I., Polosmak N. V., Chikisheva T. A., et al. The Phenomenon of Altai Mummies. Novosibirsk: Publisher of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SB RAS, 2000. 318 p. [In Russian]

Polosmak N. V., Barkova L. L. The Costume and Textiles of the Altai Pazyryks (IV—III cc. B.C.). Novosibirsk: INFOLIO, 2005. 232 p. [In Russian]

Pilipenko A. S., Trapezov R. O., Polosmak N.V. Molecular-genetic analysis of human remains form Ak-Alakha 3 Tumulus 1 // Archaeology, Ethnography and Anthropology of Eurasia. 2015. Vol. 43. № 2. P. 138—145.