Behind a "Shot" of Archaeological Sensations

In issue 12 of our journal, Doctor of History Natalia Polosmak and Candidate of History Evgeny Bogdanov dwelt on the unique findings discovered by the Siberian archaeologists at the diggings of a Xiongnu burial-mound in the Noin-Uly mountains, Northern Mongolia, in 2006. The current issue offers a joint publication by experts from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS), who focus on the scrupulous work restorers do to give the artifacts a second life

What threadbare silks! What ancient garments!

We cherish a faint hope that there is life in them

As long as our hands can touch them

And we can discern a faded pattern of dragons

Who have lived in China from the times bygone

Many people believe that what they see in museums is the way the artifacts looked when they were found in ancient burial grounds and settlements, and only few have a true idea of what these things used to look when they were dug out. It happens very rarely that something that has been buried in the earth needs no restoration, though this may be the case with artifacts made of gold, stone or ceramics. As for all other things, it takes many efforts to make them assume their primary form.

In issue 12 of our journal Doctor of History Natalia V. Polosmak and Candidate of History Evgeny S. Bogdanov dwelt on the unique findings discovered by the Siberian archaeologists at the diggings of a Xiongnu burial-mound in the Noin-Uly mountains, Northern Mongolia, in 2006. The current issue offers a joint publication by experts from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS), who focus on the scrupulous work restorers do to give the artifacts a second lifeRestorer’s work is usually “off screen”, though only a skillful restoration can give a second life to an ancient thing and keep its new look for the centuries to come. No archaeologist having some respect for him/herself will start digging without being sure that everything he or she is going to find at the burial ground or settlement will be properly restored and preserved.

Beginning in 2006 our large project on investigating the burial mounds of the honorable Xiongnu, which are part of the Noin-Ula monument located in the mountains of Northern Mongolia, we had some idea of what we were going to find and were ready for the immediate preservation and subsequent restoration of the artifacts yet to be found. Wonderful about archaeology, however, is the unpredictable situations it sometimes offers. The conditions in which the ancient burial implements were found in the 20th Noin-Ula mound have ruined the conventional stereotypes. The double burial chamber made out of pine logs and set 18 meters deep was violated by ancient robbers who penetrated it through a hole cut in the ceiling. The chamber could not resist the pressure of many tons of puddled clay and stones that filled the burial pit and folded up like a house of cards. All the objects that were inside it suffered mechanical damage to a greater or lesser degree. Moreover, there was water inside the chamber, which helped to preserve things made of lacquer and textile—these have practically never reached us across the millennia. On the other hand, the water washed off and drew inside some of the fine light-gray clay and coal that the builders had put in layers between the walls of the burial chamber and burial pit. In the two thousand years that have passed since the burial took place, this viscous aggressive mass has covered and impregnated everything inside the chamber, all the things that accompanied the person buried in it, inflicting on them an irreparable damage.

“We, an expedition team from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SB RAS, have come to the Noin-Ula Mountains, a most picturesque ridge in northern Mongolia, to dig a burial ground of the Xiongnu —the first people to establish a nomadic empire, which is better known from Chinese chronicles than from archaeological findings.Ancient burials were discovered in the north of Mongolia in 1912. While the technician of a gold-mining company A.Ya. Ballod was making a bore-hole in a huge old pit grown with bushes and pine trees, he came across ancient weapons, gold artifacts, vessels, remains of silk fabrics, and many other things. It was thus that the Noin-Ula mounds, which later became world famous, were discovered. Regretfully, the turn Russian history took at that time put off their investigation for dozens of years.

A few of the mounds were re-discovered by the expedition led by the well-known traveler and scholar P. K. Kozlov as early as in 1924—1925. It was established that the mounds lost in peaceful valleys amid the forests contained remains of the Xiongnu top dignitaries. Diggings produced sensational results: works of the previously unknown animalistic art, fabrics from the Mediterranean and Central Asia, Chinese silks, felt carpets with applications made in the animalistic style…The artifacts turned out to be in great form thanks to the cold climate and clayey soils and were thus able to tell us not only about the Xiongnu but also about their contemporary civilizations of the West and East.” (The Past 18 meters Deep by N.V. Polosmak and E.S. Bogdanov. SCIENCE First Hand, 2006, 12, pp. 8—17)

The fabrics have suffered most. Fragments of carpets, curtains, and clothes were taken up from the burial chamber together with clay. In fact, these were lumps of clay with hardly visible traces of cloth. To make matters worse, it was October when we got to the chamber floor, and night frosts bound the wet clay and coal dust together with silver plates, copper buckles of horse harness, and fabrics. In the daytime, it was not much warmer, which made it impossible to work with the artifacts. We only managed to prepare them for transportation to Novosibirsk, and did out best to create the best possible environment for each category of artifacts so that they would survive the journey. For instance, lacquer and wood had to be placed in a moist environment while metal things had to stay dry. In this form, the artifacts were sent from Ulan-Bator to our research institute.

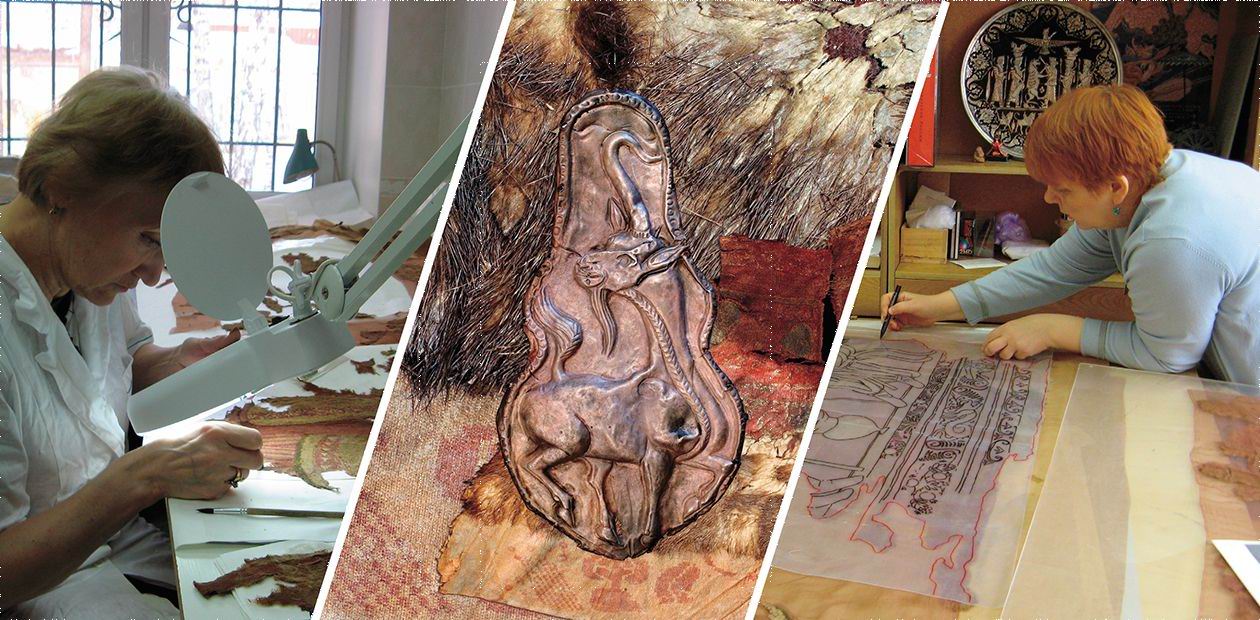

To dig an archaeological monument is only half of the battle. Preservation of the materials dug out, their perfect preservation, and further restoration—these are the tasks not many can cope with. In order to preserve the unique artifacts obtained in Mongolia, efforts of a team of highly qualified researchers—restorers were required. The Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography formed such a team when the Pazyryk monuments discovered in the Mountainous Altai were being investigated. It was then that the invaluable experience of dealing with fabrics and wet wood was acquired.

The present collection is extremely complicated to deal with because of the number of things it contains, their composition and condition. On top of this, some utterly new things have been found—lacquer artifacts, which we had never handled before. As we had to carry out massive highly-qualified work on the restoration of the unique and complicated things in very short terms (the collection has to be returned to Mongolia this fall, two years after the diggings took place), we applied for help to the leading Russian experts, world class restorers Natalia P. Sinitsina, State Research Institute of Restoration, and Vladimir G. Simonov, Grabar Russian Art and Research Restoration Center. As professionals, they were riveted by the opportunity to work with such extraordinarily ancient fabrics and lacquer and gave us invaluable and disinterested assistance. We especially appreciated the workshops they organized for our restorers. The hands of Natalia P. Sinitsina and Olesia S. Popova have brought us back from non-existence fragments of a unique woolen embroidered cloth, a truly sensational find. фыVladimir Simonov, who had developed methods for the preservation of things made of lacquer, helped us to save from ruin lacquer cups of the Khan epoch covered with painting and marked with exceptional Xiongnu tamgas and hieroglyphic inscriptions.

Concurrent with the restoration, our scientists are investigating the whole variety of things and materials found in the 20th Noin-Ula mound, using a set of physical and chemical methods. This, however, is a different subject.

What threadbare silks…

Before starting restoration of archaeological fabrics, we should determine, in the first place, whether such a restoration is possible at all because some samples cannot stand any mechanical impact. This occurs when the fabric fibers have been damaged so much that they are only connected by ground or metal oxides. In this case, the sample can be preserved using chemical agents that will make this connection even stronger.

If the fabric fiber is elastic enough to endure some manipulations, we should start with mechanical cleaning of the fabric’s surface coincidentally with its straightening or smoothing, taking proper care of all the seams, layers and details.

Mechanical cleaning can be done with a brush, soft sponges or a vacuum-cleaner with controlled intake power and supplied with special attachments.

After mechanical cleaning has been completed, it should be assessed whether a wet cleaning or washing is possible and, if yes, what is the best way to do it. If water is likely to damage the artifact seriously—even if some supporting substances are used—wet cleaning is done with tampons or the artifact is washed on absorbent paper or a net. If an artifact is in a good condition, it can be submerged in water and a neutral washing detergent (Hostapoon) can even be applied.

After the piece of fabric has been washed and “rinsed” (by changing water until no sediment or lather forms), it should assume its original shape if it is an item of garment or just be smoothed out if it is a fragment of fabric. This operation can be performed on glass or film: moist fabric is put on a smooth surface and carefully straightened along the end and the filling until is takes its original size and shape. After that, the fabric’s surface is covered with rectangular sheets of glass of a required size and ground edges in such a way that there is some room left in between. This is usually enough to prevent the folds and creases that formed when the fabric was buried from shrinking it back to its previous form. If necessary, some weight can be put on top of the glass. After the fabric has dried and glass sheets and weights have been removed, the artifact looks quite smooth (provided that its end and filling threads have been straightened properly).

As experience shows, fabrics processed in this way remain elastic and preserve their brightness and luster longer than fabrics processed with fixing and moisturizing substances or fusing glue. It goes without saying that the conditions in which artifacts are kept are very important.

The aim of fabric restoration is to preserve it in the same or even better state for as long as possible. This allows investigation of the fabric bits using all the methods currently known, their reconstruction, and developing an insight into their ancient applications. Also, the fabric will thus be preserved for future examination.

Mystery of eighteen fragments

We have found eighteen large and medium-size fragments and a multitude of small shreds and ropes of the carpet that had once been a rectangular woolen cloth, red in color, ornamented with parallel rows of circles made out of woolen twisted rope. The cloth was attached to a black and light-brown double-layered felt and had a felt border decorated with applications.

To clean and wash the carpet fragments, we applied the technology of ancient fabric restoration developed at the Europe-largest Abegg-Stiftung Restoration Center, Switzerland. We have successfully used this technology for many years to restore the fabrics and felts dug from the frozen Pazyryk mounds.

First of all, the fragments of the Noin-Ula carpet had to undergo thorough mechanical dry cleaning, which would make possible its subsequent washing. The clay crust covering the fabric surface was broken by wooden sticks or thick and blunt needles; the dirt was removed with the help of a vacuum-cleaner with thin attachments, switched to a low-power mode. In this way both sides of the carpet bits were cleaned. The fabric was then moisturized using a spray so that the creases could be straightened, and the decorative twisted rope was put back to the fabric where it had been, as the traces showed. To avoid any fabric loss or transformation during washing, all the fragments were put inside a kapron net.

The artifacts were washed in a special washing bath, with distilled water and the neutral washing detergent Hostapoоn. The detergent was churned with the help of a sponge in a small volume of warm distilled water. The carpet bits spread about the bath were covered with the lather and left for 30 minutes, after which the bath was filled with water so as to cover the bits completely. The fabric surface was then sponged gently, and dirty spots were washed with a soft brush. The water was let out, the fragments were turned over, covered with lather again, and the whole process was repeated. After that the fabric was rinsed carefully: the bath was filled and emptied many times so that no traces of dirt or washing detergent were left.

After that, the fragments were spread on glass to dry, and excessive moisture was removed with absorbent paper. The fabric was straightened while wet; in the tears the threads were lain in the direction of the end and filling; details of the ornament were put in their original places.

The dried fabric bits were partially or completely bonded to virgin silk gauz, brown-colored and sprayed thinly by the polymer А-45К. This fabric-to-fabric bonding was performed with the help of an electric spatula. When the doubling fabric was heated, the polymer melted, and the gauz fused to the carpet bit. (We would like to express our sincere thanks to Natalia P. Sinitsina, who familiarized us with this restoration technique and kindly shared with us her materials). The decorative ropes were attached using the Laskaux glue. Fragments of the felt border were also bonded; and the felt application restored as much as possible.

The lacquer cup challenges restorers

Preservation of lacquer artifacts was a task we had never dealt with before. Therefore, anticipating finding some things coated with lacquer, we applied for help (before starting the diggings) to the well-known expert in the East-Asian lacquers Vladimir G. Simonov, leading restorer with the Grabar Russian Art and Research Restoration Center. Specialists of the Center have been restoring East-Asian lacquer artifacts since the 1980s. Our problem, however, was that the wooden base of the lacquer artifacts was extremely damp, which was a revolutionary challenge for the national restoration science—in actual fact, we had to create a new technique.

The lacquer artifacts have survived, but the conditions inside the burial were harsh. Under the pressure of the ground, the lacquer cups deformed: they lost handles, became flattened or fell apart into bits. The lacquer has partially peeled off, and wood showed in the cracks. In order to avoid quick drying and consequent peeling of the lacquer, we did preliminary, or field, preservation.

Field preservation of the lacquer cups’ wooden base was removing clay and soaking it, using a brush, with 10—20% water solution of polyethylene glycol (PEG-400). The soaked artifacts were kept and transported in air-proof trays.

The following stage—preservation in laboratory conditions—tackled the task of further stabilization of the cups’ wood structure. The same conserving agent, polyethylene glycol, but with a higher molecular mass (PEG-400), was used. A similar technique has been applied to strengthen the wet archaeological wood extracted from the frozen Pazyryk mounds of the Mountainous Altai.

After that we faced the problem of drying: removing moisture from the artifacts in a way that would change their look as little as possible. To avoid the curling of lacquer, it is necessary to fix it on a base before the drying. However, the wet deformed wooden base and some of its fragments, as well as configuration of the lacquer layers were such that it was impossible to fix the lacquer in the usual way (using a bag of sand as a weight). So we designed and made a special device for fixing the curled lacquer on strongly curved bits and on fragments featuring an intricate relief. The moisture was removed by filling the space around a cup bit with a sorbent; the condition of the bit and moisture content were kept under continual control. We used fish glue with an antiseptic as a strengthening agent because it works well when all other glues have no effect. So that the lacquer did not swell or curl during the drying, a fish glue solution had to be injected underneath, the lacquer was then pressed and fixed using the device mentioned above. In this case the glue dried together with the artifact, keeping the lacquer glued to the base. Since it was impossible to inject glue under every bit of curled lacquer because the artifact was wet, we first fixed it only where it was doable, and moved on step by step. Thanks to this approach, not a single lacquer fragment has been lost or broken.

The following step was fixing the lacquer layer on dried cups and their fragments. Here we applied the methods developed earlier, which have been widely used in working on museum exhibits. Our approach varied depending on the conditions of lacquer application. For instance, thick and hard lacquer was fixed using wax-resin paste. The melted paste was inserted under the lacquer, and the surface was then ironed with a warm spatula. This was the only possible way to reform pronounced warps of lacquer as no solvent applicable in restoration can emolliate East-Asian lacquer; it only softens in response to heat. The paste turned out to be convenient because it filled unevenness and hollows of the destructed wooden base soaked with polyethylene glycol. A border was made around the lacquer layers that went beyond the fragments’ base with a view to protecting it from mechanical action.

A most complicated job was restoration of the artifacts’ shape by gluing the fragments together, very much like they glue together a broken cup. Our bits, however, had no clear borders and, thus, could not be fixed, so we had to glue them together literally on our hands. We needed a glue of high viscosity—after a few tests we found that highly concentrated fish glue was the best as it managed to join the bits of cups together and hold them in a proper position until they dried completely. Sometimes, the fragments had only two or three contact points. It should be noted that though, as a rule, restorers are advised against using different fixing substances on the same object, we had to do it. As there was no other way to preserve an artifact, however, we had to apply protein glue, synthetic glues, and wax-resin paste to fix the lacquer when it dries and to stick the bits together.

Preservation of the unique monuments of the Chinese origin dating back to the Khan epoch has not been completed yet, but we have managed to find an approach to solving this problem.

Gold rusts and steel rots…*

Almost all metals are subject to corrosion, i.e., loss of qualities characteristic of metal and subsequent formation of mineral layers.

When a metal is in the earth, its corrosion depends on the soil’s acidity, porosity, and presence of solvable salts. These salts conduct electric current in a wet soil—in other words, act as an electrolyte. An electrochemical reaction occurs—interaction of two inhomogeneous metals in the presence of a salty solution—and the less noble metal corrodes while the nobler metal stays intact. So Anna Akhmatova was not right—gold does not rust. Metals go in the following top-down order: gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, and iron.

Metal artifacts dug out of the earth are always covered with a layer of oxides, various salts, stuck-on ground, etc., which alters their shape and distorts their surface; and variations in moisture and the presence of the air oxygen contribute to further destruction and may lead to a complete loss of an artifact.

* Anna Akhmatova, Russian poet