Ludomania in Oriental Style

The relatively recent casino boom in Russia and resulting gambling addiction (not as deadly as COVID-19, but not less contagious) has aroused public interest in this issue (the Russian for «gambling» is azartnye igry) and in excitement (azart) per se. We wished to learn or recall what role games for money played in Old Russia and what the situation is in other countries and peoples.

If we look at etymology, we’ll find out that the Russian language borrowed the word azart from French, where it had come, possibly also through an intermediate language, from Arabic, where al-Zahr means a «dice.» That’s a twist because dice games, dating to the Bronze Age, started as fortune-telling, kind of playing with Fate. Hence, probably, the ambiguity of the word azart in Russian. There can be different kinds of excitement, and there’s nothing bad about some of them. Excitement in work, for example, or excitement in achieving a goal, and the goal doesn’t have to be money. We will allow ourselves to quote a verse from the brilliant poem If by Rudyard Kipling:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss.

The narrator can be accused of many sins: adventurism, swagger, pride (a deadly sin!), but not of profit-seeking.

Note that the different kinds of excitement could sometimes get on well inside one person. One of the best examples is the great Russian poet Pushkin. The Boldino autumn, the height of his genius, could hardly have been possible without the frantic excitement in writing; on the other hand, the poet would play cards for days on end, mostly losing. When he died, his gambling debts amounted to 120,000 roubles, the sum he could have hardly paid off.

The East, where gambling became popular in ancient times, was well familiar with different kinds of excitement. In order to harness bad excitement and turn it into a good one, the Chinese and especially Japanese intellectuals tried to make literary activity - poetry writing, above all - an indispensable element of the game.

It would be a great exaggeration to state that the Chinese scribes or, much less, the Japanese Samurai preferred exquisite literary amusement to the stupidly simple dice games. But at least they tried, and to this audacious attempt we have dedicated our paper

Today game is perceived first of all as a synonym of greed and gambling, but originally the game element was an important part of social life. In contemporary cultural studies, a game is a form-building, with respect to culture itself, human activity; moreover, the emergence of games along with the competition feature typical of them have been noted already at the biological level, before any culture (Huizinga, 1992).

If we consider games as a phenomenon derivative from the cultural experience of mankind, then their position can be defined as interfacial between the world of introspection (philosophy, science, religion, etc.) and the world that escapes from introspection (ritual, body practices, feelings). In the contemporary interpretation, a game is a non-productive human activity motivated not by the achievement of any practical result, but by playing it: A game as a field of activity and life opposed to serious, non-game reality has specific symbolic convention making a person free within the game limits.

Owing to symbolic convention of games, there is a possibility to simulate conflict situations whose solution is either difficult, or impossible in the practical sphere of activity. At the dawn of mankind, the aesthetic and ethic ideals were formed through play behavior. Games enabled people to soar above the mundane, to create the Universe of their own, thus becoming similar to deities. This implies a close relationship between games and rituals: not without reason games were an integral part of cults in traditional communities. And though with the development of culture, games were desacralized, the indications of their strong association with providence have been retained in many small details and even in prejudices related to game practice.

The self value originally inherent in games does not presuppose any material profit for the participants. However, with complicating social relationships the game participants’ aspiration for self-affirmation and leadership increased, and with developing market relations a victory in games even began to be estimated as money equivalent. The commercialization of games has contributed to that the urge towards personal success and benefit now in increasing frequency acquires a pathological character.

Since the action of internal mechanisms of gambling which is akin to drug addiction has not yet been fully understood, no effective means to treat the game addiction exists. The search for such a panacea is being performed by both biochemists and psychologists, but one of its most interesting variants in the sphere of culture seems to be the one suggested several centuries ago. It is the Japanese experience in creating intellectual card games.

Seashell Entertainment

The excitement in games has long since been peculiar to oriental people, and the ancient Chinese treatise Zhuan-zi 庄子。达生(第十九), dated by the end of the 4th‑3rd centuries B. C., expressively says about it.: “Who is skilled in a game with tile at stake becomes agitated playing for a [silver] buckle and completely loses his mind playing for gold. The skill is the same, but as soon as something valuable appears, all the attention is now concentrated on the external. And while being concentrated on the external, one loses attention to the internal” (恶往而不暇。以瓦注者巧。以钩注者惮。以黄金注者殙。其巧一也。而有所矜。则重外也。凡外重者内。

The Confucian tradition that became popular in many countries of the Far East in order to curb mean passions prescribed “a noble gentleman” not to waste his powers on idle affairs, but instead to direct them on his own spiritual perfection and devoted service to his sovereign. This model did not leave room for play behavior and competition because, as Confucius taught, “a perfect man has no motives to enter a competition”, with the only exception for archery (子曰君子无所争必也射呼)(论语。八佾).

The Confucian ideology had later greatly influenced the development of Japanese social consciousness, including the formation of the well-known Samurai code Bushido (武士道). In the first place, a true warrior should have competed with himself and not to be diverted from the Path of Service.

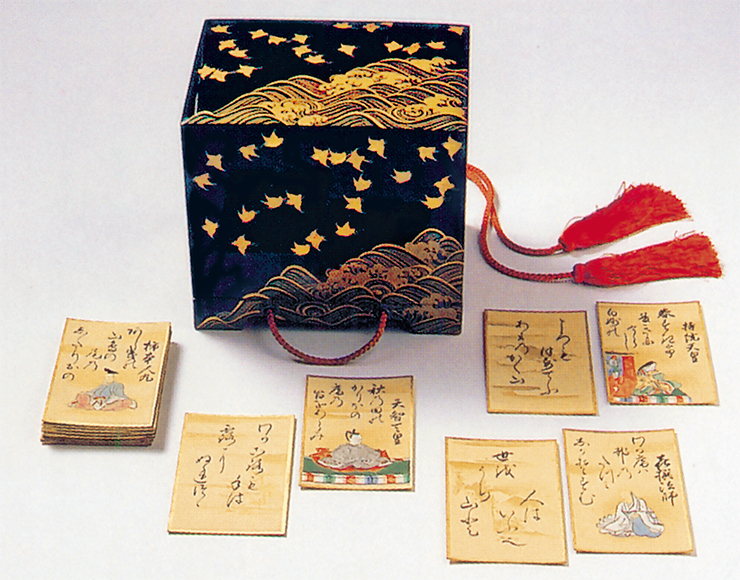

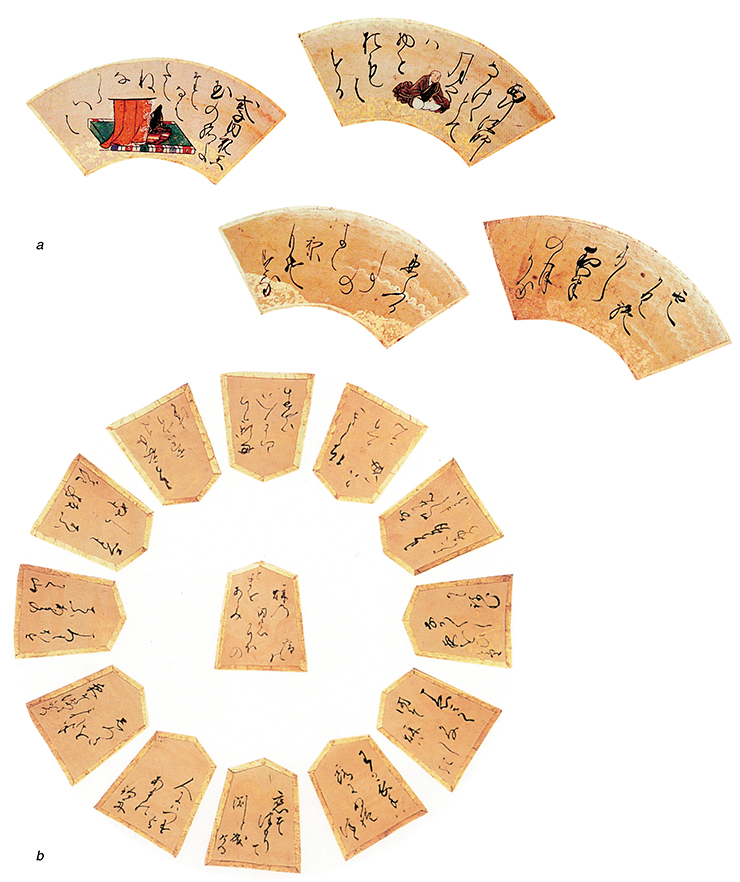

Of course, theoretical premises were far from being always implemented. Characteristic in this aspect is the development of a game called kaiawase or kaiooi (“clam shell matching game”) that used to be popular among the Japanese noble women in the Heian (the 8—12th centuries) period. The game consisted in matching the halves of rare and unusual hamaguri clam shells by their shape, color and size. The player who got the greatest number of matching halves was declared the winner.

Originally kaiawase was played only in aristocratic circles, but already by the Edo period (the beginning of the 17th century) the “seashell pastime” had become widespread also among ordinary people. In order to enlarge the circle of potential players, the game content was essentially changed by drawing on the internal part of shells either pictures or verse lines. The play with these seashells had became later the prototype of card games based on good knowledge of both tanka or pentastich from classical anthologies and poetic images of famous pieces, for example “The Tale of Prince Genji ” (“Genji- monogatari”) created in the10—11th century.

Poetic Cards Uta-Karuta

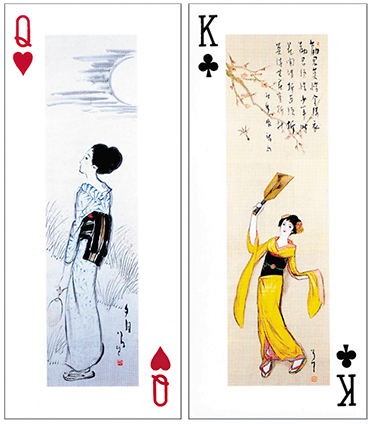

The Europeans who appeared in the Japanese Archipelago in the middle of the 16th century had brought with them paper cards which after all completely substituted for fragile seashells. By the word “card” (karuta, garuta) borrowed from the Portuguese carta a special kind of thick paper was first meant.

The first cards of Japanese production were printed in a settlement Miike (now Omuta city) on Kusu Island. The craftsmen did not simply copy Western samples, but created their own versions where as suits “cups”, “coins”, “batons”, and “swords” were used, and as “images” (high rank cards) “queen”, “rider”, “commander”, “dragon”, etc. During the century several kinds of Europeanized card games had been created which endured both a rapid development and periods of being banned by the authorities.

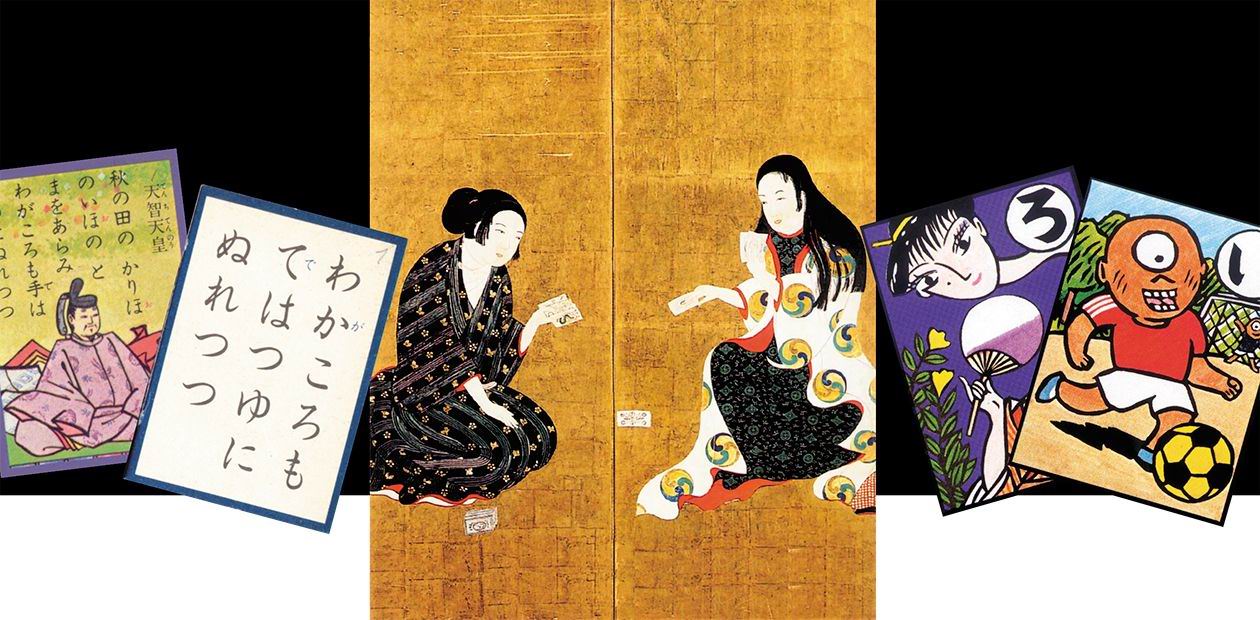

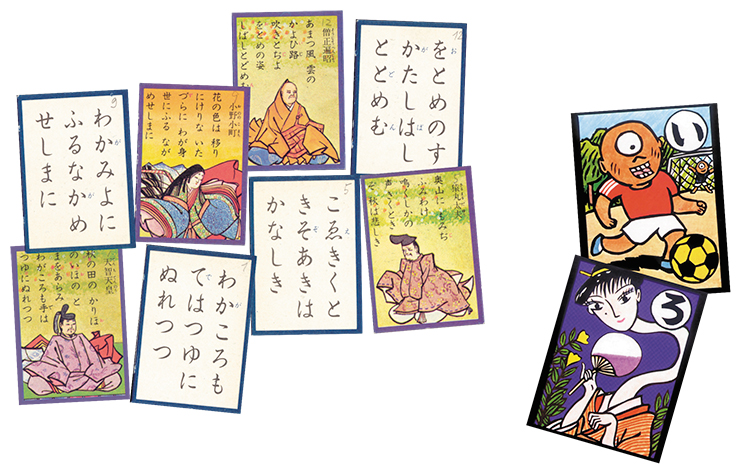

As regards the Japanese line of card games, in the middle of the 17th century there already existed “poetic cards” uta-karuta, more resembling lotto, developed on the basis of the poetical anthology of the 13th century “Hyakunin isshu” (“ Hundred Poems by Hundred Poets”) composed by a distinguished poet and philologist Fujiwara-no Teika. This game equally combines cultural educational elements and the excitement of playing it.. It should be noted that at first the verses from other collections were also used, but already by the middle of the 19th century uta-karuta started to mean only the cards based on “One Hundred Poems”. Therefore they were also called hyakunin-isshu-karuta. Moreover, it is due to this poetic card game the anthology itself had gained special popularity.

In the Meiji period (the middle of the 18th — the beginning of the 19th centuries) the well-known publisher Kuroiva Ruiko had designed the contemporary rules of the game after which the competitions in poetical cards started to be held on the New Year Eve festivals. This tradition has survived until now. Over a hundred thousand fans of poetical cards regularly participate in competitions all over Japan. About five thousand persons have “dans” (classes). There is a special commercial league that annually organizes qualification tournaments in which fifty persons compete for the title of meijin master.

“Drive the Piles Protruding”

Yet another intellectual game, iroha-karuta — “cards with proverbs”, became most popular in Japanese society. These cards represent a kind of anthology of folk proverbs and Buddhist and Confucian aphorisms where one or several maxima correspond to each alphabet character.

The invention of iroha alphabet (called so by the first three characters: i-ro-ha) is traditionally attributed to Kobo Daishi, a legendary Buddhist monk (774—835), better known by his monk name Kukai. There exists a supposition that Kukai, being a skilled calligraphist, created the characters of hiragana syllabary, based on Chinese hieroglyphs, which became part and parcel of the written Japanese language.

It is this new syllabary that was fixed in the poetic iroha alphabet consisting of 48 (initially 47) characters and based on an excerpt from the Buddhist “Nirvana Sutras”. As a result, a balanced poem with deep philosophical meaning was composed. (In Russian it is presented in the brilliant translation of Academician N. Konrad.)

Iro ha niho heto

chiri nuru wo

waka yo tare so

tsune nara mu

ui no oku yama

kefu koete

asaki yume mishi

wehi mo sesu (n)

Even colours and sweet perfume.

Will eventually fade

Even our world

Is not eternal

The deep mountains of vanity

Cross them today

And superficial dreams

Shall no longer delude you.

As regards the iroha cards, they appeared at the end of the Muromachi period (the 16th century). Several local variants of them existed, but all of them were based on the same principle. The iroha deck consists of 96 (48x2) cards, half of them is images with alphabet characters, and the other half is texts of proverbs and aphorisms. The players must find as many correspondences between these two sections as possible, which requires good knowledge of the literary language with all its richness.

The texts on the iroha cards are, as a rule, moral or didactic utterances, often filled with good-natured humor. Let us show some typical examples: “Send your dear child on a voyage”; “The home where people are laughing draws luck”; “Excessive politeness changes into rudeness”; “Sometimes even a monkey falls from the tree”; “A bee to a crying face”.

Here we can also mention the well-known utterance “to drive the piles protruding” which is interpreted by many culture scientists as one of the basic principles of the Japanese society functioning up to the present time. The meaning of this statement is that first of all it is essential to fulfill the common task without making oneself distinguished to the detriment of the dominant order, which, by the way, completely excludes competition.

Cards as ABC-books and Encyclopedias

Since Japanese phraseology is indeed vast, there are many sets of cards with different collections of proverbs and aphorisms. It is possible to distinguish three groups of maxima corresponding to different card sets: kamigata-karuta proverbs popular in the Kamigata region (the territory referring to Kyoto and Osaka); chukyo-karuta proverbs popular in the Chukyo region (between Tokyo and Kyoto, with the center near Nagoya); edo-karuta proverbs popular in the historical centers of Japan and most of all in Edo (the name of Tokyo until 1868). It should be noted that the chukyo-karuta utterances being rather peculiar at present are almost incomprehensible to most people of Japan, and therefore they are gradually falling out of use.

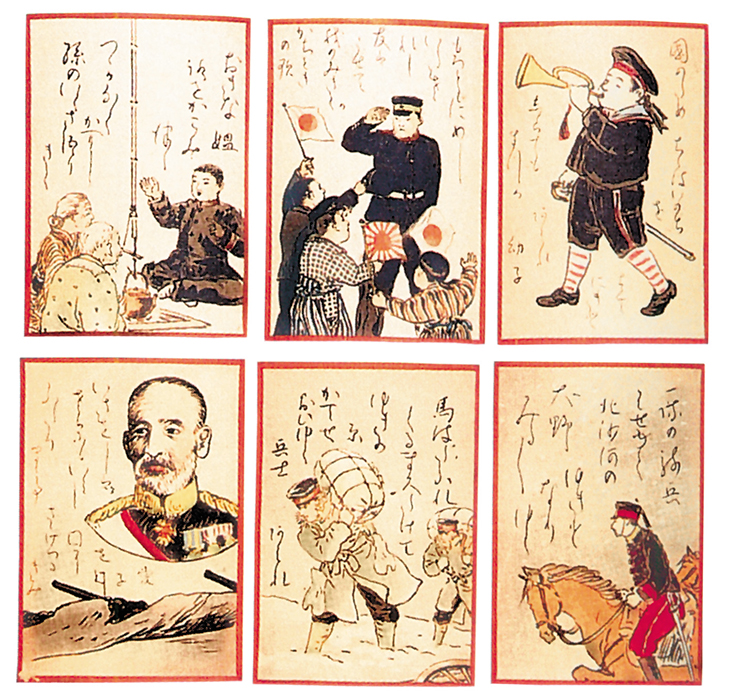

On the basis of the poetical alphabet, card sets with various topics have been constantly created. Among most original we can mention yokai-karuta cards, then obake-karuta (Monster Cards) which appeared in the period between Edo and Meiji. Instead of classical proverbs and aphorisms these cards operated the maxima and different stories relating to ghosts and werewolves from the traditional Japanese demonology — popular images of the traditional Kabuki Theater.

Apart from the function of play, iroha cards performed yet another one. They served as an illustrated ABC-book and helped the beginners to master the alphabet, and they also enriched the players with the information about the expressive means of the language. When collected together, the quotations and aphorisms served as a kind of verbal weapons allowing the educated people to rebuff possible attacks of the opponents in the course of discussion.

The iroha poems were also used as calligraphic samples, so their other name is tenarai-uta which can be translated as “poems for calligraphy”. This is the result of the cultural influence of the great continental neighbor of Japan, i. e. China, where, along with classical Confucian books comprising the basis of the spiritual upbringing in the traditional culture, rhymed hieroglyphic handwriting models had long since existed, and the knowledge about the world was given there in the form of a play.

Twelve Months, Flowers, and Trees

Though many of the intellectual Japanese card games have appeared not so long ago, all of them are in their content based on the centuries-old cultural tradition. This concerns also the so called hanafuda (or hana-karuta) “flower cards” invented in 1818—1843. One of the motives for their creation was a desire to circumvent the official ban on the card games of the European type that existed in that time. These cards which give a full representation of the sensual perception of all four seasons of the year in the artistic poetical tradition were the result of the collective creative work of the Japanese people. And today, despite that the Chinese game mah-jong (Majiang) and ordinary European cards, in other words, all kinds of gambling games that have come from abroad, are widespread in Japan the hanafuda cards remain popular as a purely national play being a specific phenomenon of Japanese culture.

Flowers and birds of four seasons, tanjaku inscriptions with poems (an oblong sheet of paper with poems in the genre of tanka), exquisite images — all this could appear only in the Country of the Rising Sun. In the form the “flower cards” have come to us, they are a deck of 48 sheets with pictures of trees, flowers, and plants corresponding to the four seasons of the year: pine, plum, sakura, wisteria, iris, peony, lespedeza, silver grass (Miskanthus), chrysanthemum, maple, willow, and paulownia that are inscribed in various stories.

It is accepted that flowers on hanafuda cards correspond to 12 months of the solar calendar (despite the fact that the solar Gregorian calendar was not introduced in Japan until 1873, the beginning of the Meiji period), whereas the plants and poetic images associated with them correspond to months of the lunar calendar traditional for the East. Therefore because of the difference between lunar and solar calendars, there are some discrepancies among the “flower cards”. For example, the plants such as June peony and December paulownia should actually be related to April plants, while November willow to May plants. For this reason many of the plants, birds, and flowers collected in “flower cards” do not correspond to the real season and, hence, are not reliable calendar-time evidence. All this emphasizes the convention of the game space separating it from the everyday reality.

The symbols of flowers and trees used in hanafuda cards are chosen not randomly. For many centuries all of them played a noticeable role in the traditional culture of Japan retaining their importance also in the contemporary life. It is enough to mention the truly all national tradition of feasting the eyes with sakura blooming. Note that in many cases the meaning of a particular plant in the cultural life of the Japanese people is predetermined by that gigantic complex of spiritual traditions which Japan has inherited from China. Having creatively transformed and developed the borrowed elements, the collective genius of the Japanese people has managed to originate a specific manner to artistically assimilate the reality.

Over 30 types of playing “flower cards” are known in Japan and also in Korea (this game called hwathu in Korean came from Japan and even acquired its own ethnic features). Despite the fact that by a number of criteria these games are similar to the European gambling card game (we mean a complicated and ramified system of rules, which requires maximum attention and concentration from players; the presence of numerous additional combinations, bonuses, and bids), they retain the originality of their internal content. To play the hana-karuta game implies the excellent knowledge of the cultural historical context and of a great number of customs concerning the material and spiritual life of the people of Southeast Asia which had been formed for several centuries.

To Learn by Play

At present in Japan a great many of the so called kyoiku-karuta “educational cards” on the most diverse fields of knowledge are published. They include literature, native language, folklore, art, geography, history, astronomy, chemistry, etc. As for the presentation of the material, all of them are based on visual aids widely used by Japanese pedagogues in their teaching practice. Some sets (for example, with reproductions of engravings of famous painters or photos of famous feudal castles) are also used to make Japanese culture popular among the foreigners.

At present in Japan a great many of the so called kyoiku-karuta “educational cards” on the most diverse fields of knowledge are published. They include literature, native language, folklore, art, geography, history, astronomy, chemistry, etc. As for the presentation of the material, all of them are based on visual aids widely used by Japanese pedagogues in their teaching practice. Some sets (for example, with reproductions of engravings of famous painters or photos of famous feudal castles) are also used to make Japanese culture popular among the foreigners.

Therefore, the card games filled with “high” content (poetry, literary allusions, religious and cultural symbols) allowed the members of the intellectual elite not only to satisfy the delight of gambling, somehow inherent in people, without losing face, but also to obtain and memorize new knowledge. It was quite Confucian-like: “… to learn and all the time to practise what they have learned — is it not one of the pleasures?” (子曰学而时习之不亦说呼).

Very gently but steadily, like in aikido, the passion for playing cards was directed onto the goals of upbringing and education in order to thereby preclude, at least partly, the possibility of a pathological development of this predilection. Of course, the value of this experiment should not be exaggerated because no panacea from all diseases, including social ones, exists. Japan, in particular, has not avoided the epidemic of computer games, which is maybe facilitated by their hidden relationship with high technologies. However, even in this sphere the potential of intellectual card games is far from being exhausted. Most of them now exist in computer variants, and on-line competitions are regularly held. In the Internet permanent sites informing about card championships, the activity of fan clubs, new types of cards are actively functioning; both the conceptual and sporting aspects of intellectual games are actively discussed in forums.

As regards the names of different types of cards, when the emphasis is made on the continuity of historical literary traditions, the word karuta is used in the name which is understood in the contemporary language as already native Japanese; but if the design of cards underlines the idea borrowed from the West, the words toranpu (from the English trump) or kado (from the English card) are used.

There is also another interesting sphere of the application of playing cards in Japanese spiritual culture. It is traditional elite arts of the tea ceremony sado and the incense ceremony kodo. There exist special cards for them made of thin wood plates and decorated with diverse flower ornaments comprising, like in the case of hanafuda cards, a special plant code of Japanese culture. These cards are used to evaluate the skill, as well as to establish the order of priority for the ceremony participants to take part in the actions whose purpose (like in all the Eastern entertainments) is not only pleasant pastime but training the spiritual and physical abilities of the participants.

In conclusion of our survey on the intellectual card games of Japan, we would like to raise a question about the role of play behavior whose elements in some way or another reveal themselves in different fields of spiritual culture of China, Japan, and Korea. These types of creativity, which did not symbolize the conflicts of their time, had compensated for the lack of real freedom in highly regulated communities of the East.

References

Huizinga J. Homo Ludens (A Study of the Play-element in Culture), Moscow, Progress-Akademiya, 1992. [in Russian[.

Hyakunin Isshu No Sekai (The World of Hyakunin Isshu). Kioto: 2006. [in Japanese].

Karuta-no Sekai (The World of Playing Cards) / Composed by Ebashi Takashi and Yokoyama Keiichi. Omuta: Miike Playing-Card Memorial Museum, 2003. [in Japanese].

Morita Seigo. Iroha Karuta Banashi (Everything about ancient “iroha” cards). Tokyo: Kyuryudo, 1970 [in Japanese].

The authors and the editorial board are grateful to the officials and workers of the Miike Playing-Card Memorial Museum (Omuta, Fukuoka prefecture), Art Museum of Shoukado (Kyoto) and City historical museum (Sendai), as well as to Professor of the University of Hosei Mr. Ebasi Takashi (Tokyo, Japan) for the illustrative materials