Our Neighbors: The Forest Nenets. Traditional Medicine

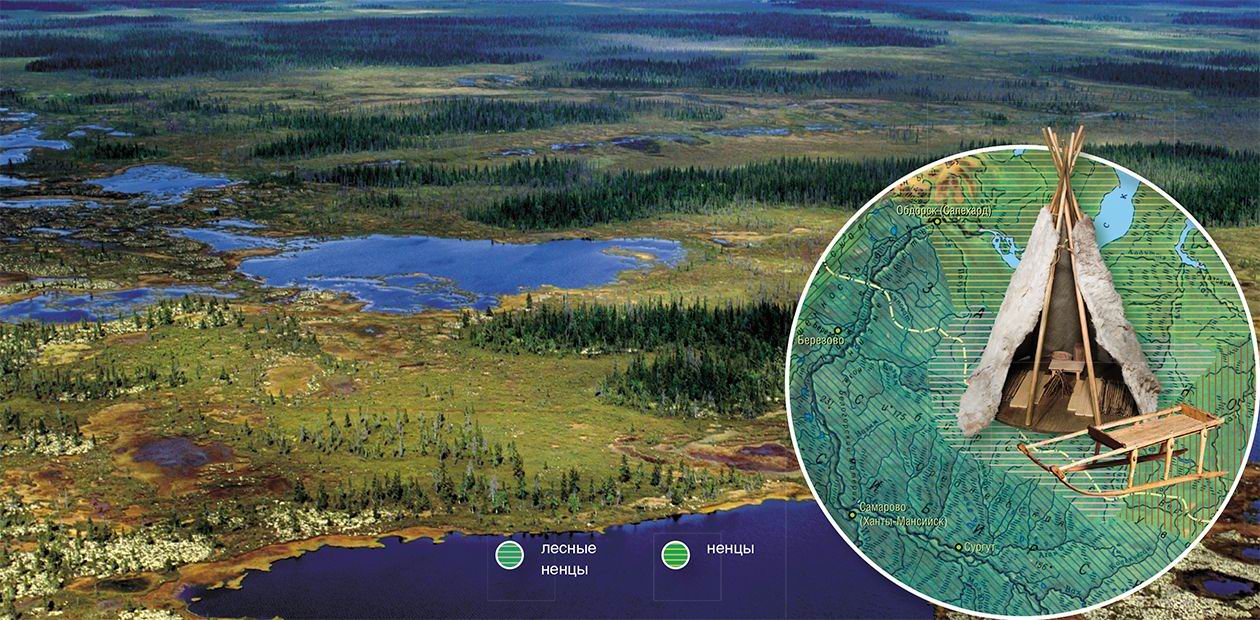

We offer our readers some chapters from the book The Forest Nenets, which is the result of the long-term project “Our Neighbors: The Forest Nenets”. The aim of the project is to study and preserve the material and spiritual culture of the Forest Nenets, a small ethnic group living in the southern part of the Yamal-Nenetsk Autonomous District (“YNAD”) in the Pur River basin. The project is quite unique because it was carried out by the workers of the Gubkinskiy Museum of North Development jointly with the natives, who still live according to their traditions. The natives recorded and described their daily routine life. For this purpose, the Museum donated to them tape recorders, video and photo equipment. In this way, the daily routine of Nentsy camps was “self-documented” over several years.*

*M. I. Gardamshina, N. A. Chebotaeva, E. V. Kalitenko, G. P. Savrasova The Forest Nenets. Novosibirsk: INFOLIO, 2006, 288 pages with illustrations ISBN 5-89590-086-0

Folk medicine is a part of traditional culture and exists as an area of specific knowledge connected with rational and irrational concepts. Folk medicine of the Forest Nenets was greatly influenced by their religious and cosmogonical concepts based on one of early forms of religion, animism, i.e. personification of live and dead nature.

Shaman and medicine man Gennadiy Petrovich Kolokolets from Kharampur trading station cured people by “sucking out” the disease from the body. The Forest Nenets Adi Dyokhalevich Pyak says, “Kolokolets was doing it in a dark chum (without fire). After having drunk a tincture of toadstools and taken his drum and mallet in his hands, he began to sing quietly. Suddenly he stopped singing and, taking me from behind, put me on his toes. I felt a knife blade touching my breast. When I realized that the knife was off, the shaman fell on the bed. In fear, I cried at the top of my lungs: “Help!” The men opened the chum’s curtain. We saw the shaman tossing about in convulsions. The assistants raised him, hopping and making rounds by the sun, and crying out “Hov, hov, hov!” Then the shaman took my head into his hands and sucked my disease out of my head with his mouth. I felt so light in my chest.”The head deity of the Forest Nenets is Num, god of heaven, who created the forest, animals and people. He watches his creations but does not interfere with earthly matters. For that he has assistants — spirits, who are masters of the earth, rivers, lakes, wind, and fire. In recent past each person’s health was considered to be connected with the attitude of those spirits to people. In the eyes of the Forest Nenets, the spirits personified two opposite forces — good and evil. Diseases, wounds and injuries were, in their view, the outcome of evil forces, the result of nature’s spirits interfering in their life or of the magical impact of another person’s evil will. The breaking of taboos, customs and rituals was always considered one of the main reasons that allowed the evil spirits to penetrate into a human body and meddle with his or her life. The Nenets strongly believed that not only the spirits of the Lower world could punish people with diseases, but also personal protectors, family spirits, or any supernatural creatures inhabiting the Middle and Upper worlds.

The treatment of the diseases which were caused by something visible (an injury, chilblain, burn) was usually rational. However, when having internal or mental diseases, whose cause was incomprehensible to the Forest Nenets, they turned for help to shamans, who performed the role of healers scaring off the illness-bringing spirits along with carrying out other functions.

Usually kamlanie* (the shaman’s performance) took place in the evening, in half-darkness, next to the fireplace, by the sounds of the drum, and continued for several hours. As a rule, kamlanie was accompanied by the shaman’s falling into a trance. To achieve this state, shamans often used toadstools, which they dried in the sun, cut very small, mixed with water and then swallowed. To enhance the effect of toadstools, shamans chewed the dried pieces together with tobacco, washing everything down with a small amount of water. To help the diseased, shamans employed different means; the main condition was exerting their influence on the patient’s psyche and establishing the patient’s full trust for the healer. For that they used ritual masks (made of wood, bark, cloth, metal) and luminous effects. Rhythmic drumming, incantations, singing, and the fuddling smell of burning ledum were supposed to help to stave off from the patient the deliberate plots of the evil spirits.

To perform the ceremony of purification from filth and of fumigation of the chum, pieces of skin taken from the front paw of an otter are usedAs a rule, while treating people shamans used their knowledge of human physiology and anatomy, remedies of various nature and such means of healing as searing, massage, psychotherapy. The main therapeutic factor was various forms of hypnotic suggestion that shamans used in order to mobilize the patient’s body’s defensive mechanisms strengthening his or her faith in recovery.

Slight ailments did not require a shaman’s attention; the evil spirit (disease) could be driven out of the patient’s body by other means, for example, by making sacrifices in sanctuaries. When falling ill, the Nenets also asked for dyan’ kata’s help. Dyan Kata (“Earth’s grandmother”) are dolls-idols, which the Nenets women still have now: they are supposed to be the protectors of women, child-bearing and motherhood; they are worshipped and thoroughly guarded. The Forest Nenets used to believe that without dyan’ kata childbirth can end in tragedy. During labor the woman held the doll on her belly, clutching it with both hands when having contractions, and asking for relief. When contractions grew intense, the woman went down on all fours, and the one who was delivering the baby took the doll and placed it over the mother’s back. Such dolls were put at the head of the bed of an infirm. If dyan’ kata seemed heavy, it meant death for the patient; if it seemed light, the forecast was more favorable.

The forest Nenets got rid of warts with the help of… the Moon. A. V. Golovnev writes that in the very end of July, when there was but a last “scratch” left of the Moon, they would smear the warts with a duck’s blood, go out of doors, stretch their arms toward the Moon and say, ”Moon Old Man, take these pieces of meat…”. P. S. Aliullina recalls how when she was a young child, her grandmother taught her to get rid of the wart on her hand: she had to stretch the arm toward the waning moon from under the chum’s curtain and ask, “Moon, who of the two of you will disappear first?” It was forbidden to tell anybody about it. The girl followed the instructions, and the wart disappeared in a monthA special role in curing illnesses was given to dogs. The Forest Nenets treat the dog in two ways: on the one hand, it guards humans from evil spirits and serves as a good shepherd for reindeer; on the other hand, it is itself an offspring of the Lower world god — Nga. According to legends, dogs have their own spirit-master, who lives in the forest and against whom shamans are helpless. This spirit can inflict a disease on people that makes them lose strength, lose weight and die.

In order to recover, the Forest Nenets who did not have reindeer sacrificed their dog, sending it to the Lower world as compensation. The sacrificial reindeer’s or dog’s nose was put against the sore spot. To get rid of scurvy, the sleigh’s skid or the chum’s doors were smeared with the sacrificial dog’s blood. If the spirit of scurvy came in one’s sleep, the person had to cry out, “Scurvy, you are killing me!”, then immediately to make a cut in a dog’s or a reindeer’s ear and put the blood over the face to prevent the disease in the future.

The Forest Nenets have many legends connected with flora. They believe that spirits often choose as their residence definite (holy) trees. They help people, especially in curing diseases. The branches of such trees were decorated with pieces of bright fabric and skulls of sacrificial animals as a token of gratitude; the trunks were bound with shawls, fabric, skins, etc. The Nenets believed that the one who dared to cut the holy tree was inviting the spirits’ anger, which suggested all kinds of disaster and even death.

The source of rational means of curing diseases for the Forest Nenets was wild nature: plants, animals, and minerals.Many prescriptions have been tested by time, and methods of curing and preventing diseases are widely used today. Children are being treated with the same traditional remedies as adults, but the doses are smaller.

Green pharmacy

Traditional healing practices made (and still do) great use of wild plants in the form of decoctions, infusions and powders. They are not only taken orally but are also used externally — as massages, lotions, rinses, baths, and powderings. The stewed plants are used for compresses. By mixing plants with fat, ointments for external use are created. The most respected tree for the Nenets is the birch. Household utensils are made of birch; birch firewood keeps houses warm. The healing power of birch sap and of the extract of its buds has been known for a long time. The Nenets drink it as tonic when having a cold. The Forest Nenets use chaga (a fungus of the polypori family that grows on birch trunks) for treating many diseases. In the old days, when there was no tea, the Nenets used chaga to make decoction and believed it to possess many healing properties. Chaga was considered to be an effective means of curing toothache, for which they dried it on fire, mixed it with tobacco and water and then put it behind the lip and kept it in the mouth until the ache subsided. Chaga was also used to suppress hunger during long trips.

Some clans of the Forest Nenets consider conifers to be holy, as a symbol of immortality and longevity. According to their legends, the trees possess some magic features. The trees include the larch, from which they used to carve cult sculptures. Its needles were used for preparing anti-scurvy tincture; its cones, for treating pneumonia; and its needles and bark together, for healing festering wounds and abscesses. To treat wounds they also used its tar, for which they first warmed it up over the fire and then put it, warm and soft, against the wound; the tar was held there until it fell off from the healed wound. Sometimes they added bear fat to larch tar. Festering wounds were treated with ointment containing fir tar, for which they mixed the latter with perch or pike fat in equal shares and then boiled the mixture.

Usually the Forest Nenets prepare herbal infusions in summer. They do not practice picking and drying herbs for the future use. The only exception is storing up cedar seeds, a valuable food containing a lot of useful substances. The technique of preparing remedies is not complicated: there is no exact dosing of raw material, complex combinations of herbs are not practiced, no special ware for preparing and storing the remedies is neededTo anesthetize wounds and stop bleeding, the Forest Nenets also used another remedy. They pounded tobacco in a mortar, mixed it with an equal part of ash of the burned tobacco and then added such an amount of water that the powder could stay friable. The mixture was then applied to the wound and pressed hard with the help of birch shavings.

A popular folk remedy for many diseases is ledum, or marsh tea, an evergreen bush with a strong intoxicating smell. In the old days, during epidemics, the Forest Nenets fumigated their settlements and houses with its smoke. Fresh and dry branches are still used in chums to scare off mosquitoes, midges and other insects. Newborns are bathed in its decoction. Another popular medicine is hellebore, an extremely poisonous plant. The Forest Nenets make decoction from its root and use it to purge the bowels from worms. They apply its leaves to wounds as an antiseptic and haemostatic means. To cure scab, a mixture of ledum leaves, hellebore roots and reindeer fat is used.

To prevent scurvy the Forest Nenets ate scurvy-grass, in spite of its bitter taste. In folk medicine, its juice is still considered to be a good means of “blood cleaning”. They also use the usual food of reindeer — reindeer moss — which is applied to sore joints as a compress or to the back and chest when there is a cold. For compresses, the elderly Forest Nenets also pick up toadstools and stand them with vodka.

After encountering the Russians, the Forest Nenets adopted some of their methods of herbal treatment, including those using wild berries. Bilberries and bird cherries were used for curing the upset stomach; blueberry leaves decoction, as an expectorant; cowberry and cloudberry leaves, as a diuretic. Cloudberries, a widely distributed plant of the tundra, were eaten as a tonic, diuretic and sudorific, as well as a headache remedy.

The native Northerners have always appreciated crowberries — an evergreen creeper with black sweetish fruit; they sometimes preferred it to other berries, probably, for its total lack of acid. The Forest Nenets use crowberries to heal stomach-ache, as a diuretic and blood cleansing means; the infusion made from its shoots heals pains in joints.

“Ant baths”

The Forest Nenets began to use animal remedies as their weaponry and hunting techniques became more efficient. For example, the fresh meat or the blood of recently killed animals, which are eaten raw, turned out to be an effective anti-scurvy remedy because of a high content of ascorbic acid and of other vitamins. The internal organs, fat and bile of animals also found their use as medicines.

Goose or bear fat, and cod liver oil are used to heal burns or frostbite. The fat is melted and kept in a cool place. Wild goose fat or black duck fat is considered to be of special value because it is used to heal wounds and different skin diseases such as scab or herpes. Fish oil is used to prevent frostbite: it is applied to the face when people take long rides on reindeer or in snowmobiles. To treat burns or frostbite, people use ointments, i. e. mixtures of fat with the tar of conifers. In the old times the Nenets used thin fibers of birch bark as bandaging material.

“When somebody in the family is sick, they always send for grandmother. She would heal a sore with bear bile and a burn with bear fat. She would rinse a wound with reindeer moss infusion. If the wound festers, she has a ledum solution in store. If a furuncle appears, grandmother applies a flat cake made of inner reindeer fat with larch tar. And the furuncle disappears. When father kills a wood grouse, grandmother dries its stomach and pounds it. It is a remedy for stomachache.” (M. S. and O. B. Prikhodko, Khomani)Bear fat is considered to be the best medicine for colds, and bear bile is a universal treatment for many other ailments. A good medicine for bleeding and purulent wounds is the powder scraped off the cooked bear bones or made of dried pike jaws. To treat earache, they put in the ear tampons made of manufactured threads soaked in polar fox fat or bear fat.

Tinctures of fresh bear bile or reindeer bile are used in massaging rheumatic joints and sore muscles. The Forest Nenets drink small doses of such tinctures when coughing, having short wind or stomach-ache, colic, heart attacks, and jaundice. To prevent various diseases, it is recommended to use one drop of pike bile a day. When eyelids have been inflamed for a long time, their edges are smeared with bear bile or bird bile, a duck feather used as a brush.

The Forest Nenets make wide use of remedies provided by reindeer; first of all, they use new growing antlers filled with blood and covered with short thick hair resembling velvet. The antlers are burned over the fire, then the rest of the hair is scraped off with a sharp knife, and the soft cartilaginous top is eaten. The Nenets suffering from exhaustion or anemia drink kissel (kind of starchy jelly) made of antlers. Decoction is used for treating bedsores and other continuous infectious skin sores. Antlers are believed to be especially good for children and old people as a means of bone strengthening and of postponing aging.

Other parts of the reindeer carcass were also important medicines for the Forest Nenets. When having a cold, a heavy cough or diseases of liver, they drank melted marrow from reindeer legs. The reindeer brain was used for treating vertigo. To treat stomach ulcer, they used the reindeer stomach filled with reindeer moss; the reindeer was supposed to be killed after being put out to morning pasture on moss. The stomach was put on an iron sheet under the red-hot furnace. As its surface was fried, the baked part was taken in as a medicine.

To treat earache, they used melted reindeer marrow along with breast milk and warm fish oil. Before the modern bandaging materials appeared, the Forest Nenets covered huge wounds accompanied with voluminous bleeding with fresh reindeer lungs. The method resembles using a haemostatic sponge in modern medicine.

Hunting led to studying wild animals and their behavior, including their abilities in instinctive self-treatment. For example, a wounded bear tries to cover the wound with snow or to lean against a piece of ice. To get rid of intestinal parasites birds and animals eat toadstools and hellebore. They also take “ant baths” as treatment. The remedies made from ants found their wide use in the folk medicine of the Forest Nenets. When someone had a pain in the joint, they immersed the sore limb into an ant hill for 10-15 minutes. Ants in alcohol were used for preparing an ointment to massage joints and to treat the edges of purulent wounds. For a similar purpose the Forest Nenets collect “ant oil” — viscous yellowish liquid appearing on ant hills in early spring. It is rather rare and is quite valuable.

Metal, stone, fire...

The Forest Nenets heal people with the help of searing, acupuncture and pressing points on the body. At first they performed acupuncture with bone needles, later they began using ordinary sewing needles.

They say that acupuncture used to be performed if a baby was born with asphyxia. They made quick shallow pricks in the fingertips until blood appeared. If there was no effect, the pricks were made in the toetips or in the center of the sole. Sometimes they used the points on the nose, lips, the tip of the tongue.

Summer is believed to be the best time for treating serious diseases and minor ailmentsTo treat arthritis, along with searing, they did acupuncture using several needles simultaneously; to do this they tied the needles in a bundle or drove them into a piece of wood so that their sharp ends would stick out 3–5 mm. The skin over the sore spot was rubbed with chaga ash and then it was hit with this needle impress. Beads of blood appeared on the surface, and the ash penetrated into the skin. The patients who were treated like this have indelible tattoo spots.

One of the most archaic methods is searing. Searing means that definite points on the skin are irritated with a piece of smouldering chaga, a burn follows and a blister appears. The Forest Nenets say that such points used to be known by virtually everybody, especially the elderly. The process of searing goes like this: at first the painful point on the body is found with the help of a splinter or a match, then on it they put a piece of paper with a small hole cut out over the point in order not to burn the skin around. A small amount of chaga, the size of a pin-head is kindled on the knife tip, and then applied to the chosen point. Dry chaga ignites easily, smoulders evenly and emits heat generously.

Searing usually takes from two to three minutes. To support the smouldering of chaga, they wave the knife over it, preventing it from going out. They believe that if the point is chosen right, the burning chaga must jump off from the blister with a slight crackling. Then the paper is removed. The process is repeated until chaga stops jumping off. Then the ash is pressed with the knife tip and left on the skin. The skin is not cleaned before searing, and afterwards no bandage is applied. The Forest Nenets Svetlana Pyak says that when she was a little girl, her arm hurt badly. They performed searing on her wrist in two spots, with the help of chaga. Her arm stopped hurting, but the traces of burns are still visible.

In the case of a headache, searing was made in the neck; in the case of a diseased kidney, in the small of the back. To suppress a heavy cough, they seared points on the back of the hand between the basic phalanges of the ring finger and the little finger, and also points over clavicles. However, searing was never used to treat haemoptysis, heartache, and pregnant women.

To provide first aid to someone who has fainted, the Nenets use another old method — pressing the fingertips or toetips of the victim.

To treat a cold or diseased joints, the Forest Nenets applied compresses of heated sand in a bag. When having gastrointestinal disturbances, they drank gunpowder mixed with water. To stop bleeding, they used elf-bolts (petrified shells), which they scraped with a knife or a file and poured into the wound. The same powder was used as antiseptic if one had a sore throat.

The Forest Nenets treated broken bones with copper. They believed that it made the bones knit faster. A piece of copper was scraped with emery, the powder was mixed with water and then taken orally. According to a popular belief, when one had sore hand joints, one had to put a copper ring on a finger. Its color helped to determine whether the disease was cured. If the inner surface of the ring grew lighter in color, the patient was supposed to get well soon.

Folk hygiene

One of the most important parts of traditional medicine is folk hygiene and methods of preventing diseases.

Thus, the Forest Nenets put on their traditional fur clothes with fur inside right over the naked body. Due to a special cut warmth concentrates inside, and the back, chest and shoulders are kept warm. The slits for arms and head help to regulate the thermal conditions inside clothes.

“Due to the coarseness and tubular shape of hairs, fur replaced baths for our ancestors and for us, too, and relieved the people from building bath-houses in the severe climate. However, no one of our ancestors told us or our grandfathers about these qualities and advantages of reindeer fur. No scientific explanation was offered. That is why we had no idea that the short hairs on reindeer skin cleaned our bodies from dirt, as in a bath-house. Only with time I understood the mechanism of cleaning the body with the help of reindeer clothes: each hair absorbs sweat and breaks off under its weight. That is why our ancestors developed a habit of wearing clothes made only of this material. Besides, reindeer fur can have a psychotherapeutic influence on the nervous system...” [Susoi, 1994, p. 124]Reindeer fur — the traditional material for the Forest Nenets’ clothes — possesses some special hygienic features: when touching human skin, it absorbs moisture; when people move, the fur constantly rubs the skin and promotes blood circulation. The hairs of the fur are hollow, so the fur safely keeps warmth: even newborns are bundled in reindeer skins.

Babies in the tundra never have intertrigos. The Forest Nenets Svetlana Pyak says that when her sister, who had ten children, came to visit her from the tundra, she was surprised to see the intertrigo of Svetlana’s baby, who was wearing a manufactured diaper. She had never seen anything of the kind before. For the cradle, the Forest Nenets use dust of a half-rotten birch trunk, which absorbs moisture very well. The dust of rotten wood is not only hygroscopic but it also emits heat, which is why the baby in the cradle never gets cold even in a hard frost. This method of keeping the baby in the cradle shows its irreplaceability in the severe climate of the North.

The dust of a rotten birch trunk is also used as a hygienic powder. It is poured into mittens and kisas** because it absorbs sweat very well. Besides, the Nenets prepare powder or decoction from chaga, with hygienic purposes. As towels and for hygienic procedures, women used birch shavings, which they stocked in the end of February.

*Kamlanie is the ceremony performed by a shaman

**Kisas are winter fur shoes of native inhabitants of the North