The Kurilskiy nature reserve: at the crossroads of three elements

Many have heard of the Kunashir Island and the Lesser Kuril Ridge as the subject of the ongoing territorial dispute between Russia and Japan. Much fewer people are aware that since 1984, these territories have hosted the State nature reserve “Kurilskiy”, which, together with the Federal State nature preserve “Lesser Kurils”, founded in 1983, is a true gem in the registry of special protection natural territories of Russia. These small patches of land have unique volcanic landscapes, hot springs that equal the world’s best spas, dark conifer rainforests and lush “southern” vegetation, noisy seabird rookeries and coastal waters rich in marine mammals…

The nature of this secluded region owes its unique richness and extreme biodiversity to its position at the intersection of three elements: land, water, and fire.

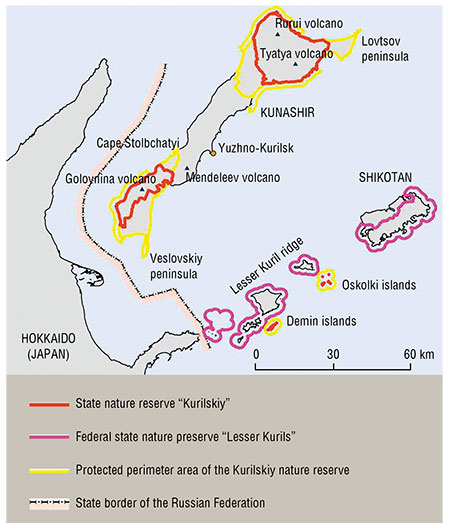

The Kurilskiy nature reserve, occupying a mere 1 % of the territory of the Sakhalin region, is situated on three islands surrounded by a marine protected perimeter area, which occupies over 26 thousand hectares (100 square miles). The Lesser Kurils nature preserve, which is a subject of the reserve, also has a one-mile-wide protected perimeter covering over 40 thousand hectares (over 150 square miles). There is logic in it: the Southern Kurils are among the most biologically productive zones of the ocean, and it is very important to protect and preserve these territories.

The Kurilskiy nature reserve, occupying a mere 1 % of the territory of the Sakhalin region, is situated on three islands surrounded by a marine protected perimeter area, which occupies over 26 thousand hectares (100 square miles). The Lesser Kurils nature preserve, which is a subject of the reserve, also has a one-mile-wide protected perimeter covering over 40 thousand hectares (over 150 square miles). There is logic in it: the Southern Kurils are among the most biologically productive zones of the ocean, and it is very important to protect and preserve these territories.

Moreover, the Kurilskiy nature reserve is one of the two nature reserves in Russia to have active volcanoes. Volcanic activity, including thermal water discharge, actively influences the local natural communities. The Neskuchenskiye hot springs are a good example – it is a fumarolic-thermal zone at the root of the Rurui volcano stretching along 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) of the shoreline that includes about 50 outlets of hot sulfide and hydrosulfuric gases and hot springs, with the water temperature reaching 96 °C (204.8 °F). The local microclimate has made the area a refuge for rare thermophilic reptiles, including one of the largest population of the «rainbow lizard» – the Far Eastern skink (Plestiodon latiscutatus). On the barren acidic soils of the volcanic fumarolic fields grows a fungus known as the Dead Man’s Foot (Pisolithus arrhizus), with fruitbodies that resemble rocks; on the slopes of the Tyatya volcano, one can encounter an endemic plant of the Southern Kurils – the volcano dandelion (Taraxacum vulcanorum).

The surrounding seas leave their mark on the mild oceanic climate of the Kurils, with mild winters and cool summers, especially on the Southern Kurils, where the protected territories are situated. The Kunashir, which is the southernmost island of the Greater Kuril Ridge with the warmest climate, is home to some typical representatives of subtropical flora: for instance, it is the only place in our country with naturally occurring wild magnolias.

The climatic peculiarities and geographical position of the Southern Kurils have made them the intersection point of several different floras and faunas typical for the Sea of Okhotsk, Manchuria, Norther Japan, and the adjacent Pacific Ocean. Along with representatives of various common «boreal» species of plants and animals, a number of «exotic» species occur here, typical for natural communities of Japan, China, and Korea, contributing to the immense biodiversity of this unique land.

Islanders and their neighbors

All in all, over 8500 known species of plants and animals occur in the protected territories of the Southern Kurils.

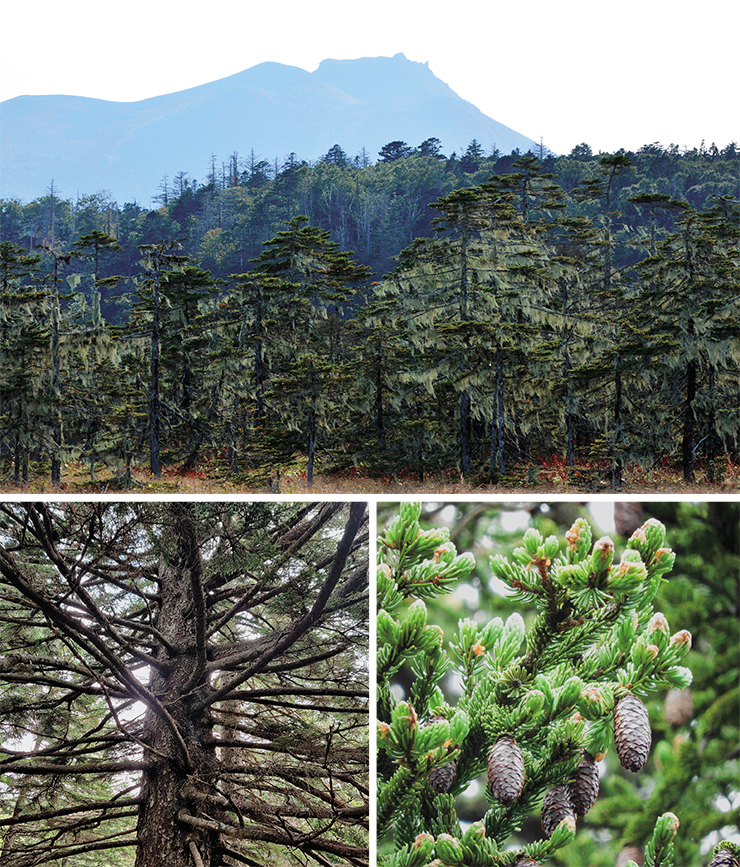

The flora of the protected territories is exceptionally rich: it includes about 2000 species, with almost a half of the diversity represented by vascular plants – the group which includes all higher plants except mosses. There are typically southern, East Asian species, such as deciduous arboriform vines, as well as northern species typical for harsh climates, such as firs (Abies).

A good example is the above mentioned Japanese big-leaf magnolia, a deciduous tree up to 17 meters (56 feet) tall with a pyramid-shaped crown and fragrant cream-white blossoms up 25–30 cm (10–12 inches) in diameter. Its main range lies in Japan and Korea. In Russia, the species is treated as endangered, and there is an ongoing effort in the nature reserve to restore the population numbers by germinating seeds and planting the saplings in the wild.

The Kurilskiy nature reserve, and the protected part of the Kunashir island in particular, with 60 % of its territory covered by forests, is a true refuge for rare plants. 83 local plant species are redlisted in Russia, including 9 species of vascular plants endemic to the island. The area is the northern limit of the ranges of such plants as the Japanese bigleaf magnolia (Magnolia obovata), Japanese maple (Acer japonicum), monarch birch (Betula maximowicziana), serrate-leaf chloranthus (Chloranthus serratus), Korean mulberry (Morus australis) and other southern species.

Slopes of hills, rocky outrcops and river valleys of the Lesser Kurils nature preserve, and the island of Shikotan in particular, which has a remarkably mild climate, are inhabited by 45 rare species of plants, including such well-known species as the large-flowered lady’s slipper orchid (Cypripedium macranthos), Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense), and pink rhodiola (Rhodiola rosea). In the Tserkovnaya cove, here is a relict grove of the Kuril larch (Larix kurilensis).

The Shikotan is home to a regional natural monument – the Phellodendron grove, covering 0.14 hectares (0.35 acres). It is a community of 109 recorded species of vascular plants, including 26 species of trees, dominated by the Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense, syn. Ph. sachalinense) and the Japanese yew (Taxus cuspidata), with trunks reaching a diameter of 90 centimeters (35 inches).

The flora of the area is equaled by its fauna, and birds in particular. The Kurils lie on one of the world’s key migratory pathways – the Kuril bridge, making its ornithofauna exceptionally rich and diverse. On the Kunashir alone, 288 species of birds belonging to 18 orders have been registered.

During seasonal migrations and summer movement, as well as during the winter season, one can observe waterfowl by the hundreds: loons, cormorants, gulls, petrels, and many others. The protected territories serve as nesting grounds to rare and endangered birds such as the osprey, white-tailed eagle, and white-bellied green pigeon; the Steller’s sea eagle is a common wintering species. The Kunashir has the highest concentration of one of the world’s rarest raptors – the Blakiston’s fish owl.

On the southeastern part of the Shikotan, in the Delfin cove, there are nesting and wintering grounds of many aquatic and semiaquatic birds, including the Manchurian crane – on of the least numerous crane species in the world.

The islands of Demina and Oskolki host summer rookeries of rare marine mammals: the Steller’s sea lion and the Kuril harbor seal (Phoca vitulina stejnegeri). Its coastal waters are home to the southernmost breeding population of the redlisted sea otter – a semiaquatic predator with the most valuable fur. There are also numerous cetaceans, such as the orca, the common minke whale, and the Baird’s beaked whale.

The diversity of vertebrates is not very rich. The largest representative of land mammals here is the Ussuri brown bear (Ursus arctos lasiotus). Many individuals of this species on the Kurils are pale-colored, which is hypothesized to be connected with the presence of polar bear genes in their genotype.

Other local predators include the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), sable (Martes zibellina), and lesser weasel (Mustela nivalis); there are some bats and rodents as well. The latter include the large Japanese field mouse (Apodemus speciosus), an insular species which only occurs in Japan and on the Kunashir, and the Shikotan vole (Myodes sikotanensis), an endemic of the Sakhalin region. Rare and endangered land vertebrates include reptiles, such as the Japanese forest rat snake (Euprepiophis conspicillata) and the already mentioned Far Eastern skink.

Freshwater bodies of the protected territory serve as spawning and juvenile fattening grounds of pacific salmon species, such as the pink salmon, chum salmon, salmon trout, etc. Some species, such as the malma trout, occur in local landlocked river-dwelling forms in addition to the pelagic form. A noteworthy example of the local salmonids is the Sakhalin taimen (Parahucho perryi), which can reach 2 meters in length and live up to 16 years. Overall, the ichtyofauna of the Southern Kurils is of «mixed» origin: it formed from the more southerly species of Hokkaido and the more northerly fish of the Kamchatka peninsula.

As for invertebrates, their fauna in the islands is rich, with over 5500 species known to date, but remains insufficiently studied. Each consequent research expedition yields species previously not recorded in the area. This is true about vertebrates as well.

The unique nature of the Southern Kurils, their peculiar flora and fauna deserve careful and wise treatment. Island ecosystems, isolated from the mainland, are especially vulnerable. They are easily disturbed, and the damage may be irreversible.

Protecting the unique landscapes and wildlife of Southern Kurils is by far not the only function of the reserve. The protected territories are a unique workspace for scientists from a variety of fields, ranging from biologists to geologists. For instance, in 2021, experts from Moscow, Kazan, Saint Petersburg and Vladivostok studied the microbial communities of hot springs and freshwater bodies, land-dwelling and aquatic invertebrates, explored forest ecosystems, and evaluated the anthropogenic pressure on the protected ecosystems.

Beginning from 2018, the numbers of tourists visiting the Southern Kurils increased fourfold. In 2021, over 3 thousand visitors walked the trails of the protected territories of the Kunashir. Workers of the nature reserve are actively engaged in ecological education, especially in the Yuzhno-Sakhalinskiy district. This includes various exhibits, ecological lessons for preschoolers and schoolchildren, working with children in school-based camps and in the summer tent camp «Fregat». The website of the nature reserve publishes fresh news and interesting facts about the unique nature of the Southern Kurils.

References

Barkalov V. Yu., Eremenko N. A. Flora of the nature reserve “Kurilskiy” and the nature preserve “Malye Kurily” (Sakhalin region). Vladivostok: Dalnauka, 2003. 285 p. [in Russian].

Martikhin E. K., Abdurakhmaniov A I. By a volcano’s side. Yuzhno-Sakhalinst, 1990. 38 p. [in Russian].

Red Book of the Sakhalin region. Animals. Moscow: Buki Vedi, 2015. 252 p. [in Russian].

Red Book of the Sakhalin region. Animals. Kemerovo, 2019. 351 p. [in Russian].

Zhuravlev Yu. N. The Kuril diary. Vladivostok: Dalnauka, 2001. 358 p. [in Russian].

Materials on the natural objects and flora of the ature reserve “Kurilskiy” and the nature preserve “Malye Kurily” was prepared by E. V. Linnik, the deputy director of research; materials on the animal world were prepared by S. Yu. Stepanov (engineer)