Spirits behind a Museum Curtain

The word “museum” usually implies large halls with polished floors, inevitable slippers at the entrance, and cool brilliance of brightly lit stands and showcases. This makes the contrast striking — you see a small room showing the interior of a Khanty house, and the open exposition creates the effect of presence, of real penetration into the culture half-forgotten and even unknown to many people...

Sherkaly is a national settlement in the north of the Oktyabrsky region of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug. It is located on a high steep bank over the Ob. Its history is long — it is older than four centuries. Even in old times it was considered to be a small settlement (there are fewer than one and a half thousand dwellers). A traveler can be amazed to see a snow-white church — a monument of the beginning of the last century, a modern Palace of Culture, an archaeological monument — the site of an ancient settlement named Sherkaly, and the old wooden mansion of merchants Novitsky…

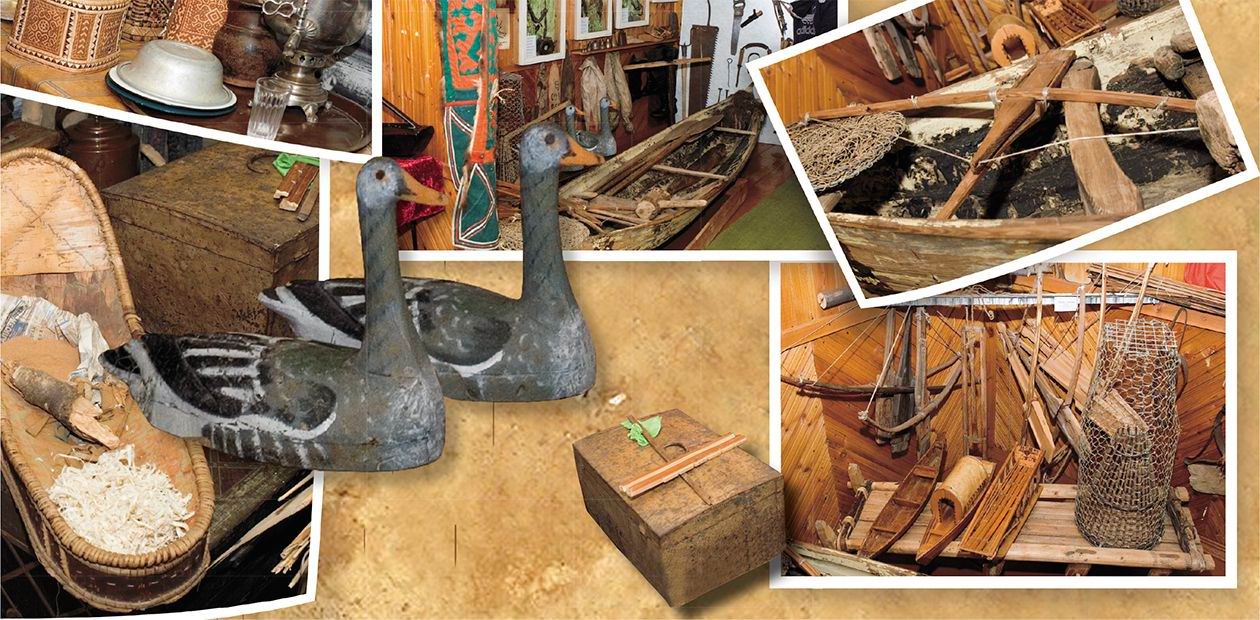

And suddenly (or, maybe, quite naturally) you see an ethnographic museum located in an ordinary loghouse (called “izba”). Visitors are often astonished by this, so they ask, “Where is the Khanty house (“chum”)? Archaeological digs show, however, that beginning with the early Iron Age settlements of the Low and Middle Ob Region sometimes had log houses. Besides, some dwellers of the ancient Sherkaly site were fishermen, who didn’t have domestic deer. Therefore, they did not have to move after their herds in search of food or pastures and could afford to have a settled life.

It has taken the Sherkaly Museum twenty-three years to grow from a schoolroom of local lore studies into a cultural center of the settlement, going beyond the scope of an ordinary exhibition. Now there are almost a thousand exhibits, and the museum has more than a thousand visitors every year… These are only figures, but they show a lot: laborious collecting, describing, placing the exhibits, tending to them, and organizing major ceremonial festivals.

Many exhibits of the Museum — including the oven for baking bread and the ancient flinty gun — are still usableIn the museum yard, visitors see a log barn on high carved poles and a clay oven for making bread. Judging by ash and soot traces, the oven is not only an exhibit; it is still used to bake bread.… The location of the oven is not accidental: the Khantys usually divide the house into a man’s half and a woman’s half; the area at the entrance — inside and outside the house — is traditionally considered to be the woman’s half. This is where the woman has her workplace. The bread oven is made by the woman herself. The woman also makes a chuval, which is something like a fireplace or, more exactly, a half-closed clay hearth. It can be seen in the right corner of the museum.

Chuval is something like a fireplace or, more exactly, a half-closed clay hearth with an obligatory vent leading outside (the chuval was not stoked “black”, that is, it had a chimney). Giving a lot of heat and light, it served mostly to heat the house and cook food. On the open fire one could broil, cook, and dry clothes; it was also the abode of Nai-Anki (Mother Fire), one of the spirits worshipped by the Khanty. It was very important not to allow the fire to “die”: it was considered that otherwise misfortunes awaited the family. All peoples have this attitude to fire, both in the north and in the southHere, in the woman’s part of the house, there are birch-bark pots and pans, which are warm not only to the touch, but also in appearance. Northern people consider the birch to be a sacred tree, and birch-bark things play an important role in the everyday life of North aboriginals. The birch-bark pattern, its meaning, and the techniques — these are a separate theme. The ornamental pattern on each casket — no matter how simple it may seem — is a story about the surrounding world “told” with the help of symbols. Each of these birch-bark articles not only belongs to household utensils, but is also a small “cultural monument”, a view on the world expressed by the people and by a certain craftsmaster.

When the Khanty began using iron plates and dishes, it was very expensive, and they had to pay entire fish carts or bales of fur for them. Still, people purchased iron dishes. However, most dishes, such as vessels of various sizes and shapes, woven baskets, and caskets, were made from birch-bark, a convenient and accessible material.Nobody knows how many of such things were made by Russian craftsmaster Agafya A. Voldina. The pattern-making technique by scraping that she used has already disappeared in many settlements. It is a pity, because such ornaments on birch-bark, made without a preliminary pattern, are practically eternal

The most beautiful, delicate and fine patterns decorate cradles. Symbolic patterns scratched on cradles contain various incantations to protect a sleeping baby against evil spirits or, as they say now, “against negative influences”. There was usually only one cradle in the entire house, which “remembered” all babies in the family. The Sherkaly Museum has such a cradle.

A birch-bark cradle was usually made in advance. People tried to protect the baby even before the birth: it was believed that before the baby had teeth of his own or before he smiled at his mother, he did not belong to the world of people and any evil spirit could take him away. The cradle that later became an exhibit in the Sherkaly Museum has a round plane stone resembling a coin sewn into it and serving as a mascot. And the parents’ efforts were not in vain: five babies, one after another, grew up in this cradle, small as it is at first glance.

The cradle bottom was covered with a thin layer of powder made from decayed red birchwood grown on a bog. If this powder became wet, it was not thrown away but collected. In spring, on April 7, Crow Day, the used powder was taken somewhere to the end of the village or to the forest edge and then emptied on a stump, while people said, “Let girls be born, let boys be born”.

It is usually still cold at this time, and it was considered that the crow — one of the first spring birds coming — would warm its feet on this powder.

This respectful attitude to the crow is not accidental: since the old times the Khanty have considered this bird the protector of women and children.

A boat called kaldanka occupies almost the entire length of the room. It reminds us of one of the main Khanty businesses, i.e. fishing. As for the nettle net, it was not designed for fishing. An ancient gun — a hunter’s customary accessory — is hanging on the wall, attached fast to it. Even now museum exhibit is still in good working order.

This refers not only to objects of everyday use, but to things of the sacral world. For instance, representatives of this family still come to the sacred box, the dwelling-place of the family spirits, when something good or bad happens. Presents for the spirit, such as lengths of cloth or coins, should be put into the box. The initial function of the sacred tree with ribbons tied to its branches, standing at the entrance of the museum, is to be a “guide” between the world of people and that of spirits.

In contrast to the widely used boat called oblasok gouged out from a whole tree trunk, the bottom and sides of kaldanka were made separately (the bottom was made from cedar, and the sides from fir or aspen). Then they were sewn together with the help of cedar or pine rootstocks. After being caught, the fish were stunned with a mallet. The number of notches on its handle shows how lucky the fisherman was...

Very long tackle (a long pole with a plummet in the middle and a net in the form of a sack at the end) was used for fishing whitefish and burbot.

All people fish, but not all fishermen are lucky. Lucky fishermen tried to mark the plummet in some way, not to be lucked out. For instance, the stone exhibit of the museum has a “herring-bone” pattern. If a fisherman could no longer fish because of his bad health or old age, he never gave away his mascot to his neighbor or his friend, he gave it only to his heir. If a fisherman had no heirs, he took the plummet to the so-called bethels, where he left it forever

After visiting such “provincial” museums, instead of being exhausted and tired of impressions, you feel that you have been to a fairy-tale or have revisited your own childhood, and that you were rather a guest here than a visitor. So you return home — “to the city bustle and car flow”, but you are different now. You rather feel than know who you are and where you are from.

The nettle hang-net made with the help of wooden needles was used by hunters to catch ducks, and many of them. In 1953, however, this duck catching was prohibited.Firearms appeared here in the XVIIIth century. The museum gun was used for shooting up to the middle of the past century. Even now it is still in good working order. It took no less than three minutes to charge such a gun — when hunting a bear or a glutton this is too long. Hunters also had to carry a powder-flask, shot sacks, and measuring rods. The hunter never forgot to take the good old bear-spear. There is a picture in the Sherkaly Museum which shows hunting with a bear-spear

Our guide is Natalia V. Kryukova, the museum curator:

“Each Khanty family had family spirits. Behind the curtain in a box, there is a spirit whose name is translated as the God of Spring and Fall Squirrel. As presents for him, one should put cloths (to cover his horse). Since there was shortage of cloth, people put shawls or lengths of fabric, and wrapped a coin into them.

It should be noted that the Mid-Ob Khanty tried not to depict spirits. Thus, there is no idol in this box. The spirit exists, but it exists in our imagination. It is just here. Women are not allowed to approach the box with spirits. So, naturally, if the women who work in the Museum have some work to do in this corner, they ask men to do it. This box is still “working”, and representatives of the family who live here come to the museum at least twice a year to worship the spirits. This is how the family is protected.”

Even the sacred box with spirits still serves its original purpose“Nothing happens accidentally in life. This box with spirits appeared in our museum first. When we were schoolchildren and came here on an excursion, it was already there, behind the curtain. And then I came here — to look after it. And the spirits, in turn, protect me.”

This publication is based on the materials collected during the journey “following in the footsteps” of the Second Kamchatka Expedition (1733—1743). The editors would like to thank the Khanty-Mansiysk State Museum of Nature and Man and its director L. V. Stepanova for allowing them to repeat one of the routes of the Great Northern Expedition within the framework of the symposium “Three Centuries of Yugra‘s Academic Investigations: from Mueller to Steinitz” (September 2005).