Vasyganskiy nature reserve: between land and water

The first ten words returned by an associative dictionary by the query “swamp” are quite telling: “frog, mud, water, forest, reeds, quagmire, quickmud, swamp, green, stench, peat”. Various folk proverbs agree: “Where there is a swamp there is devil”, “you cannot build a mill in a bog”, … God-forgotten places, refuges of evil spirits and monsters – bogs, fens and swamps have been called a variety of unflattering names since the beginning of time.

Why do people have such a strong dislike for wetlands – is it because of simple ignorance? People are unaware of the intoxicating smell of marsh Labrador tea in the sun of early fall, the sparkling of cranberries scattered in moss like a torn string of beads, and mushrooms siting here and there, like caps like golden coins… People don’t know the ease of breathing the air of bogs, washed by the fog to absolute purity, the softness of the taste of its clean cold waters the color of black tea, filtered by thousands of years worth of peat…

There are different ways, and different angles one can look at wetlnds… Guy de Maupassant, a French novelist and a passionate hunter, wrote: “mires are a special world on Earth, unlike any other; it exists following its own laws, it has its own inhabitants and vagrant visitors, its own voices and noises, and most importantly, its own mystery”. Blyam the Frog, a character of a fairy tale by V. Krotov, calls wetlands his home, as it is “ready to accept everything, and nothing will disrupt its calm… It provides a cozy home and good food to its ihnabitants… the MIRE, it sparkles with dew in the morning!”

Love Eternity reigning in mires,

Their powers never deplete.

Grassy lands never yield to the fires,

Smallest thickets will stand up the sleet.

Aleksandr Blok (translation by Viktor Postnikov)

Places where no man has set foot are becoming vanishingly rare on Earth, but the Vasyuganskiy Nature Reserve is, without doubt, one such place.

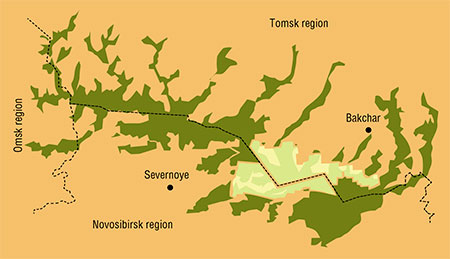

The Vasyuganskiy Nature Reserve (or Vasyuganskiy Zapovednik, the Russian term to denote territories of the highest protection status) was created in 2017 for the purpose of protection and study of the Great Vasyugan Mire – the largest mire not only in the Northern Hemisphere, but on the whole planet. The wetland, named after the river Vasyugan, a left tributary of the Ob, is situated in the middle and south of the West Siberian plain, in the taiga and forest-steppe zones.

The Vasyugan Mires began to form after the recession of the glacier during the last Ice Age, about 10 thousand years ago. First, 19 primary isolated wetland areas formed in its flat hollows, which then gradually merged into one. Even now, the system is actively extending with continuous bogging processes along the periphery, which add about 800 hectares to its surface area every year.

Structurally, the Great Vasyugan Mire is a mottled mosaic of forests, wetlands, and transitional biocoenoses, which differ significantly in its northern and southern parts. Forest communities occupy a relatively small area and are connected to river systems. Wetlands are extremely variable: from eutrophic fens fed predominantly by groundwaters to raised bogs which only get their water and minerals from the atmosphere as dust and precipitation, as well as numerous transitional types, which include treeless marshes, fens and bog hollows, as well as forested swamps and bogged forests.

The high variability of the landscapes here results in a great variety of peat deposits and vegetation types, connected mainly with different levels of humidity, salinity and acidity/alkalinity of soils.

The southern edge of the Great Vasyugan Mire serves a natural border preventing the introgression of northern species into more southerly regions. At the same time, the area serves as a major transitional hub for thousands of birds during their seasonal migrations in the spring and fall. Every year these trans-Palearctic species, whose ranges are often fragmented, fly great distances along the Earth’s meridians.

The Vasyugan Mire hosts significant populations of threatened wetland species of plants; a variety of game and furbearer species thrives on its territories. Thousands of hectares of truly primeval nature of the Vasyugan Mire are a sort of a reservation for all sorts of organisms, especially species typical for wetlands as well as rare and threatened species.

Orchids in the moss

The Vasyuganskiy nature reserve is one of Russia’s newest zapovedniks. Its great territory, remoteness from human dwelling and low accessibility complicate the organization of field research. It is impossible to cover the whole territory in the foreseeable future, so the studies began in 2020 from establishing a number of key model plots. In the first year, researchers of the reserve performed an inventorying survey of all land vertebrates and higher plants and created a map of the Verkh-Tartas plot in the southwestern part of the reserve. This territory, situated in the north of the Novosibirsk region, occupies over 36 thousand square kilometers (about 14 thousand square miles).

The results of the first surveys have allowed improving the existing data. According to the surveys, the flora of higher plants of the area includes 282 known species, which is a much higher number than previously assumed. Earlier surveys had discovered over 240 species of higher plants (including 132 species of vascular plants), with 26 rare and threatened species.

The results of the first surveys have allowed improving the existing data. According to the surveys, the flora of higher plants of the area includes 282 known species, which is a much higher number than previously assumed. Earlier surveys had discovered over 240 species of higher plants (including 132 species of vascular plants), with 26 rare and threatened species.

In eutrophic (nutrient-rich) hollows, where groundwaters saturated with minerals come close to the surface, vegetation is usually very rich. They host such wetland giants as cattails (Typha latifolia) and sweetflag (Acorus calamus), as well as a variety of sedges (Carex spp.), reeds, feather mosses and other water-loving species. As peat accumulates as the result of incomplete degradation of organic matter in conditions of excessive wetness and lack of oxygen, eutrophic hollows gradually turn into oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) raised bogs, which is the prevailing type of wetlands here. The process is very slow: peat deposits grow by just one millimeter per year.

Sphagnum mosses are the key peat-forming plants: Sphagnum fuscum, which is red-brown in color, Sphagnum magellanicum, a pinkish or reddish-tinted species, as well as bright-green Sphagnum angustifolium, etc. These mosses form a fuzzy patchwork of color on the surface of transitional mires and raised bogs. They produce large amounts of organic acids and phenolic compounds, which acidify the soil and halter seed germination and proliferation of various microorganisms.

Perennial dwarf berry shrubs are abundant in the peatbogs, such as cranberries (Oxycoccus palustris, or Vaccinium oxycoccos), lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and blueberries (Vaccinium uliginosum). Other common plants include the marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre), used as expectorant in folk medicine, and two species of sundew (Drosera), an insectivorous plant, which uses its unconventional feeding method to compensate for the lack of nitrogen and minerals typical for peaty soils. There are about fifty medicinal plants in the Vasyugan Mires, notably the marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), known for its anti-inflammatory and fever-reducing action and used in the treatment of joint pains, and the well-known valerian (Valeriana officinalis).

There are relicts of glacial and interglacial ages in the Vasyugan Mires, such as the cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) and dwarf birch (Betula nana). Another example is the scorpion moss (Scorpidium scopioides), which sometimes dominates the mossy stratum of communities of bog hollows. This conspicuous moss is sensitive to changes in environmental conditions, meaning that pollution, changes in the hydrology or acidity of the area can cause it to die off.

Forested areas of wetlands are home to various Siberian specis of orchids, including the large-flowered lady’s slipper orchid (Cypripedium macranthos), which prefers moist calcareous soils. Early in the summer, a visitor to the Vasyugan Mire can enjoy a rare and beautiful sight – whole beds of blooming lady’s slippers.

Legs and wings

The Vasyugan Mire has retained its primeval richness of wetland and taiga fauna typical for Western Siberia. The Verkh-Tartas district alone is home to 162 species of land vertebrates, with 20 of the species included in regional Red lists.

There are over 240 registered species of land vertebrates in the Great Vasyugan Mire, including 40 species of mammals. 41 of the species are included in various Red Lists. The abundance of food and lack of threats from humans provide for a high population concentrations of predators and herbivores alike. The most «inhabited» zones are edges of forest-mire complexes with numerous streams and lakes.

The mammalian fauna of the reserve is typical for southern taiga zones. Microtines make up over a half of the species richness, with a prevalence of Siberian and European species. Common species of mammals include the moose (Alces alces), brown bear (Ursus arctos), wolverine (Gulo gulo), Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica), stoat, or short-tailed weasel (Mustela erminea) and American mink (Neogale vison), an introduced species. There numbers of the sable (Martes zibellina) in the reserve are growing, and the species is expanding southwards into the forest-steppes of Novosibirsk region. Protected species of the territory include the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus), Eurasian river otter (Lutra lutra) and northern bat (Eptesicus nilssonii).

The situation with the reindeer is complicated. It is redlisted in the Novosibirsk region, while in the adjacent Tomsk district it is a legal game species. Raised bogs of the Vasyugan are believed to be inhabited by a localized population of these animals, however, its numbers are unstable due to poaching and predation. Detailed surveys and study of migration routes will help develop measures for restoring the numbers of reindeer across their original range.

In the 1960’s, there was an attempt to introduce the legendary Russian desman in the area – a primitive semiaquatic insectivore. This little animal occurs only in Russia and is very sensitive to the environmental conditions: it prefers quiet backwaters, oxbow lakes and lakes with stable water levels and abundant prey. However, after several years, the desmans were never encountered again, and the destiny of the introduced animals and their progeny in the Vasyugan Mires is unclear.

The avian world of the Great Vasyugan Mire is strikingly rich, compared to mammals: there are 185 recorded species from 15 orders. Various waterfowl stop here on the way to their breeding grounds up north; the common crane (Grus grus), whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) and a variety of waders (Charadriiformes) nest here.

The 13 protected species include the greater spotted eagle (Aquila clanga), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), snow owl (Bubo scandiacus), great gray owl (Strix nebulosa), etc. Upper reaches of rivers and lakes rich in fish are favored by ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) and white-tailed eagles (Haliaetus albicilla), which are both in the Regional Red List; the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), the fastest raptor in the world with a wingspan of about 1 meter (3 feet), was observed here in transit to its nesting sites up north.

The most mysterious inhabitant of these places is the slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris), which has been chosen to be the mascot of the Russian Bird Conservation Union (rbcu.ru). Only a few dozen individuals of this species remain in the wild. The only known nesting site of the slender-billed curlew was registered in the Great Vasyugan Mire in the beginning of the last century. Since then, only a handful of isolated individuals have been recorded in the wintering grounds. Hopefully, this small speckled bird still nests somewhere deep in the endless Vasyugan mires, away from human eyes.

The majority of the territory of the Vasyuganskiy nature reserve is still unstudied and still has a lot to surprise researchers. Further studies will help evaluate the share of the region’s biodiversity covered by the reserve’s protection, define the range and numbers of populations of rare and threatened species. Data from the ongoing surveying will help structure the territory into zones and establish eduational trails for «green» tourism.

Along with these tasks, workers of the nature reserve continue monitoring the wetland ecosystem, using a number of climatic and hydrological parameters of the protected territory. This will help to establish and assess threats to the well-being of the local biological communities and to fine-tune the efficiency the protection activities.

References

Inisheva L. I. Wetland Studies. Tomsk: TGPU. 2009. 210 p. [in Russian].

Semenova N. M. Protection of wetlands in Western Siberia // Ispolzovaniye I Okhrana Prirodnykh Resursov Rossii. 2017. N 1. P. 45–54 [in Russian].

Valutskiy V. I., Semenova N. M., Kuskovskiy V S. et al. On the necessity of protection of the Great Vasyugan Peatbog // Geografiya i Prirodnye Resursy. 2000. N. 3. P. 32–38 [in Russian].

Vartapetov L. G., Adam A. M. Landscape- and ecology-based peculiarities of the formation of the fauna of the Great Vasyugan Mire // Geografiya i Prirodnye Resursy. 2020. N. 1. P. 83–89 [in Russian].

The editors are grateful to the workers of the Vasyuganskiy nature reserve for their assistance in the preparation of this article: to T. Yu. Chernikova, deputy director of research, and E. V. Shumkina, deputy director of ecological education