The Various Colors of Jade

Even early humans, on the eve of evolution, desired to decorate themselves with ornaments made of rare materials (be it boar fangs, shark teeth, or ostrich feathers). In the Stone Age, as befits the epoch, colorful minerals were especially well-liked. Suffice it to recall a find from Layer 11 in Denisova Cave—a bracelet of dark green chloritolite, dated to about 30 000 years before present (Derevyanko, Shunkov, and Volkov, 2008). It seems that people of those days must have already developed an aesthetic perception of such things (“It really looks good!”). What is beyond doubt is that the decorations meant prestige and high status, as evidenced by a large body of ethnographic data. Another practical—from the perspective of traditional culture—purpose of colored stones is their magical effect as amulets, including for the treatment and prevention of diseases as well as hex and evil eye. Publications on these topics swarm all over the Internet, but in this case home-grown astrologers and healers illicitly exploit truly ancient beliefs

Due to its high technological characteristics, jade always stood out among prestigious healing products made of rare materials. In the times of antiquity, jade was called iaspis (possibly derived from the ancient Greek verb ‘heal’). It was only in modern times that the stone acquired its current name—in two versions: the Latin phrase lapis nephriticus (‘stone for healing kidneys’) first appeared in 1611, and the French word jade (from the Spanish term piedra de ijada, ‘stone against colic in the side’) in 1647 (Fersman, 1974).

Jade: a medicine or a symbol?

In China, the word used to call jade (yu) did not have any pronounced therapeutic connotations although many medical treatises mentioned, for instance, the use of jade plates for medical skin applications. The sacred, symbolic role of jade received much greater recognition. It was on the territory of Northeast Asia that the use of jade reached its peak throughout the human history. It became a highly respected and viable cultural symbol in many countries of the region (primarily in China itself). According to one of the authors of this article, jade was chosen as a symbol of supreme perfection by people of the Mongoloid race whereas the Caucasians chose gold (Tang Chung, 1998).

The comprehensive study of jade items, launched by Prof. Tang Chung as early as in the 1990s, inevitably brought him to the problems of transcontinental contacts and migrations, leading to the development of new ideas and approaches in both technological and aesthetic fields. These problems could only be addressed through the maximum use of the collected materials and with intellectual support from scholars who study jade cultures in the Asia–Pacific region.

Crazy for the red blue white and yellow…

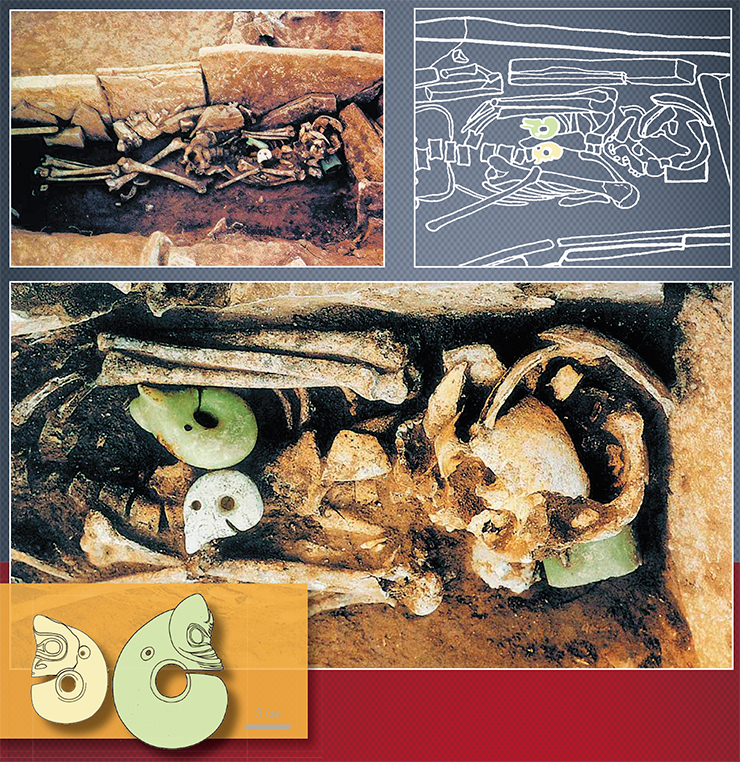

The earliest evidence of jade crafting comes from Siberia, from sites dating to the Upper Paleolithic (near the village of Malta along the Angara River). The tradition evolved further in the neighborhoods of Lake Baikal, an area that concentrates huge reserves of nephrite. Here, the Neolithic sites of the Serovo culture (5500—4300 BP) show a prevalence of tools made of green jade, and the Glazkovo sites of the Bronze Age (4000—3600 BP) contain mostly rings and discs made of white stone. However, the Glazkovo-type white jade ornaments spread in the Bronze Age over a much wider territory, from the banks of the Oka River in the Volga region to the basin of the Amur River, but it remains debatable whether they had come from a single center or had arisen convergent in different cultures.

Speaking about China, the earliest finds are attributed to the Neolithic cultures of Xinglongwa (8200—7200 BP) and Hongshan (c. 6600—4900 BP), which were discovered in Dongbei (more ancient jade ornaments, dating to 10,000 years BP, were recently found in this region, but they are few in number and not systematic). The most valuable items were made of yellowish-green jade, most likely from Xiuyan, the only field we know of in this region.

Meanwhile, the white jade items that were found in Heilongjiang are likely to originate from the cis-Baikal region, a possibility suggested as far back as in 1998 by Prof. Shinpei Kato. Contacts could have occurred along the banks of the Amur River. Ornaments made of white translucent jade are also found in Inner Mongolia, Jilin, and Liaoning, especially at early Bronze Age sites. It should be noted that the raw materials for jade manufacture were hardly of a local origin since no stones of this color have been found in Xiuyan.

A while back, Chinese scholars discovered that most of geochemical techniques (such as X-ray diffraction, infrared and Raman spectroscopy, etc.) cannot reliably distinguish between nephrite sources inside China. Russian experts came to more or less similar conclusions. Therefore, much importance is attached to visual techniques for identifying the color and transparency of the mineral on the accepted scale (the various shades of green and white predominate in the color scheme, but there also are yellow, azure, reddish, and even black stones).

Technology matters most

In recent years, a number of promising articles appeared on the study of rare-earth elements in nephrite by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Using this method, researchers were able to establish a difference in the concentration of rare-earth elements in nephrite from Xiuyan in comparison with other deposits in China. It seems that the same conclusion can be made about the Baikal nephrites. Data on stable strontium isotopes offer another promising instrument for zoning the sources of nephrite. Systematic application of these methods will create a complete picture for all nephrite deposits in the region and trace the transportation routes for the delivery of this valuable and, undoubtedly, practical material.

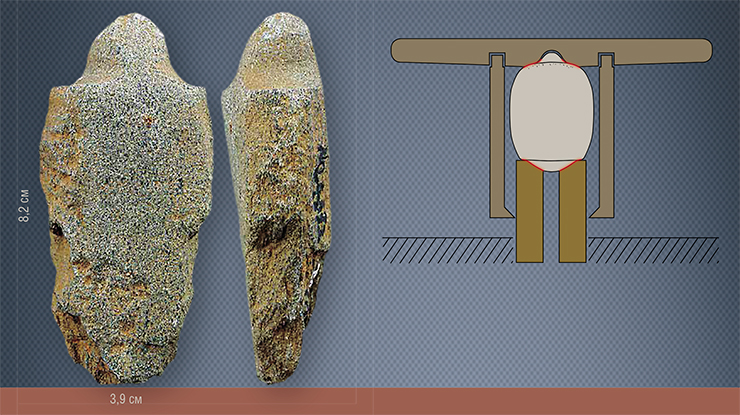

The accumulated data on the composition of the mineral resources can be verified using the technological approach developed by Prof. Tang Chung. He studied finished jade items and unfinished blanks by trace evidence analysis to restore the manufacturing process and tested his theory using the methods of experimental archeology. It turned out that as early as in the Neolithic, people used two main procedures (and devised the corresponding mechanisms) for the manufacture of rings and discs. One of these procedures, reconstructed by the archaeologist Sergei Semenov back in the 1950s, involves the use of the simplest available tools for the sawing and drilling of blanks. This technology was popular in most of the Neolithic cultures of Siberia and the Far East and in the northern regions of Manchuria. Another technology emerged in East China (Liangzhu culture, etc.) and gradually spread to most of East and Southeast Asia. The craftsmen used a boring machine of some kind with a base on which they fixed a blank; the base was set in rotation by means of a stone bearing. Hollow bamboo trunks must have served as a drill cutter (where there was no bamboo, one could have used large hollow bones, which were emptied of the core matter), which allowed for almost any diameter of the finished item. This “eastern” technology made it possible to mass-manufacture standard items, as demonstrated by excavations of stone-cutting workshops (e. g., at the Hac Sa (Heisha) site in Macau).

The two vast technological provinces interacted via an intermediate contact zone, which served as a venue for exchanging both raw materials and production skills. Thus, the stone ornaments from Chertovy Vorota Cave (7550—6880 BP) in Primorye, which is geographically close to the northern province, were manufactured using rotary mechanisms (machinery). The finds from the Ligaotu burial site (5000—4000 BP) in Inner Mongolia, despite its closeness to the Xinglongwa and Hongshan sites, include rings of white translucent jade made in the northern manner. The most original set of jade ornaments was found at Hamin (5500—5100 BP), also located in Inner Mongolia, relatively close to the former. Here, a single set of 30 items represents both traditions simultaneously.

The identification of this contact zone would allow a more detailed reconstruction of the contacts between the ancient cultures of Northeast Asia, and the new interdisciplinary methods would be helpful for further research of jade artifacts by Russian archaeologists (e. g., as applied to the problem of the origin of the Seima jades).

References

Alkin S., Morozov M., Zotkina L. Nephrite in the archaeology of Northern and Central Asia: New approaches to the interdisciplinary research of the problem of contacts between civilizations // The annual international academic conference of IASS 2017. Ho Chi Minh City: Vietnam National University. 2017. P. 54–64.

Komissarov S. A. Nefritovye den’gi: Interv’yu (Jade money: an interview) // Nauka v Sibiri. August 11, 2016. (URL: http://www.sbras.info/articles/simply/nefritovye-dengi) [in Russian].

Tang Chung, Tang Mana Hayashi. Comparative study of Neolithic jade technologies: from Chertovy Vorota to Northeast Asia // Multidisciplinary Methods in Archaeology: Newest Results and Prospects: Conf. Proc. Novosibirsk: Inst. Arkheol. Etnogr. Sib. Otd. Ross. Akad. Nauk. 2017. P. 306–317.

Tang Chung, Komissarov S. A. Nephrite cultures in prehistoric Northeast Asia // Vestnik NSU. Series: History and Philology. 2016. V. 15. N. 4: Oriental Studies, P. 5–10.

Tsydenova N., Morozov M. V., Rampilova M. R. et al. Chemical and spectroscopic study of nephrite artifacts from Transbaikalia, Russia: Geological sources and possible transportation routes // Quaternary International. 2014. V. 30. P. 1–12.

Zotkina L. V. Jade treatment results of experimental and technological studies of Transbaikalian raw material // Vestnik NSU. Series: History and Philology. 2018. V. 17. N. 3: Archaeology and Ethnography, P. 22–31 [in Russian].

Most of the photographs and other illustrations were provided by Prof. Tang Chung; the photos of excavations at the Hamin settlement site were provided by Prof. Ji Ping