China, diverse and eternal

Nearly all of our frequent and diverse trips to China have dealt with working on long-term research projects supported by the Russian Scienitfic Fund for Human Studies, and later the Russian Fund for Basic Research. Of all these brief travel notes, we will focus on some of our priority subjects…

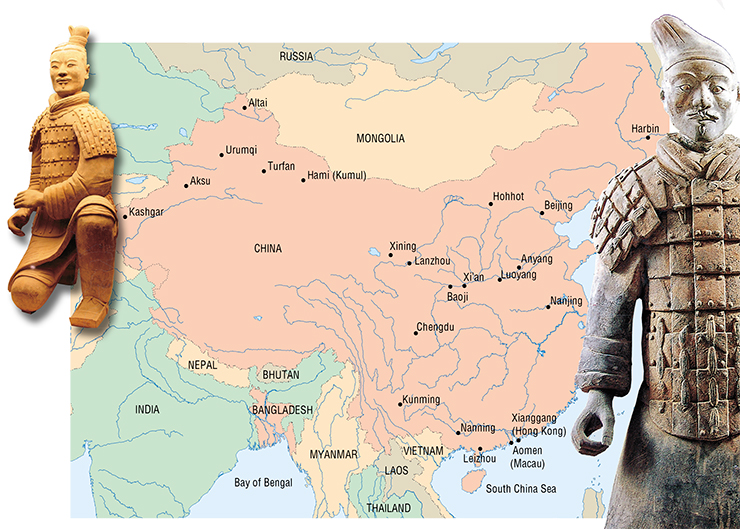

We must begin, of course, with Xinjiang, our southern neighbor. Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR) stretches along the western part of the Russian-Chinese border, which runs across the Altai Mountains. This part of the border, called the Siberian junction, is only 55 kilometers long; a leftover from the imperial and Soviet times.

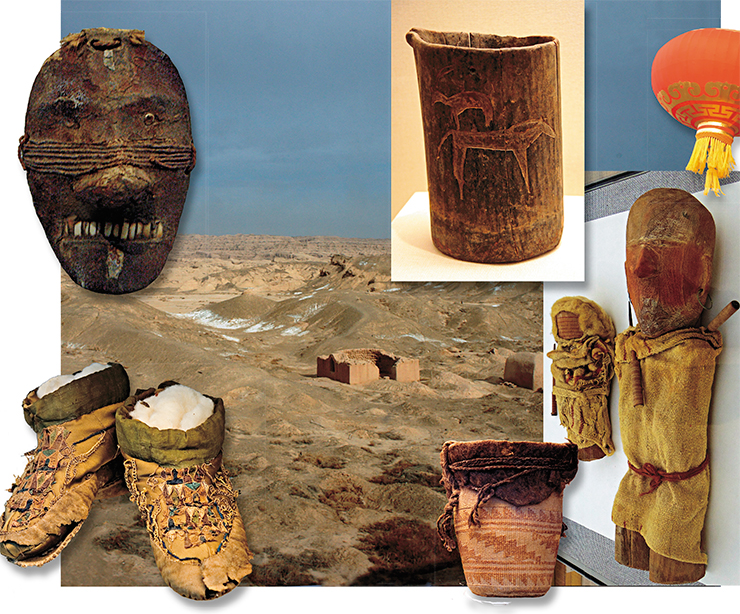

The population of the region, which has been changing a lot, has been in close contact with the peoples of Central Asia and South Siberia from the Bronze Age throughout the Middle Ages, and reconstructing their history separately can be misleading. Numerous archaeological finds are stored in museums throughout XUAR, and in its administrative center, the city of Urumqi, in particular. Artefacts from a Bronze Age burial site Xiaohe, discovered in the middle of the vast Taklamakan desert, are especially striking. The dry climate of the region played in favor of the preservation of organic materials – in this case, wooden utensils, woolen garments, felt hats, leather shoes and even remnants of food. There were wooden dolls and masks in some of the graves – portraits, obviously, albeit somewhat sketchy. But whose portraits were they? Long noses and round eyes suggest non-mongoloid origins of their prototypes; or perhaps, these were thought to be features of creatures from the netherworld?

Paleogenetic analysis identifies the population of the region of that time as Caucasoid with some Mongoloid admixture. Such analysis became possible due to another peculiar feature of the regions’ archaeology: the aridity preserved not only the burial structures and tools, but the bodies, too, which were naturally mummified. Some early Middle Ages mummies boast not only rich garments, but a range of parasites, too; for example, they were preserved in the braided hair of the famous Kroraina Princess (hygiene wasn’t a priority with the ancients).

Apart from the “capital” of the region, we visited a number or district and regional centers: Turfan, Hami (Kumul), Korla, Yining (Kulja), Altai, Aksu, Kashgar, and others: we have special memories from each of the cities. The town of Altai, for example, is a twin of our Gorno-Altaisk: devoid of tall buildings, sitting cozily in a narrow valley, with a swift mountain river running through it. It also has a nature reserve just a few hours away, with a strikingly beautiful deep lake, Kanas, in the middle.

The trip to Hami, apart from archaeology, had agricultural and gastronomical component. The thing is, this is the region from which, back in the Middle Ages, melons were brought to Northern China; this is reflected in the name of this culture: in Chinese, melon is still called “Hami pumpkin”, hamigua. We couldn’t leave Hami without trying this “pumpkin”! Indeed, melons are sold everywhere in Hami – they are beautiful, rather expensive, and quite tasty. But, with all respect to medieval melon growers, for introductory purposes, we would choose other varieties – the sweeter, more fragrant Turkmen or Fergana melons. The name of this sweet vegetable would be just as good – dayuangua, the “Fergana pumpkin”.

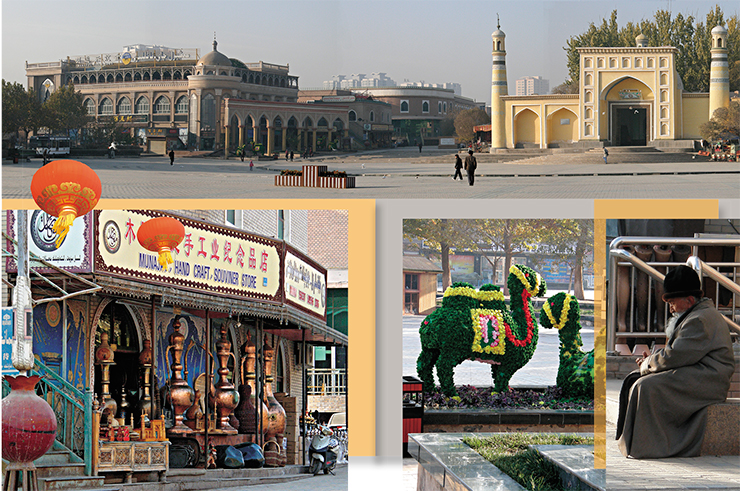

Our trip to Kashgar was also memorable – we literally had to stand guard for the only lady of our small team, tracked by hot stares of stubble-faced local guys. Virtually no one in Kashgar spoke Chinese. For instance, we were were trying to explain to a cab driver, that we needed the museum, and even showed it on the map – but in vain. Luckily, the driver heard the word «музей» in our discussion – naturally, in Russian – and it turned out that it sounds very similar in Uygur. Pure luck! It makes sense to prepare for our future visits to the Kashgar area by learning the basics of one of the Turkish languages.

The Central Plain – the cradle of the Chinese civilization

Another area which has been luring archaeologists and Orientalists, and Orientalist archaeologists in particular, is the land between Zhengzhou and Baoji, the famous Central Plain (Zhongyuan), where the Chinese civilization formedand reached one of its peaks.

Two ancient capitals, Luoyang and Xi’an (Chang’an), where the concentration of archaeological landmarks is beyond imagination, are especially remarkable. In 2002, construction workers in the center of the Luoyang city uncovered a relatively small (with a “mere” 600 graves) cemetery of the Eastern Zhou period (VI – V centuries B.C.), including a sacrificial complex complete with a carriage with six harnessed horses. Such a high-status, “6 h. p.” vehicle could only belong to the Celestial Emperor. In no time, the site was salvaged, “obstructive” buildings were removed from the square, their place was taken by a beautiful museum devoted to the unique find. The last 25 years saw dozens of magnificent state-of-the-art museums open throughout the country; many of those have their own research and restoration centers. These cultural centers are built on a large scale, intended for long-term research work.

Regarding Xi’an, the Qin Shi Huang mausoleum alone, with its terracotta army, has provided such a wealth of knowledge on ancient history, that it will take decades for science to completely apprehend it. The most intriguing thing here is not the numerous discoveries in this artefact-saturated land, with new major finds announced annually; it is the fact that they are secondary to the main grave, where the first Qin emperor is buried; numerous ancient manuscripts testify to the exceptional richness of the site (ceilings adorned with golden stars, seas and rivers of mercury on the floor, etc.). And this treasure hasn’t been excavated yet!

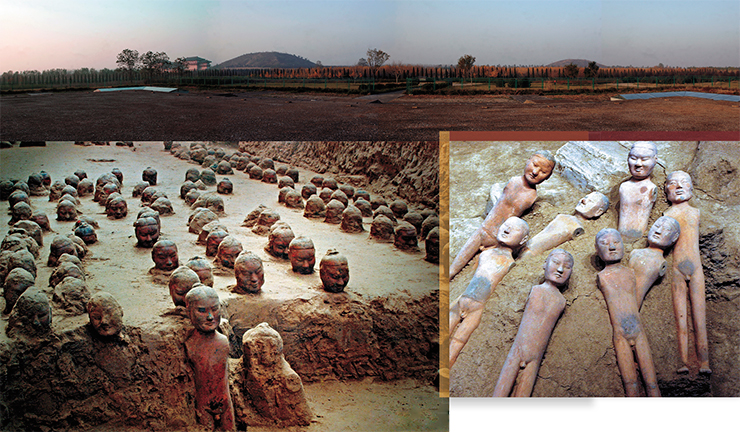

Apart from the main Qin cemetery, there is a constellation of Han emperors’ burial sites, with Yangling, the mausoleum of the emperor Jin-di (157—140 B.C.) being the only (incompletely) excavated one so far, out of eleven. This is where a whole “netherworld army” was unearthed, with over fifty thousand (!) ceramic figures of animals and humans, albeit smaller than life size (the scale is approximately 1:3). The army included infantry and cavalry, with hundreds of other figurines representing the palace servants of male, female, and neutral gender. The latter feature is especially fascinating. Sexual peculiarities, including those of the eunuchs, were carefully represented and thoroughly concealed with masterfully crafted, true-to-size clothing. Add the whole herds of pigs, dogs, and poultry! All this came from a single grave of a relatively “mediocre” Han ruler. There are also 18 emperor mausoleums of the Tang dynasty, located further, about 2—3 hours of driving away. Only two of them have been excavated, completely or partially, with the majority of finds displayed in the Shaanxi Museum of History.

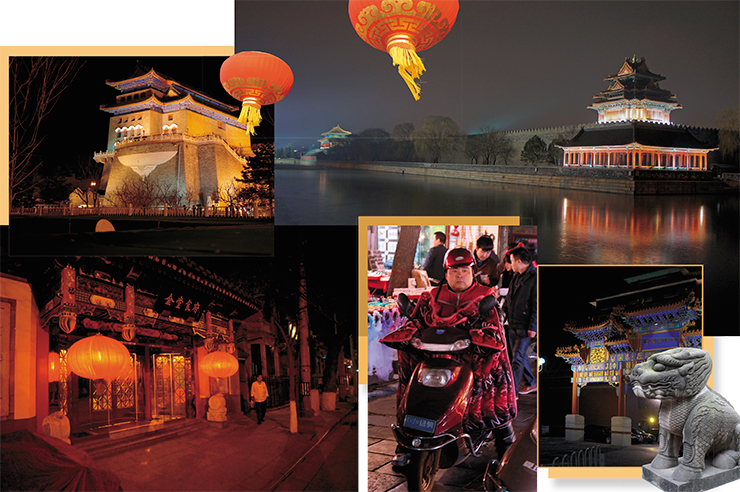

Beijing – yesterday, tomorrow, and today

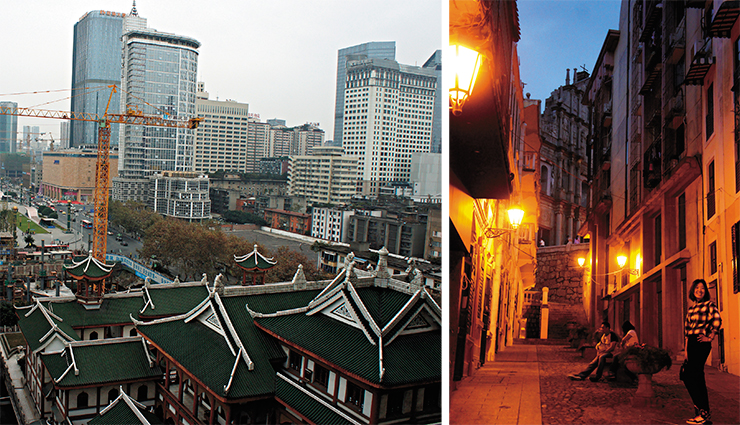

Without doubt, many journeys begin and end in Beijing – the city where the deep past and the pacing present merge into a unique unity. Squat mudbrick houses with clay tile roofs, huddled together along narrow streets, are flanked by mighty high rises with the all-too-familiar Stalin Baroque forms, diluted by intrinsically Chinese architectural traits. The high rises give way to glass-and-steel, hi-tech skyscrapers peaking above the immensely wide streets, by far exceeding anything you might see in a Russian city – with over ten lanes in each direction.

It is hard to find a proper epithet for the pace of change in the Chinese city. A couple of years ago, the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (our main Chinese partner) was flanked by one of the Hutongs, with its old streets, packed with traditional houses arranged in a square with a central courtyard – exactly the type of town houses which had made up the old Beijing. They were carefully dismantled, salvaging the clay tiles, and the vacated space was instantly occupied with new, mirror-walled buildings.

Like all major cities, Beijing is often congested with massive traffic jams. Along with regular cars, the city is filled with swarms of two- and three-wheeled carriages and all sorts of electric bikes, floating along – and often across – its streets and avenues in endless silent waves. Many of them are fitted with hulls and bodies of incredible designs, demonstrating the technical skills and sophisticated phantasy of their owners.

Speaking of traffic, stories of the lack of common traffic rules in China are completely true. One gets an impression that traffic lights, road signs and markings are purely decorative. Traffic officers, usually female, waving through the currents of traffic at intersections, are a saving grace. However, they work only in rush hours, attracting gawking foreign tourists and bored passersby from other provinces.

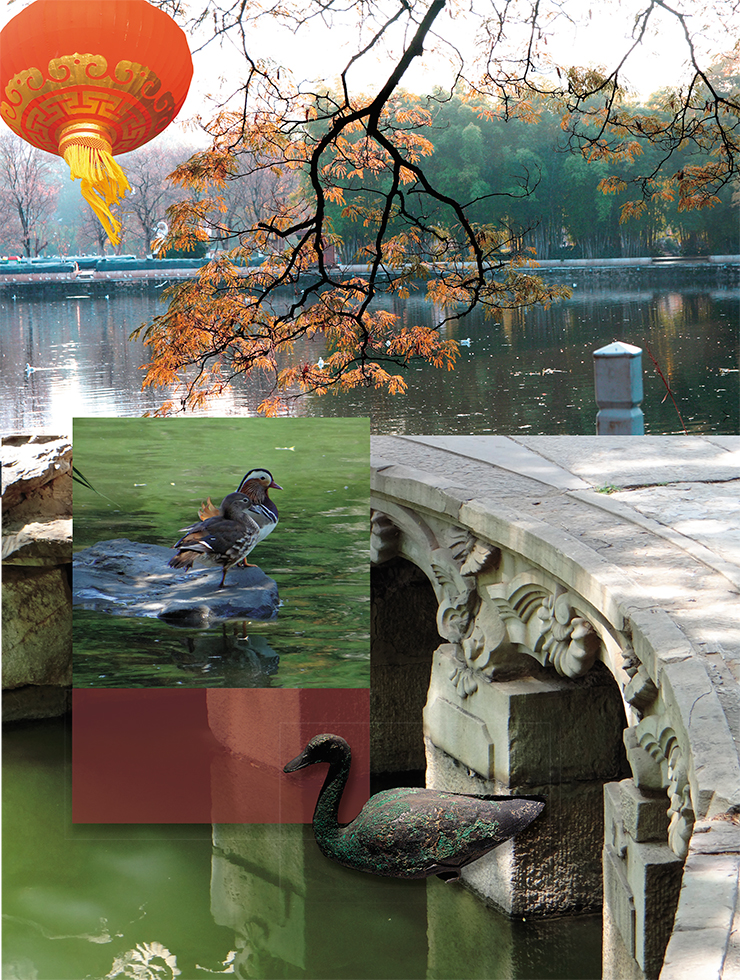

Like no other city, the capital of China is pulsing with its rich heritage of cultural layers. One of them is hidden in the depths of old parks with their meandering trails and curved outlines of artificial ponds and stone bridges hovering over the water. Colorful emperor carps surface among water lilies, sending light ripples across the deep water and swaying sleepy swans. All this, together with the painstakingly planned parkland architecture and sounds of living nature, put the observer into a contemplating state.

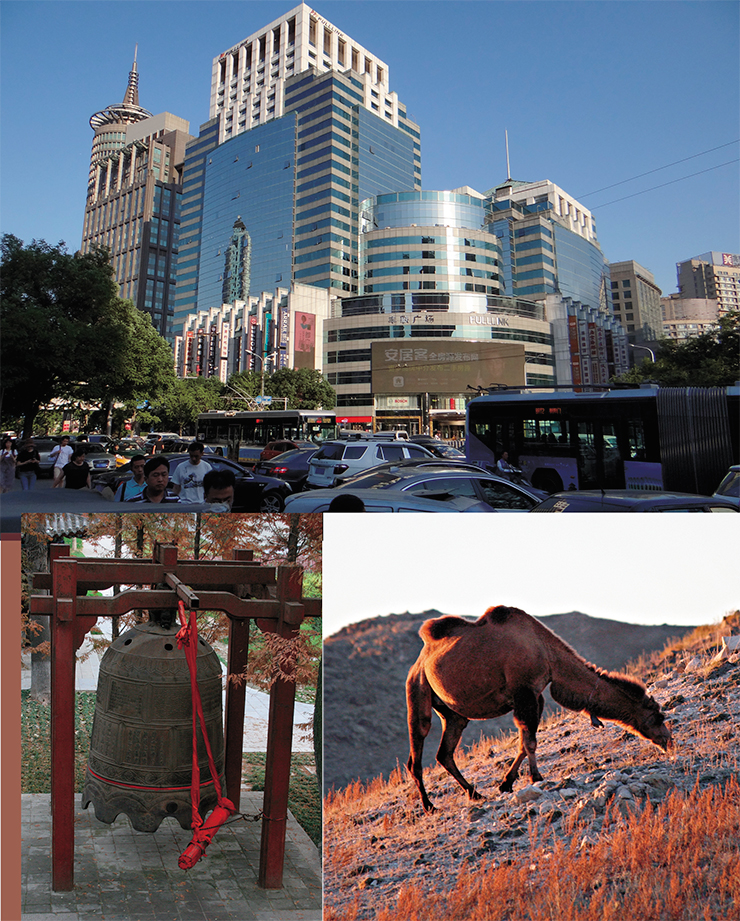

But another layer, predatory and dynamic, keeps us awake; it stays behind the armored glass of corporate headquarters, flowing through the vast show halls of modern expo centers, throbbing in the rushing economy.

Yet another layer is the unique, multi-faceted folk culture. This diversity is especially apparent in national districts. For instance, in Xinjiang, a suburban mudbrick house with a flat roof can stand next to a felt yurt, with a completely modern vehicle parked in the front and a couple of shaggy camels chewing something in the back, perhaps with an old carriage made of dry, shriveled wood. Camels roam free here and there, often in herds, grazing on the scruffy desert vegetation.

Here, one encounters crumbling mudbrick walls of ancient сaravanserais next to their modern concrete block counterparts. Even motor vehicles are often subjected to a sort of retro-upgrade: they are covered with colorful horsecloths and adorned with other equestrian artefacts typical for the local culture. The domes of the Muslim burial mazars look especially monumental against the background of modest earth and rock mounds of the Han graves.

The union of the Sky and the Earth

China’s multiculturalism, which was especially apparent in some historical periods, is more than evident in the cool halls of provincial museums of regional studies. Museums reflect the society’s interest in history of the country, and the real attention paid by the government to archaeological research and patriotic education of the population, as well. The latter is aided by vivid representation of the past in museums, and by museumification of the most important historical objects with high availability to tourists.

One of the most impressive examples is Ming Shisanling (Thirteen Graves) – an emperor’s necropolis from the Ming Dynasty (1368—1644), located 42 kilometers to the northwest from downtown Beijing, in a valley surrounded by mountains. The location was selected in the early XV century by the most competent fengshui experts of the time. The entrance to the valley, where the necropolis stands, is flanked by two mountains on each side: Longshan (the Dragon Mountain) to the east and Hushan (the Tiger Mountain) to the west; they serve as natural watchtowers. To the south and north, there are two more mountains connected to the cardinal points’ rulers – Zhuqueshan (the Red Bird Mountain) and Xuanwushan (the Dark Warrior Mountain), respectively. The position of the mausoleums in the valley is a reference to an important feng shui concept of “favorable cave”, a place traversed by “dragon veins” (longmai), i. e. underground energy flows. The Shisanling complex is especially interesting in that, being a quintessential point of funerary architecture, it has retained the most ancient, pre-Confucian traits of burial rituals due to the known conservatism and traditionalism of the Chinese society.

In front of the Changling mauso-leum, the emperor Zhu Di’s Yongle’ grave, there is a “spirit alley” – a slightly curved line, partly due to the terrain, and partly because of the adherence of its creators to feng shui and the traditional Chinese aesthetical cannons, which favor curved lines. The sculptures here are typical for medieval Chinese burial sites: columns, statues of bureaucrats, warriors, real and fantastic animals.

All tombs share a similar structure. Each contains an underground grave and aboveground structures: a pavilion housing stone turtle with a stele describing the achievements and beneficences of the emperor mounted on its back, a ceremonial hall for rituals, and a gate-tower, with a corridor leading to the grave.

The layout of the tombs demon-strates the new cannon of funerary architecture of the Ming period, characterized by a combination of aboveground structures with a square layout when viewed from above, with a round burial mound, while Tang and Song graves were surrounded by a square wall. The combination of round and square structures (square in the front, circle in the back) is an example of the traditional Chinese geometric symbolics, with the circle representing the Sky, the square representing the Earth, and the whole complexi being a symbolic union of the two.

There is a remarkable similarity between the layouts of the Shisanling burial complex and Beijing within the city wall. It is seen not only in the same architectural forms (gates, arches, and pavilions), but in their construction, position and scale. The “alley of spirits” is about 7.3 kilometers long, and the central walled part of Beijing stretches across 7.8 kilometers along the north-south axis. This feature of Ming necropolises is not exceptional; it originates from the emperors’ burials of the Tang dynasty, which copied the layout of Chang’an – the capital of Tang China.

The structure and contents of an underground tomb can be illustrated by the Dingling tomb of the emperor Zhu Yijun (Shenzong) (1573—1620). Excavations in 1956—1958 uncovered a massive cross-shaped tomb containing five halls with a total area of 1195 square meters (12863 square feet). Inside were the skeletons of the emperor and his two wives, with rich, gold-broidered garments, crowns made of gold, gems and pearls, golden ingots and jewellery made of jade, gold and gemstones; there were also golden and silver dinnerware, china vases, ritual vessels, headboards, etc. – a total of over 3 thousand items! Later, in 1959, amuseum was founded in the Dingling mausoleum, once the excavations were finished.

In 1961, the thirteen emperor graves of the Ming Dynasty, including Dingling, were included in the list of Special protection objects of China’s Cultural Heritage. However, during the cultural revolution, the Dingling tomb suffered serious damage: in 1966, the Red Guards burned the remains and destroyed many of the finds. With the arrival of the policy of “reforms and openness to the outer world”, restorations began. Since 1989, all archaeological works have been stopped in Shisanling, and in 1995, a museum of the whole site was established there. In 2003, the Ming emperor tombs in Beijing and Nanjing were included in the World Heritage list of UNESCO.

Visiting the mausoleums of the ancient and medieval China, one cannot help comparing them to the burials of rulers of the nomadic periphery. Thinking outside the immense presence of the Chinese empire, one notices the influence of the “barbarian” herder world in the shapes and structure of the burials, transcending the purely Chinese aesthetics.

The earliest images of bixie, a fantastic creature from the “alley of spirits” bestiary, are reminiscent of the Scythian griffon. Sculptures of those “spirit path” bear architectural and, apparently, conceptual ideas embodied in rows of balbals, which are found in steppe warlord burials. The Chinese tried to deflect these ideas, brought by devastating raids of swift nomadic horsemen, by all sorts of walls, including the Great Wall; centuries later, after thorough rethinking by the Chinese, these ideas rolled back at the nomads, and, having fallen onto the fertile soil of local traditions, bloomed and materialized in a medieval stone culture, albeit simpler and more compact, like the life of the nomads themselves.

China has gone through a series of periods when the empire was, like a sponge, soaking up cultural and technological advances of its neighbors. Revealing and studying such impulses, based on the richest written history of China, open immense research perspectives, putting us closer to understanding and reconstructing the beliefs of the long vanished nomad societies, including those of Siberia, and to truly understanding and appreciating the ancient multiculturalism heritage. But, say, this is a completely different story…

References

Kojanov S. T. Five walks along Beijing: 2nd ed. Novosibirsk: NSU, 2014. 237 p. [In Russian].

Komissarov S. A., Soloviev A. I., Kudinova M. A. Attack to the South: Urumqi – Aksu – Kashgar // Vestnik of Novosibirsk State University. Series: History, Philology. 2015. V. 14. N. 10: Oriental Studies. P. 278–282 [In Russian].

Komissarov S. A., Soloviev A. I., Kudinova M. A. To the investigations of Shisanling – funeral and memorial complex of the Late Medieval Ages in China // Vestnik of Novosibirsk State University. Series: History, Philology. 2018. V. 17. N. 4: Oriental Studies. P. 46–58 [In Russian].

Komissarov S. A., Khacha-turian O. A. Mausoleum of the Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi. Novosibirsk: NSU, 2010. 216 p. [In Russian].

Kravtsova M. Ye. World Artistic Culture: A History of Chinese Art: Study Guide. St. Petersburg: Lan’; TRIADA Publishing House, 2004. 960 p., ill. [In Russian].

Soloviev A. I., Komissarov S. A., Solovieva E. A. Development of the statuary sculptures on the territory of Xinjiang // History and culture of medieval peoples of steppe Eurasia: Proceedings of the II International congress on the medieval archaeology of Eurasian steppes. Barnaul: ASU Publishing House. 2012. P. 218–220 [In Russian].

World Heritage Sites in China / Ed. by Guo Changjian. Beijing: Intercontinental Press, 2007. 284 p.

Shisan ling [十三陵]=Ming Tombs / Ed. by Hu Hansheng. Beijing: Beijing meishu sheying chubanshe, 2004. 141 p. (In Chinese & English).