Glorious Baikal... The Omul Barrel

Royal dynasties deserve esteem. Pop-star dynasties evoke a smile of understanding. What would you say about a dynasty of ichtyologists? Lyubov Sukhanova is a true ‘blue blood’, ichthyologist in the third (!) degree. Her mother’s parents were ichthyologists; her father’s father was an amateur fisher. After graduating from a university in Kaliningrad, her parents moved to Lake Baikal. Since then, for almost 40 years they have been studying Baikal omul. Thus, her love for science and Baikal Lyubov inherited from her parents, it has been ‘imprinted in her genes’.

The depths of Lake Baikal keep many mysteries. Being captivated by them once, you are caught forever by the lake, all other things will seem humdrum and dull to you. Baikal becomes your fate and, as is well known, there is no escaping fate.

As a small girl, I used to say, “I don’t want to be an ichthyologist!” I knew what I was talking about; this decision was not based on hearsay. My parents were ichthyologists and they often took me to ichthyologic expeditions, their team observed the spawning of Baikal omul. I knew how menacing the run-high Baikal could be, how bleak it was staying on an autumn night in the boat when the motor was broken, how uncomfortable a fisherman’s wintering could be. Indeed, I did not become an ichthyologist; I studied molecular biology at the Chemistry and Biology Department of the University. Nevertheless, the fate brought me back to Lake Baikal and the famous Baikal omul. It was the fate’s goodwill. Baikal whitefish and Baikal omul, as one of the representatives of whitefish, are exciting objects for studying evolutionary processes occurring in the lake in general and in the family of whitefish in particular. The biology and ecology of whitefish have been studied on Lake Baikal for more than half a century.

It will not be an exaggeration to say that the Baikal omul is as widely known as the lake itself. For many people these two notions are inseparable and denote something unique. However, few people know that, following the contemporary scientific classification, Baikal omul is a variety of the Arctic omul, which teems in the Arctic Ocean.

For long it was supposed that the ancestor of the Baikal omul came to Baikal relatively recently (of course, in the geological timescale). Thus, the Baikal omul is so much like the Arctic omul. This distinguishes the omul from the other lake inhabitants having a long Baikal-based pedigree which underwent substantial evolution and turned into different, endemic species that are not met elsewhere. It is noteworthy that the Baikal omul was called Salmo migratorius in the first systematic description (Georgi, 1775). Then it was renamed several times until it got its present official name Coregonus autumnalis migratorius (Berg, 1932). Since then the name has secured to the omul. As K. I. Misharin (1958) wrote, it corresponds most closely to “its systematic position and geographical distribution”, as a subspecies of the Arctic omul that got in Baikal through the northern rivers.

But the opponents of this hypothesis believed that the ancestors of the Baikal omul inhabited the water reservoirs that existed here long before the lake was shaped in its contemporary form. However, the arguments of both sides were indirect. Many researchers considered the appreciable morphological similarity of the Baikal omul and the Arctic omul as a direct evidence of their close filiation. Thus, the hypothesis on recent penetration of the omul in Baikal became official. Nevertheless, some morphologists still believe that this similarity is not close enough and the cognation is disputable. As a result, the discussion of the origins of Baikal omul has lasted for more than two centuries.

The parentage of the Baikal omul is only one of a number of scientific problems concerned with Lake Baikal. If we abstract our minds from Baikal, we recall that the whitefish in general is the most advanced group among the salmon type fish. The most widely spread among them is the common whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus L.) inhabiting the rivers and lakes of North America and Eurasia. Whitefish varieties are distinguished by great morphological variability. But their exterior is primarily influenced by the specific habitat rather than the geographic location of the water reservoir they live in. Thus, sometimes researchers might find several different forms of the fish in a small lake, while on different continents they find populations whose exterior has very much in common.

One might think that the Baikal whitefish is nothing in particular. For more than 50 years it was believed that Baikal, like many lakes of the planet, is inhabited by only two forms of the whitefish species — littoral and pelagic.

The pelagic form is the Baikal lacustrine whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus baicalensis Dyb.) that spawns in the lake. The littoral form, lacustrine fluvial whitefish pyzhyan (Coregonus lavaretus pidschian Gmelin) not only spawns in the tributaries, but also spends there most part of its life (Skryabin, 1969). Scientists suggested that the niche of the pelagic whitefish forms living in the depths is occupied by the Baikal omul, the offspring and close relative of the Arctic whitefish that migrated to Baikal from the Arctic Ocean (Berg, 1932, 1948).

Later it was found that phenotypically the common whitefish in Baikal is as flexible as in no other water reservoir. The molecular phylogenetic analysis that enabled the reconstruction of the genealogical tree of the Baikal whitefish proved that the Baikal omul is nothing else but the proper whitefish, whose superficial resemblance to the Arctic whitefish is the result of adaptation to the specific habitat. Recalling that the Baikal omul is presented by three rather than one pelagic forms, we inevitably conclude that there are five (not two!) forms of common whitefish in the lake! In turn, each form is presented by several heterogeneous populations reproductively isolated from one another. The complex structure was formed by the Baikal species so that they could optimally use the food resources of the deep-water cold lake.

The greatest surprise is the relative juvenility of the complicated intraspecific structure in conjunction with the fact that the Baikal whitefish separated from the other representatives of the species about 1.8—3.4 million years ago, during one of the periods of high tectonic activity. It is established that there are no explicit genetic distinctions between the populations and even the majority of ecological forms of Baikal whitefish.

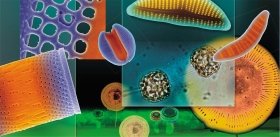

Apparently there should have been some circumstances that prevented long-term isolation of the groups in the lake. The most probable reasons are regular climate fluctuations due to the change of the Earth’s orbit parameters. From the change of the content of biogenic silica and the remains of diatoms in the Baikal sediments, one can distinguish about 30 periods of cooling and warming conditioned by astronomical reasons (Grachev et al, 1998; Karabanov, 1999). Such fluctuations occurred in the Pleistocene, Pliocene, and Miocene. During the Pleistocene the amplitude of the fluctuations was the greatest, even real glacial periods happened (Karabanov, 1999). The formation of glaciers in the mountains framing the lake was accompanied by dehydration, considerably lowered water level due to the reduction of the river run-off and even disappearance of some tributaries. The warming periods were characterized by reverse processes (Mats, 1993).

Since the reproduction of the omul and the lake whitefish occurs in the tributaries and the shallow-water bays on Baikal, the cooling periods led to severe changes in the populations, up to complete extinction of some of them. Subsequent warmings resulted in the regeneration of the whitefish but only as a new population structure. Thus, the existing populations could form not earlier than the end of the last cooling period, which, according to the Baikal ‘diatom chronicle’, took place not later than 11.3—9.5 thousand years ago. That is not much for the natural history of 10 thousand years, just a short blink of the evolution… But in this period the common whitefish turned into the Baikal omul, which is as unique as the lake that it symbolizes.