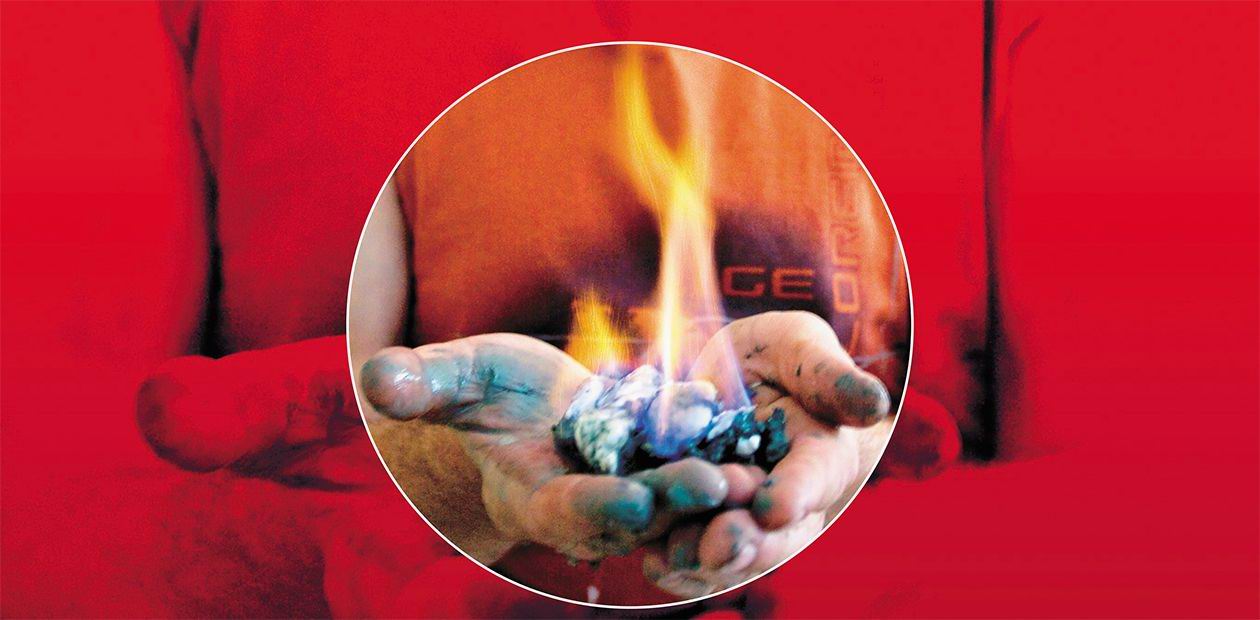

Lake Baikal: Fire and Ice

Electronic and other media are reposting a popular video where a truly Siberian fisherman creates fire from the ice of Lake Baikal in front of amazed journalists. A pillar of fire on the frozen surface of the legendary lake is a mindbending show, but it looks natural both for the locals and for scientists

The burning flare on the ice of Lake Baikal on February 1, 2017 was created by a fisherman engaged in industrial fishing in the Istominsk Bay, Kabansk district, Buryatia. The fire show is witnessed by reporters of the newspaper Kopeika. Video by Boris Slepnev

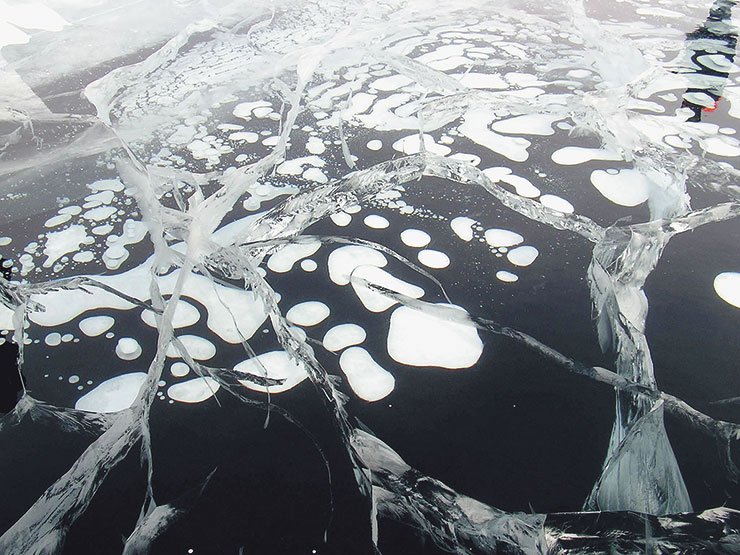

This video, which is now popular on the Russian web, could have been filmed 100 years ago by the outstanding Russian explorer and scientist Vladimir Obruchev, and these words of his could have appeared in the title frames: “Long before the cracking of ice on Lake Baikal, bare spots appear on its frozen surface. Local people call them proparinas (from the Russian word par meaning 'steam')... As soon as Lake Baikal develops an ice cover, when the ice is still very thin, large bubbles of air (gas) appear beneath the ice in the places of the future proparinas. If one breaks the ice deftly with a pick and sets a burning match to the hole, a bright flame will spring up, sometimes one fathom high, depending on the size of the bubble.”

Since the very name of Lake Baikal means “standing fire” in the Buryat language, people saw burning gas flares here since time immemorial. In the modern period, from the 17th century onward, a lot of travelers saw emissions of natural gas along the entire coast of Lake Baikal. In 1868, the Imperial Geographical Society even organized a special expedition to study this phenomenon.

Since the very name of Lake Baikal means “standing fire” in the Buryat language, people saw burning gas flares here since time immemorial. In the modern period, from the 17th century onward, a lot of travelers saw emissions of natural gas along the entire coast of Lake Baikal. In 1868, the Imperial Geographical Society even organized a special expedition to study this phenomenon.

According to recent data, the total amount of dissolved methane in the lake is more than 800 tons. To maintain this concentration, about 80 tons of gas must come into the lake each year (Granin et al., 2013). Moreover, Lake Baikal is the only freshwater body with enormous confirmed deposits of gas hydrates (discovered in 1997), a unique “preserve” of methane and water, with a bulk gas content of 150–180 units per volume! Gas hydrates are known to form at low temperatures and high pressures, and these particular conditions exist in deepwater areas of this fresh “ocean.”

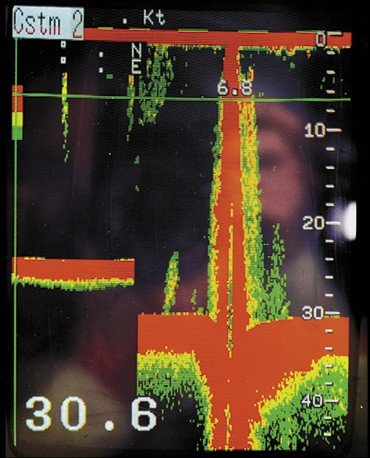

The methane that is constantly released from sediments in Lake Baikal is a product of the transformation of organic matter in deeply buried sedimentary rocks. Gas outlets are found both at large and small depths. The gas release is particularly intense in the Selenga River delta and its offshore strip (where the video was filmed). This area is known by a thick 7.5-km sediment layer with a high organic content. This organic matter had began to form here long before Lake Baikal became what it is today (Isaev, 2001).

A signature of Lake Baikal's deepwater areas is the massive manifestation of mud volcanism due to the large thickness of the sediments, tectonic features of the lake bottom, and modern seismic activity. The mud volcanoes closely resemble the ordinary ones in shape: they expel jets of liquid and gas, possibly tens or hundreds of meters high, but their only manifestation on the water surface is a cluster of bursting gas bubbles. It was near the mud volcano Malenky that a large gas flare more than 1000 m high was observed in 2011.

The intensity of gas release in Lake Baikal dropped considerably in the second half of the 20th century. The likely reason is the rise of the lake level after the construction of the Irkutsk Hydroelectric Station, which caused a decrease in the in-situ pressure and in the intensity of methane release (Granin et al., 2014). However, the methane concentration in the water column increased by a factor of 3 over the last decade. Some researchers blame this event for the catastrophic changes in the ecosystem of Lake Baikal, primarily the disease and death of the unique Baikal sponges, the so-called filter feeders. The reason is that sponges live in close symbiosis with microorganisms such as methanotrophs, which oxidize methane and its derivatives. An increase in the methane content, albeit beneficial for these microorganisms, may destroy the symbiotic community.

Here it is important to recall that there are large amounts of natural gas hydrates in the depths of Lake Baikal. These crystalline clathrate compounds exist on the border of phase stability, and even a small change in temperature and pressure (e.g., due to global warming) could lead to their avalanche-like irreversible breakdown with a release of huge amounts of methane. The consequences of such an event defy imagination.

The editors of SCIENCE First Hand thank N. Granin and O. Khlystov (Limnological Institute SB RAS, Irkutsk) for their help in preparing this publication

Translated by Alla Kobkova