Eight-Legged Soldiers

Myths and Conspiracy Theories around Tick-Borne Infections

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the lives of billions of people worldwide – by January 2021, more than two millions people had died, according to official figures; business shutdowns, national protectionism, and disrupted supply chains have hit the economies of all countries. One of the phenomena that always accompany epidemics and interfere considerably with the course of events is an avalanche of fake news and conspiracy theories. This time, however, they peaked to unprecedented heights, driven by modern media and social networks as well as politicians and beneficiaries, primarily pharmaceutical companies. As a result, an overall lack of awareness created a substrate for the most diverse theories to sprout – from utterly insane (spreading of the virus by means of an electromagnetic field) and speculative (chipping of people under the guise of vaccination) to very plausible ones (the pandemic as a pretext for the ruling elite to implement technologies for controlling people). All this is no joking matter whatsoever as cell towers are being destroyed and the campaign for a complete ban on vaccinations is gaining strength. Therefore, it would make sense to recall the rumors, suspicions, and theories that were spread around epidemics of other diseases, such as tick-borne infections

As far as the new coronavirus conspiracies and fake news are concerned – now it is too early to discuss them. We have too little reliable information because a detailed “postflight debriefing,” i. e., analysis of the causes, the course, and the outcomes of the epidemic, will only be possible in six months. It should be noted, however, that a trail of conspiracy theories also accompanied other sudden outbreaks of diseases attributed to organisms that cannot be seen with the naked eye – these events always create fertile soil for imagination.

A good example is the so-called natural focal diseases. Their causative agents exist in nature independently of humans, who serve as their casual hosts only. These diseases include infections transmitted by ixodid ticks. True, the “epidemics” of tick-borne infections have not gained so much notoriety as those of cholera or plague; however, they are perpetual, and they are expanding as hundreds of thousands of people worldwide fall ill every year with tick-borne borreliosis (Lyme disease) and tick-borne encephalitis.

The rapid spread of ixodid ticks in recent decades, along with the unresolved issues of diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases, gave rise to several very tenacious conspiracy theories. In short, they blame all these epidemics on scientists who are developing biological weapons.

The urgency of the tick-borne disease issue, which remains a concern for hundreds of thousands of people as well as scientists, triggered journalistic investigations, which were sometimes indeed grounded in documents. The reason is that in the past century, the military were indeed pursuing programs to design biological weapons, and while competing in the search for infectious agents, military microbiologists and virologists could not have ignored the bouquet of diseases carried by ixodid ticks.

Prison camp on Pechora River instead of a Nobel Prize

One of the best known tick-borne infections is tick-borne viral encephalitis. Regarding this disease, unsupported speculations exist, claiming that the pathogen was delivered onto the territory of the Soviet Union, specifically into the Soviet Far East, by the Japanese military.

Why blame Japan? First, this country is known to have summer (Japanese) encephalitis, an acute viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Second, in the early 1930s, when the Soviet Far East saw a massive outbreak of encephalitis, Japan was the only country that had not only been developing but also applying biological warfare.

The best known Japanese center for the development of bioweapons was the so-called Unit 731 under the command of Lieutenant General Shirō Ishii, chief medical officer. The unit was stationed in the occupied territory of China, 20 km south of Harbin; it worked with pathogens of various diseases, accumulated large quantities of pathogenic bacteria, infected insects with pathogens such as plague and cholera, and then tested them on prisoners and the local population. Unit 731 also developed porcelain bombs to be dropped from aircraft.

The epidemics caused by the actions of the Japanese military led, according to some reports, to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Chinese. Based on the documents captured during the liberation of this territory from Japanese troops in 1945, Unit 731 worked mainly with insects; however, Japanese prisoners of war also mentioned ticks; moreover, they mentioned that the military had been developing methods for using bioweapons not only in combat conditions but also for sabotage.

Therefore, it is no wonder that despite the lack of documents and direct witnesses to convincingly blame the spread of infected ticks in the Soviet forests on the Japanese military, these rumors were circulating vigorously for decades.

What does science say about that? The Japanese military might have indeed worked with ticks and the tick-borne encephalitis virus; however, this disease had long been known in the Far East, before the Japanese unit appeared. Both local residents and visitors suffered from tick-borne encephalitis, but this issue remained below the radar until the Soviet Union began the intensive development of the Far East in the early 1930s. When the USSR – Japan relations aggravated, military units were deployed in the forest regions of the Far East, and immigrants from the European part of the country and the military began contracting the disease en masse.

While imprisoned in one of the northern camps, Lev Zilber organized the production of yeast from reindeer lichen to serve as a source of vitamins for the treatment of severe vitamin deficiencies and dystrophies. In 1944, he patented, with the help of the NKVD, a new drug Antipellagrin.When the scientist presented his accomplishments at a conference of prison camp doctors, he was taken to Moscow, as hints were made about a possible retrial of his case. However, the request of the People’s Commissar of Health was rejected...

According to Zilber himself, “Two or three days later, they called me up and offered a position at a bacteriological laboratory. I refused. They made that offer again, twice. They persuaded and threatened me. I refused categorically. They kept me for two weeks with criminals... They called me up again. I again refused.” When the scientist refused to work with bacteriological weapons, he was assigned to a small obscure chemical facility, where he developed a new theory of cancer, which later gained worldwide fame

Now the time has come to open one of the many tragic and heroic pages in the history of Russia. In 1937, the USSR People’s Commissariat for Health sent to the area hit by the epidemic the Far Eastern Expedition, which was led by a well-known virologist Lev Zilber. The expedition team delivered to the site all the necessary laboratory equipment, mice for experiments and even monkeys.

By the way, the team leader himself not only had had experience in fighting epidemics but was once punished for that precisely because of conspiracy fabrications. When Zilber’s team successfully suppressed an outbreak of plague in Nagorno-Karabakh in 1930, he was arrested on charges of trying to infect with plague the population of Azerbaijan. Zilber spent several months in prison until renowned scientists and artists proved to the government the absurdity of those accusations.

Once again, he was assigned to a responsible mission – people were getting sick en masse for unclear reasons; suspicions were raised, attributing the cause to the mosquito-transmitted summer encephalitis. However, the scientists found out that the Far-Easterners were getting sick in spring, when there were no mosquitoes, and the symptoms were somewhat different. Working day and night, the scientists managed to identify, in record time, the pathogen vectors, i. e., ixodid ticks. Furthermore, they isolated several strains of the encephalitis virus and obtained antibodies to it.

The virologists gave the necessary recommendations on preventing infection, and the epidemic receded. It seemed like a victory of science, but someone was still willing to snoop, demand explanations, ask authorities to figure it out. Denunciations appeared about the possibility of infecting the population of Moscow with a new terrible virus through the city water supply system and about medical saboteurs back-pedaling the development of a cure for encephalitis, and they gave the blame precisely to those heroic doctors, the participants of the Far Eastern Expedition, calling them responsible for the planned (!) sabotage. Applications and letters came to the various authorities, and they were obliged to respond – in that memorable year of 1937, workers’ appeals led to real, tangible events. The expedition leader Lev Zilber was arrested, along with some of his coworkers, and sent to a prison camp.

Broken fates are not an unusual outcome of conspiracy theories…

Viral American Chernobyl

More than eighty years after the arrest of Zilber, the US Congressman Chris Smith claimed that in connection with sensational journalistic investigations, he studied some documents where he found evidence of intensive research to design bioweapons using infected ticks and various insects, which were carried out at some US government facilities, including the well-known center in Fort Detrick (Maryland) and the military ground on Plum Island (New York).

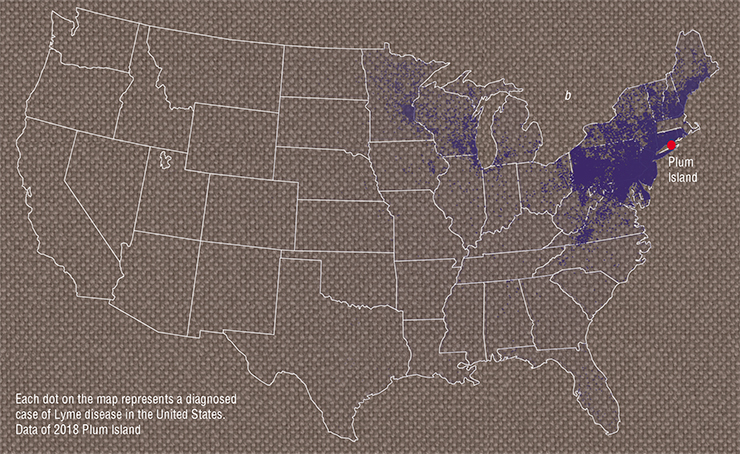

Smith was lobbying the interests of a Lyme (tick-borne borreliosis) patient advocacy group and initiated a heated debate around the involvement of the US military in the annual mass infection of American citizens. In the United States, official figures report about 30,000 cases of Lyme disease annually, whereas the actual figures may even be higher, since the majority of those infected do not seek medical help. About 10–20 % of the patients develop a chronic form of the disease, which, until recently, the official medicine in the United States did not recognize at all.

One expected Pentagon to give explanations: What kind of biological experiments were conducted? Who was the customer? Were there any cases when infected ticks accidentally or deliberately ended up outside the lab? The congressman demanded an investigation and an increase in funding for the development of means of combating tick-borne infections.

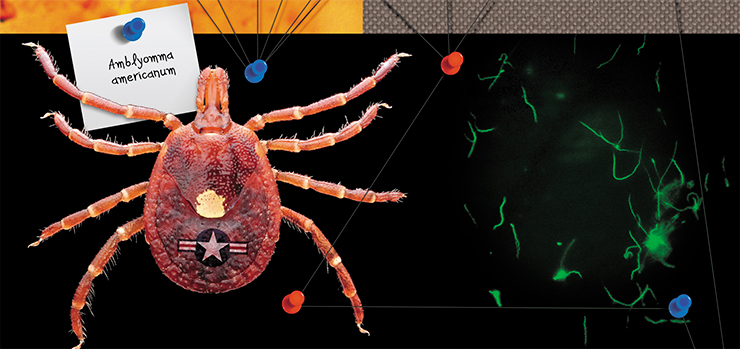

A direct trigger for this heated debate came from a book published in 2019 by a Stanford University professor Kris Newby, Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons. The author, who herself suffered from a chronic Lyme disease, told of the evidence she found – in the 1960s, the US military infected ticks with hard-to-detect pathogens. Newby claims that the military bioweapons experiments tested infectious agents carried by ixodid ticks, including Rickettsia bacteria, the causative agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Borrelia bacteria, the causative agent of Lyme disease.

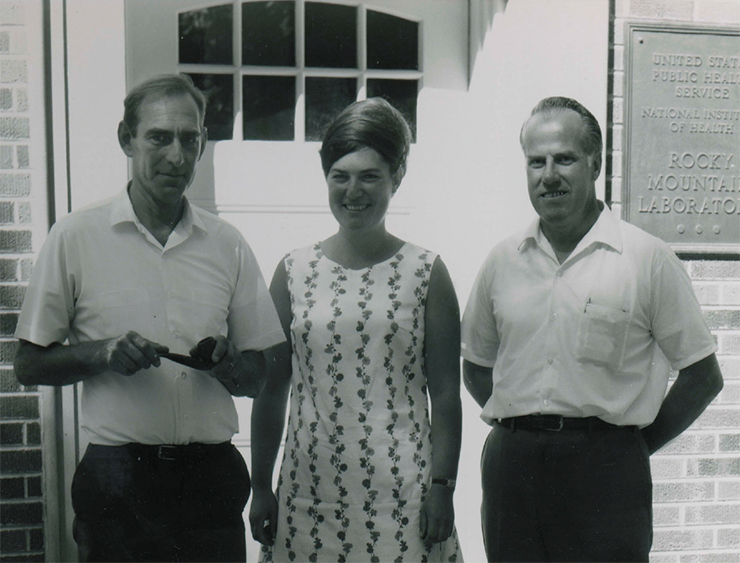

Newby acquired the core evidence for her book in 2013 from Willy Burgdorfer, a well-known biologist and a prominent figure in medical entomology, who used to work at a military laboratory on Plum Island and published an article in 1982 with the first description of the causative agent of Lyme disease.

Newby claims that Burgdorfer’s task was to breed fleas, mosquitoes, and ticks and infect them with dangerous viruses and bacteria that cause human diseases. The military planned to deliver infected insects and ticks to enemy territory using aircraft. In order to find out how quickly the infection carriers can spread, they released ticks in some areas of the United States and tracked their migrations.

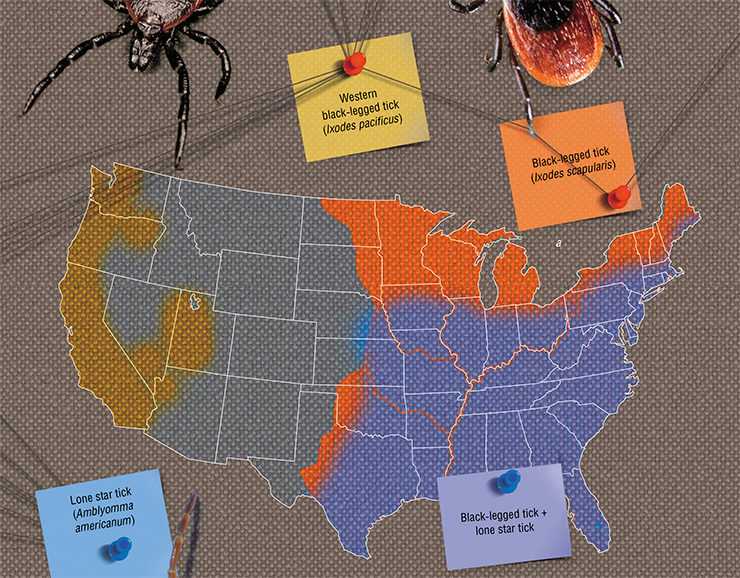

In connection with these claims, journalists drew attention to the fact that in the 1980s, lone star ticks appeared in the neighborhoods of Plum Island, a tick species that was part of the laboratory experiments. Previously, these ticks occurred only in the south of the country, in Texas, but today they live in large quantities in the east too: in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

After talking to Burgdorfer, Newby concluded that the first massive outbreak of Lyme disease in the late 1960–70s occurred after the release of Borrelia-infected ticks into the environment. In her book, she writes about Burgdorfer mentioning an accidental release of infected ticks outside the lab. By the way, patients were often reported to have three infectious at once: Borrelia, Rickettsia, and Babesia.

Interpreting the scientist’s statements, Newby speaks of the causative agent of Lyme disease in the United States not as a common, widespread local pathogen but as a very dangerous strain that was specifically selected in the lab to maximize the damage to people, and she calls the virus leak “an American Chernobyl.”

However, the journalist could not find any official documents to support Burgdorfer’s claims about the tick leaks on Long Island. Although Newby put forth a hypothesis about biowarfare tests, she failed to connect the dots to substantiate her conclusions. Meanwhile, the journalist believes, too, that Burgdorfer did not tell the whole truth, as he himself admitted at the end of the interview. Since the scientist died in 2014, we might only learn more if documents are published, which are, however, still classified.

Cold war weapons

Newby argues that if Burgdorfer had not made his confession, the secrets of Lyme disease and the military bioweapons program would have died with him. However, other evidence also exists about secret experiments of that time.

Thus, an entomologist James H. Oliver from the University of Georgia, who worked in the 1950s at Fort Detrick, told reporters about his assignment under a top secret program to develop methods for mass cultivation of ticks and mosquitoes and find ways to most effectively deliver them to enemies and options for spreading infectious agents. He said, “I’m still leery talking about it, because I think they might put me in jail because I’m delivering secrets. It was a crazy time.” Another entomologist, Jeffrey Lockwood, author of the famous book Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War, published in 2008, told about studies during the Cold War aimed at investigating the ability of ticks to spread pathogens that cause tularemia and viral diseases.

Let us come back to Lyme disease. Back in 2004, Michael C. Carroll, author of the bestselling book Lab 257: The Disturbing Story of the Government’s Secret Germ Laboratory, told about an outbreak of a rare disease in July 1975 in the town of Old Lyme, not far from Plum Island. According to the author, a bioweapons laboratory with German specialists existed there after World War II. The biological warfare developed at that lab included infected insects, which were planned to be dropped from aircraft.

The journalist also mentioned documents related to tick experiments of the 1950s, during the Korean War, when there were open talks about the possibility of using biological agents for military purposes. The Plum Island laboratory conducted experiments involving field trials, i. e., the release of infectious agents into the environment using deer and birds as carriers. However, the experimental animals could have come in contact with wild ones because the laboratory premises were not isolated well enough. Although it was believed that infected individuals would have remained within the limited area of the island, Carroll argued that birds and even deer (by swimming), and hence the infected ticks, could have reached the mainland.

In her book, published a decade later, Newby came to the same conclusion as Carroll – the most likely source of infected ticks was the Plum Island laboratory. The pieces of evidence published by these two authors complement, rather than contradict, each other.

Clearly, all these books, like other publications on this topic, represent creative endeavors undertaken by journalists seeking to present their stories as sensationally as possible. To this end, they might have quoted documents not entirely correctly, or even made something up to support their versions. However, they all had had ample opportunity to operate with completely reliable facts and documents, as unambiguously evidenced by the 1964 book Tomorrow’s Weapons: Chemical and Biological by a professional military man, US Brig. General J. H. Rothschild. In this serious work, Rothschild described in detail the possible options for the military use of infectious agents and examined their advantages, disadvantages, and features of application. Among those pathogens, he mentioned tick-borne infections.

Pros and cons

The interest in Newby’s book is fueled by the topicality of the tick-borne infections issue and the plausibility of the author’s apparently fiction-like assumptions. However, the Cold War documents, too, demonstrate that the plans of the military were indeed fiction-like and sometimes even absurd.

What today sounds incredible may well have been a fact of life back then, when the DDT chemical insecticide (subsequently discovered to be a carcinogen, mutagen, embryotoxin, neurotoxin, immunotoxin, etc.) was widely used in agriculture and even as a therapeutic drug (an inducer of liver enzymes) for the treatment of children and for the treatment of Trichomonas colpitis in women. At that time, drug trials were almost nonexistent, with new drugs being tested on unsuspecting patients. At that time, pregnant women were prescribed a sedative drug Thalidomide, which turned out later to be genotoxic, causing about 10,000 children to be born with congenital deformities.

In 1969, US President Richard Nixon banned the development of offensive biological weapons and ordered the destruction of the stockpiles in arsenals. This happened after scientists, at the initiative of the outstanding US geneticist and biochemist Joshua Lederberg, called for a ban on the development of mass destruction weapons threatening the mankind. In 1972, an international convention was signed on the prohibition of the development, production, and stockpiling of bacteriological (biological) and toxin weapons and on their destruction.

However, by that time, developed countries had created biological warfare designed to defeat enemy personnel (yellow fever virus, anthrax bacteria) and kill farm animals (African swine fever, rinderpest) and plants. Facilities had been set up for the production of these pathogens as well as means for aircraft delivery and distribution using bombs and aerosol sprays.

American bioweapons developers conducted experiments in the New York subway. They placed model bacteria in the ventilation systems, and air currents from moving trains carried them through underground tunnels. Experiments showed that pathogens could get in the lungs of millions of passengers in literally a matter of days. Tasked by military officials, researchers at Ohio State University conducted experiments on infecting monkeys via aerosol with Rickettsia bacteria, which cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Most of the 68 infected animals died within 10 days. Data of many other such experiments remain classified.

The Soviet Union, too, had powerful organizations for R&D and stockpiling of biological weapons. They conducted experiments in uninhabited areas, such as a deserted island in the Aral Sea. It became known that an accidental release of anthrax spores into the atmosphere occurred at a manufacturing facility in the Urals, leading to the death of several dozen residents of the nearby city.

In such a context, the hypothesis about the spread of Lyme disease from a classified military facility no longer seems like fiction. By the way, it is amazingly consistent with the geography of the current spread of tick-borne borreliosis in the United States, with its center in the neighborhoods of the notorious Plum Island. But let us now give the word to the opponents of the military hypothesis.

One of the counterarguments states that the causative agent of Lyme disease was discovered by Burgdorfer only in 1982. That year, however, the scientist published the results of his research in open press, so there is reason to believe that he began working on that topic much earlier, three decades before that publication. For example, back in 1952, Burgdorfer published an article on the technology of tick infestation in laboratory conditions. In 2013, when he was asked a direct question whether Borrelia organisms had indeed been that (or related) pathogen with which he had injected ticks, Burgdorfer answered in the affirmative in front of the camera.

Today, Pentagon officials predictably refuse to comment on this situation. Those military experts that give interviews argue that ticks and Borrelia bacteria are not the best agents for developing bioweapons. Ticks do not fly but rather move slowly, and humans can easily spot them. By themselves, ticks cannot spread in urban settings, and Lyme disease develops slowly without causing immediate serious damage to health.

However, these objections do not appear particularly convincing. Lyme disease can cause great damage to national economy – today, about 1.3 billion dollars are spent annually in the United States to cover the direct medical costs of treating patients with Lyme disease. The argument that Borrelia-carrying ticks are not a rational choice for bioweapons developers does not stand to scrutiny either since many military programs were not only irrational but simply insane. Suffice it to recall the thought-broadcasting projects for communicating with submarines or the studies of “torsion fields.”

Sequencing of Ötzi’s genome revealed nearly two-thirds of the genome of the bacterium known today as Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of tick-borne borreliosis, or Lyme disease. Ötzi’s surviving tissues showed no clear signs of the disease, but a clinical examination detected signs of arthritis, which is typical of the chronic form of Lyme disease. Moreover, the tattoos on Iceman’s spine and ankles and on the back side of his right knee might have been an attempt to alleviate joint pain, typical of this disease

Scientists hold more serious arguments in stock. According to some studies, Borrelia bacteria appeared on the American continent a long time ago. They are found in mouse and human tissues that have been kept in museum collections since the 1890s and in ticks collected on Long Island back in the 1940s.

Moreover, researchers from Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) built up in 1984–2013 a collection of Borrelia organisms from the United States and Southern Canada and decoded 146 bacterial genomes, revealing an enormous genetic variability (Walter et al., 2017). A historical and geographic reconstruction of the origins of this diversity showed that Borrelia bacteria existed in North America at least about 60,000 years ago and occurred in the northeast of the country and in the Midwest.

Researchers associate the likely causes of the recent Lyme disease epidemic with environmental changes that began as early as 700 years ago, after the colonization of North America. Deforestation and intensive hunting; a sharp surge in the population of white-tailed deer, one of the major tick hosts; all that coupled with the climatic changes of the last century greatly expanded the potential habitats of the pathogen vectors, i. e., ixodid ticks. Moreover, in all the regions surveyed, researchers found even more pathogenic strains B. Burgdorferi, which are associated with a severe course of the disease, and they believe that those strains had formed independently against a different genomic background. The process that we are witnessing today is the continued spread of the various Borrelia strains not only from the northeast but also in other directions.

Given the knowledge and technology of the mid‑20th century, Burgdorfer could not possibly have created, or genetically modified, Borreliae, as journalists suggest. Nevertheless, he was actually able to select the most pathogenic strains. However, the chances that the current dire Lyme disease situation in the United States traces back to a pathogen leak that happened more than half a century ago are virtually nil.

Considering the scientific arguments, we have to admit that Lyme disease is a typical natural focal infection for the United States. Meanwhile, we should be cautious about Burgdorfer’s confessions, the main source of evidence in support of the military theory. In 2013, this researcher was 88 years old; moreover, he was seriously ill (by the end of life, he suffered from diabetes mellitus and Parkinson’s disease). In addition, Burgdorfer’s colleagues noted his penchant for black humor and admitted that he could have pranked TV people, just for fun.

Considering the scientific arguments, we have to admit that Lyme disease is a typical natural focal infection for the United States. Meanwhile, we should be cautious about Burgdorfer’s confessions, the main source of evidence in support of the military theory. In 2013, this researcher was 88 years old; moreover, he was seriously ill (by the end of life, he suffered from diabetes mellitus and Parkinson’s disease). In addition, Burgdorfer’s colleagues noted his penchant for black humor and admitted that he could have pranked TV people, just for fun.

By the way, Newby, who published the exposé, also mentioned that most of her assumptions could be wrong although she was more than sure that the US military conducted thousands of experiments on creating bioweapons, including using ticks as infection carriers, and that on some occasions, those lab ticks got into nature. In her opinion, the government should declassify the details of all those field experiments to help develop modern methods for combatting pathogens.

Obviously, the Cold War history still has many gaps to fill and dots to connect, and declassified documents might one day reveal many surprises. In the meantime, they provide most ample opportunities for bestselling authors who seek to attract readers by intimidating them with fear of disease and entangling them in an avalanche of bogus stories.

References

Akiyama H. Osobyi otryad 731 (Special Unit 731). Moscow: Inostrannaya Literatura, 1958 [in Russian].

Akiyama H. Tokushu Butai Nanasanichi. Tokyo: San'ichi shobo, 1956 [in Japanese].

Lockwood J. A. Six-legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. USA: Oxford University Press, 2008. P. 9–26.

Newby K. Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons. Harper Wave. 2019. 336 p.

Rothschild J. H. Tomorrow's Weapons: Chemical and Biological. McGraw Hill, 1964.

Vlasov V. V., Tikunova N. V. Chronic Lyme disease: nonexistent illness or wrong diagnosis? // SCIENCE First Hand. 2019. V. 53. N 3. P. 32–41.