The Denisovan comes back

There was nothing special about this fragment of a fossil bone. Found in loose cave deposits alongside a multitude of animal bones, stone chips and artifacts, it was described, marked and packed as appropriate. Even after its “human” nature was established, it did not make the news although for the Denisova Cave anthropological material was a rarity. If this bone fragment had been found ten years earlier, it would have gone to a store-room of a research institute museum or become a modest exhibit marked “Homo sapiens.” It was with this label that the future “star” arrived at Prof. S. Pääbo’s laboratory. “In spring 2009 we received a bone fragment from Anatoly Derevyanko… The bone was tiny, and I didn’t pay much attention to it thinking that when we have time, we’ll analyze it for the presence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Possibly, if the bone appears to be Neanderthal, we’ll be able to measure the degree of this DNA variability in the easternmost Neanderthals…” Today, this find is world famous – the primitive Denisovan girl has turned upside down our self-image just with her little finger

“Time will bring to light whatever is hidden.”

Quintus Horatius Flaccus

There is hardly a single person who has never wondered how the first sensible human being appeared on our planet. By the way, according to recent surveys, almost half of the USA citizens and a fair share of Europeans cast a vote for the divine origin. Some of the respondents believe in extraterrestrial intervention.

However, the large community of scientists engaged in human origin and evolution was not unanimous in the interpretation of the enormous factual material accumulated since the late 19th century, when Pithecantropus erectus, the first candidate for the title of our ancestor, was discovered. The archaeological discoveries made in South Africa during the following century and results of the first genetic analysis of modern human populations proved just one thing: the ancestral home of all the mankind was Africa.

There is approximately three million years between modern humans and the most ancient Homo representatives; during that time humans not only acquired their present look but also settled all around the globe. Fossil anthropological remains and archaic tools of the oldest stone industries suggest three waves of the “Migration Period” from Africa to Eurasia. Scientists, however, are divided on the issue of what happened afterwards.

The monocentric theory shared by most scholars implies the explicit priority of Homo sapiens over his contemporary hominines, ultimately displaced by the superior species. Yet, this hypothesis fails to explain, among other things, why the Upper Paleolithic culture traditionally attributed to modern man sprang up virtually simultaneously in the regions of Eurasia very far apart. Another vital question is the principal differences of the stone industries of the early Upper Paleolithic implying at least the cultural continuity of the primitive population of each region.

Academician A. P. Derevyanko, upon the analysis of an immense body of archaeological data including the research results of the Paleolithic objects discovered during the expeditions organized by the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS in Central, North and East Asia, became a strong advocate of the multiregional concept of human origin. The most compelling arguments in its favor, however, relied on the extensive studies conducted for many years in Russian Altai, started at the time by an outstanding Soviet archaeologist and historian, Academician A. P. Okladnikov.

An interdisciplinary research into the Altaian Paleolithic has shown that the evolution of cultural traditions lasted there for at least 300,000 years (including the establishment of the Upper Paleolithic 50,000—40,000 years ago) without any noticeable signs of outside influences. And yet, what were they like, those people who made artifacts and decorations typical of the early Upper Paleolithic before Europeans did it?

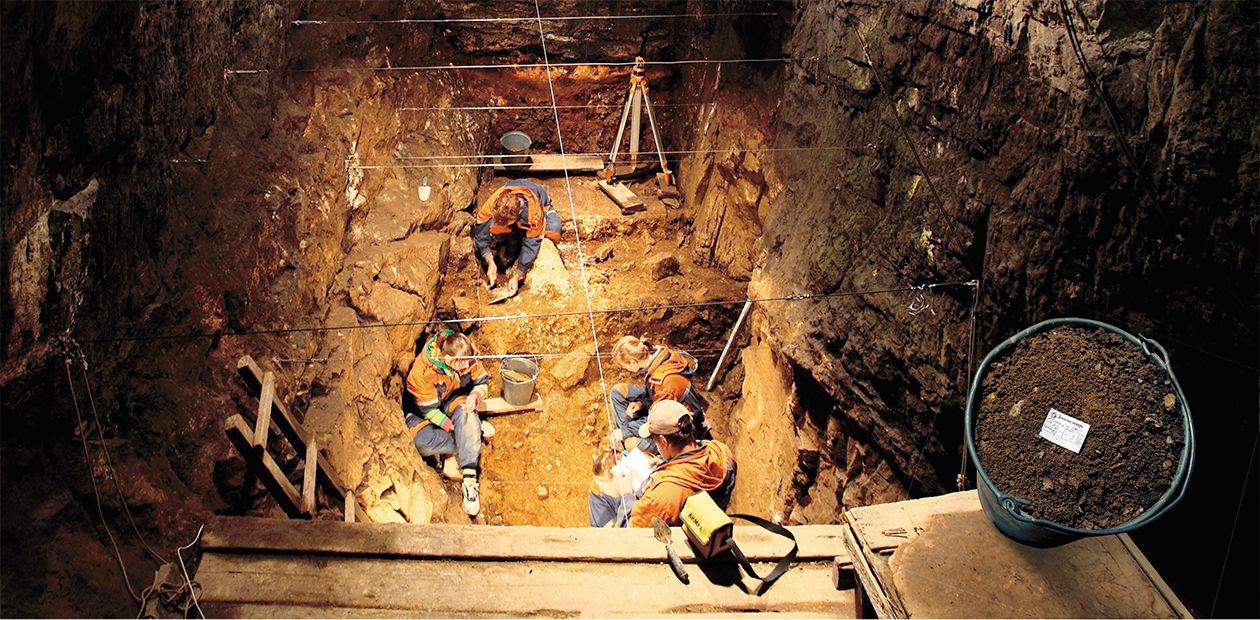

Regrettably, the Altaian Paleolithic was stingy with anthropological evidence, which, in addition, consisted of the rare findings of teeth and bone fragments not allowing restoration of the appearance of their owners. In 2005, A. P. Derevyanko wrote, “Our most optimistic expectations are to find in Altai a skeleton of the Paleolithic man. We have a couple of Paleolithic findings currently studied at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig: some teeth and a bone fragment. But a complete skeleton is an archaeologist’s fondest, albeit specific, dream.” No complete skeleton of a fossil man has been discovered on Altai so far, and yet the reality has exceeded our grandest expectations. Owing to the multidisciplinary approach and international cooperation Siberian archaeology today is at the forefront of global science.

Firstly, the results of the decoding of the mitochondrial DNA extracted from the bone remains discovered in the Okladnikov and Denisova caves, conducted by S. Pääbo and his colleagues, became part of the evidence that “rehabilitated” Neanderthals, previously crossed out of the humankind’s family tree. The most sensational result, though, was produced by the paleogenetic analysis of the little finger bone and a few teeth found in the Paleolithic deposits of the Denisova Cave. The analysis of both mitochondrial and nuclear genome has shown that the inhabitants of the cave, the so-called Denisovans, substantially differed both from the Neanderthals and modern humans.

The immense archaeological and anthropological material collected as well as the data of paleogenetic research suggest the existence of several large geographic zones based in Africa, East and South-East Asia, and in Europe, together with North and Central Asia, where the early forms of Homo sapiens – African, Oriental, Neanderthal, and Altaian – formed independently. All of them have contributed, albeit unevenly, in the formation of modern man.

Prof. Mikhail V. Shunkov,

Director of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography

of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences