The Pleasure of Discovery, or a Hunt for Hominins

The material is based on the articles by Prof. Anatoliy P. Derevyanko

and Prof. Mikhail V. Shunkov, published in different years in SCIENCE First Hand

When Alexey Pavlovich Okladnikov was asked what he valued most in life, he replied it was the pleasure of a new discovery. Recently I was asked a similar question, and I understood that no archaeologist can formulate the gist of our profession better. Certainly, big ideas do not spring out of nowhere, researchers come to them step by step. Any discovery requires numerous validations, which is the usual practice. When we go on expeditions, we do not seek for something absolutely unknown; normally, expeditions are preceded by thorough preparations, especially if the region is new for digging. We study geology, geomorphology, and natural conditions that existed there twenty thousand, two hundred thousand, or a million years ago… Today, discoveries rarely come as a surprise. What you don’t expect is the quality of the discovery and a chain of related discoveries stemming from it.

Academician Anatoliy P. Derevyanko

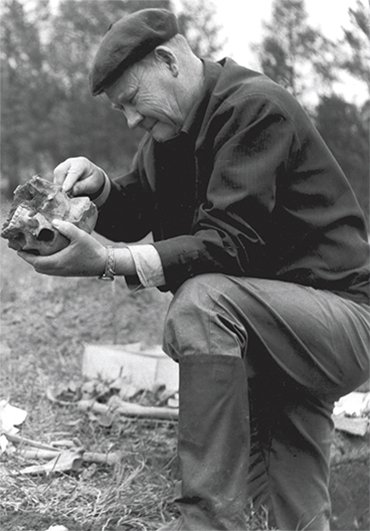

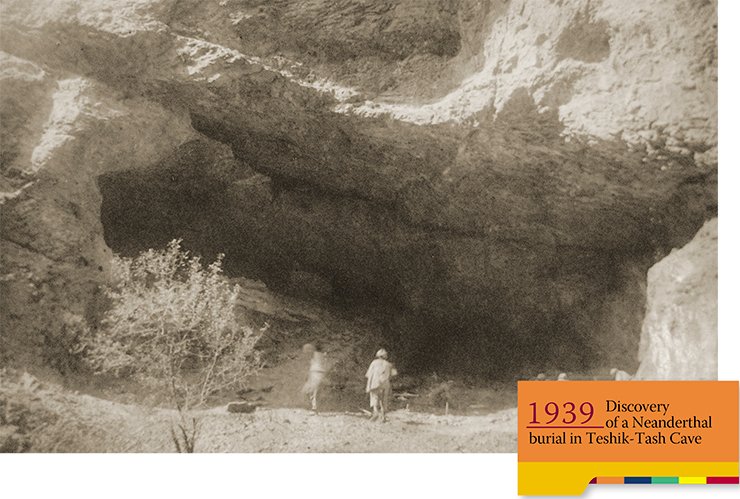

In the late 1930, an outstanding archaeologist, historian, and explorer Alexey Okladnikov made one of his sensational discoveries when he found the remains of a Neanderthal child in Teshik-Tash Cave (Uzbekistan). In spring 2017, a group of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, headed by Prof. Svante Pääbo, announced that they developed a method to retrieve hominin DNA from sediment samples collected in once-inhabited caves. What do these two events, separated by decades and thousands of miles, have in common?

The history of science knows no more alluring and controversial question, a question that would attract universal attention, than the origin of life and the evolution of man. The non-Biblical version of human origin is rooted in the hazy 1600s, when the works of the Italian philosopher Lucilio Vanini and the English lord, barrister and theologian Mathew Hale, with the speaking titles On the Primitive Origin of Man (1615) and The Primitive Origin of Mankind, Considered and Examined According to the Light of Nature (1671), were published. In summary, by the late 19th century, the idea of man as a product of a long evolution of more primitive anthropoid beings had germinated and ripened. Just one small thing was lacking – to discover this pithecantropos (from Greek pithekos “ape” and anthropos “man”) “in flesh,” which was done in the early 1890s by the Dutch anthropologist Eugene Dubois, who found the remains of a primitive hominin on the island of Java.

Since that time, another issue, as topical and controversial as man’s descent from apelike ancestors, was placed on the agenda: geographical centers and development of anthropogenesis. Thanks to the amazing discoveries made in the recent decades by the cooperative efforts of archaeologists, anthropologists, and specialists in paleogenetics.

Until recently, it was only possible to determine DNA sequences and whole genome sequences from present-day individuals from which DNA can be isolated in good condition from fresh tissues such as blood. To evolutionary scientists this is somewhat frustrating because it represents an indirect way to study the past: one studies DNA sequences that exist today, uses the best models we have for how mutations accumulate and estimates what common ancestors may have looked like. This is frustrating because what we have are estimates subject to many uncertainties for example as a result of the mutational models used. However, by the end of the last century the breakneck development of molecular biology had given us methods for retrieving DNA sequences from archaeological and paleontological remains first of Late Pleistocene animals and then humans (Pääbo, 2014).

…All around us is the opulence the south. Even here, in this somber gorge, this land strikes with its lavishness. Opulence blooms everywhere: in colors, in aromas, in contrasts. Grapes ripen at the foot of the mountains; the never-melting snow blinds us with its dazzling glare from mountain tops.

The cave is dusky though it isn’t deep. It descends 20 meters inside the mountain, and its ceiling is 7 to 8 meters high. It seems that enough light should be reaching its interiors. But the mountains… They obstruct the sun. Its rays seldom touch the cave floor. At first glance, it seems strange: Why would the primitive man avoid the sun? But in a moment, the sun rises in the east and ascends higher and higher up the sky. Finally, sunrays reach inside the cave, bringing life into it. Yes, the whole place revives from a huge mass of wasps and bees. Oh! The primitive man had thought about that when choosing a place to live.

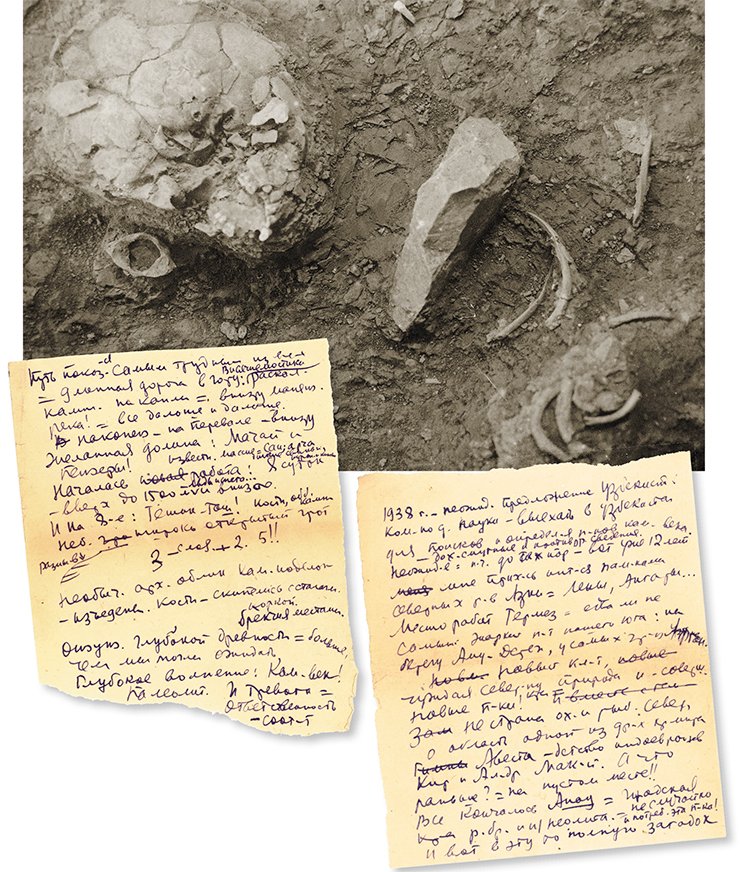

<…> The cranium was lying with the crown down. It must have been crushed by a falling clot of earth. The skull was small! A boy’s or a girl’s.

With a spade and a brush, Okladnikov began widening the dig. The spade hit against something hard. A bone. Another one, and one more…It was a small skeleton, the skeleton of a child. An animal must have found its way into the cave and picked the bones. They were scattered, some of them gnawed and bitten.

With a spade and a brush, Okladnikov began widening the dig. The spade hit against something hard. A bone. Another one, and one more…It was a small skeleton, the skeleton of a child. An animal must have found its way into the cave and picked the bones. They were scattered, some of them gnawed and bitten.

But when did this child live? In what years, centuries, millennia? If he was a young master of the cave when people who worked stone lived here … The thought was terrifying. If it was so, the child was Neanderthal. A man who lived tens of thousands or even a hundred thousand years ago. He must have a very pronounced brow ridge and no chin.

The easiest thing to do was to turn the cranium to have a better look but this would have disrupted the excavation plan. They had to complete the excavations around it leaving the child’s bones untouched. The dig around them will deepen, and the bones will remain as though lying on a pedestal.

The archaeologist couldn’t sleep that night. He thought about what may come out of that find and sneaked amazed glances at the workers who didn’t sleep either. They sat around a fire, arguing… In the morning, Ikram said:

“They are leaving. Don’t want to work here. They say: Muslims must not dig out the dead.”

What will he do without the workers? If they go back to the kishlak [village], no one will ever come here.

<…> The kolkhozniks sat down in a circle, their deep, angry eyes piercing at Okladnikov.

He thought: What should he begin with? Should he tell them about the years of searching, about his struggle and determination, stunning to everyone in a man of his age? Tell them about his faith, fanatical faith, which, however, required proof? How he searched for this proof in taiga along the Lena River, near the desolate shores of the Angara, be it rain or heat? How they camped in tents, from the breaking of ice in spring to snowflakes in autumn, sleeping on frozen earth, about ice-cold rivers out of which you come stiff frozen, about clouds of mosquitoes, whose bites made your face burn, and you could barely speak, your eyes and lips swollen, but you couldn’t hide from them. Against all odds – they marched further into the taiga, in search for answers, because they believed in the truth of history. In the truth without which people cannot live in this world yet which remains hidden in the millennia.

He looked at the workers around him. Grim faces, mistrustful eyes… They don’t speak Russian. No, he must be brief. He must talk only about things that are familiar to them, things they’ll understand.

Okladnikov shook his head, as he usually did when he took up on a hard business, and his stubborn curly hair pressed against his forehead.

“Long, very long ago lived a man. He was called a Neanderthal. We all come from this man. All people, no matter if their skin is white, or red, or black – all of us are equal, like brothers.”

Okladnikov spoke slowly, so that Ikram could translate him. He saw the eyes of the Uzbeks grow warmer; they whispered to one another, shaking their heads approvingly. They were his friends, and he regretted he hadn’t told them from the very beginning about himself, about Siberian peoples, about the amazing life of archaic humans, whose traces he had found in taiga. Those men became even closer to him: their fate had so much in common with that of Northern peoples.

“Now ask them: Do they agree to continue the excavations?”

<…> The kolkhozniks didn’t sleep all night. They sat around the fire, drank green tea, sipping loudly, and argued.

In the morning, one of them, a tall, long-bearded man, packed his sack and walked down the hill, not looking back. The workers stared sullenly after him. Ikram dropped a word at him; everyone broke in laughter.

“I told them,” he explained to Vera Dmitrievna, “that wasting words on a fool is like nailing a stone. They liked my words very much. They’ve changed completely after your husband’s lecture.”

Then he drawled pensively, looking at Okladnikov.

“In the hands of a true blacksmith, iron flows like water.”

The child’s bones were left untouched. They were even covered. The archaeologists dug around them, and the bones were on a ground pedestal, which became higher every day. It appeared to be growing from the underground.

The night before that memorable day Okladnikov had trouble falling asleep. He was lying on his back, hands behind his head, looking up at the black southern sky. Far above, the stars were swarming. They were so many that it seemed there was not enough room for all of them. That faraway world inspired awe and at the same time instilled serenity. You felt like thinking of life, eternity, the faraway past and the faraway future.

What could the ancient man be thinking about when he was looking up at the sky? It was the same as it is now. Maybe, sometimes he also had trouble falling asleep, was lying in the cave and looking up at the sky. Did he only have memories or did he have dreams as well? What was that man? The stones told a story but there were many things about which they remained quiet.

Life buries its traces deep underground. Overlaying them are new traces, which with time also go down. And so it happens century after century, millennium after millennium. Life puts layers of its past in the ground. Paging through them, an archaeologist can learn about the doings of the people who used to live here and to determine, virtually without mistake, the times when they lived.

Drawing the curtain above the past, they removed land layer by layer, as time had put them.”

Before starting the excavations, Okladnikov, as usual, dug out a test pit.

The pit revealed five cultural layers, i. e., five layers of earth retaining traces of man who lived there. The layers alternated with sterile ones, which deposited during the periods when man did not inhabit the cave.

Man came to this cave five times and left it five times. What made them leave? Giant catastrophes? The sterile layers contain silt and sand. There are boulders in the cave. Is this evidence of floods? Or, perhaps, man left the cave in search for better hunting grounds? Or a formidable enemy attacked people and forced them out of the cave? And then, again and again, man returned to these amazingly scenic places.

by Ye. I. Derevyanko and A. B. Zakstelsky

The first representative of archaic people that became known to science is the Neanderthal, Homo neanderthalensis. The Neanderthals mostly lived in Europe but traces of their presence have also been discovered in Near East, West and Central Asia and in the south of Siberia. These short stumpy people, physically strong and well adapted to the severe conditions of the northern latitudes, in terms of the brain volume were on a par with modern humans. In a century and a half that has passed since the first Neanderthals’ remains were discovered, hundreds of their sites, settlements and burial grounds have been studied. It has turned out that these archaic people not only made quite advanced tools. According to Okladnikov, the excavations in Teshik-Tash Cave (Uzbekistan) “revealed an unpredicted, truly amazing picture, a picture no researcher had ever seen: the skull of a Mousterian man was circled, once in a strict order, clearly in accordance with a premeditated plan, with ibex horns. That arrangement provided compelling evidence of a rational mind, a logical plan of action, an entire world of ideas that stood behind that action.”

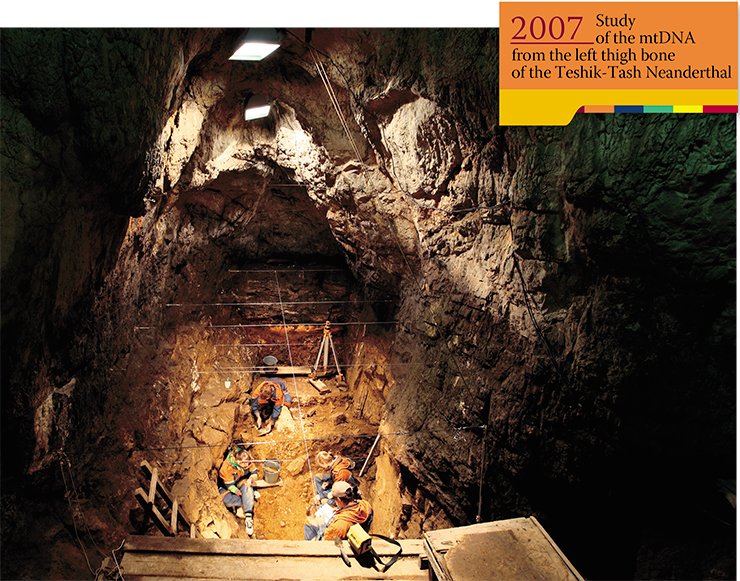

No wonder that prior to the beginning of the 21st century, many anthropologists classified the Neanderthals as an ancestral form of modern humans; however, after mitochondrial DNA from their remains was examined, they were treated as a dead end. In 2007, Pääbo’s laboratory investigated the mtDNA from the left femur of the Teshik-Tash Neanderthal child and from the bones found in Okladnikov Cave. Their comparison with earlier decoded genomes showed similarity between the Siberian and European Neanderthals.

by A. P. Derevyanko (1980)

The Neanderthals were considered to have been forced out and replaced by modern humans of African descent. Further studies have shown, however, that the relations between the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were not as simple as that. Currently, there is no doubt that on the border of the areas populated by these humans not only cultural diffusion but also hybridization and assimilation took place. Today, the Neanderthals are classified as a sister group of modern humans, and their status of “man’s ancestors” has been restored.

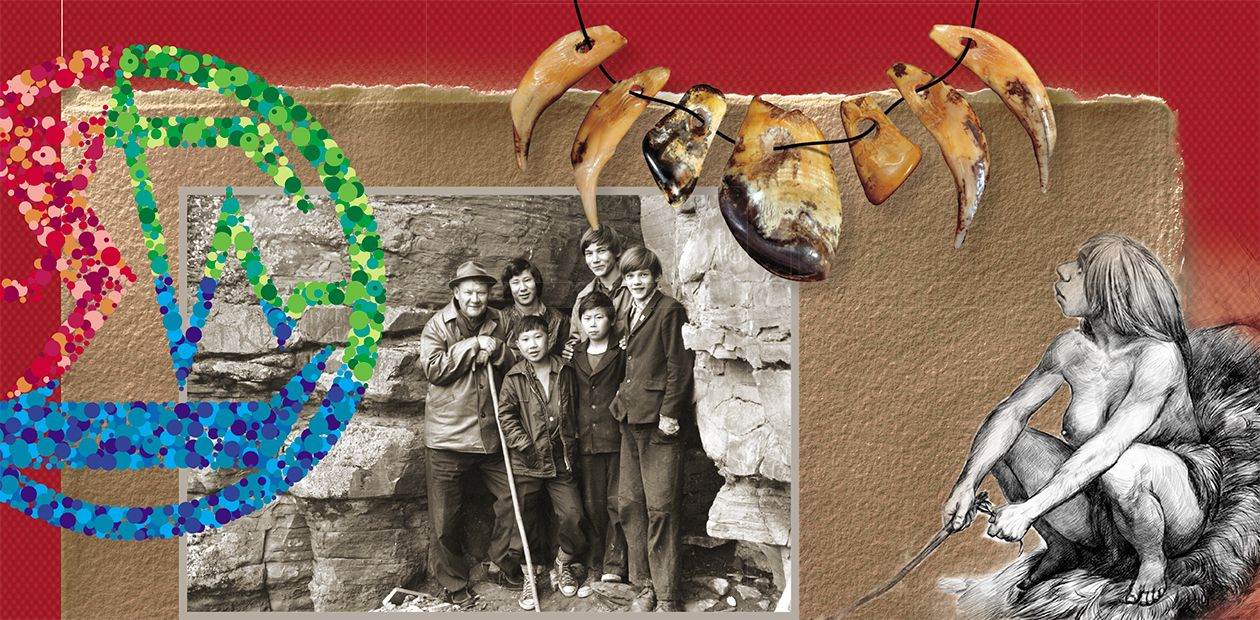

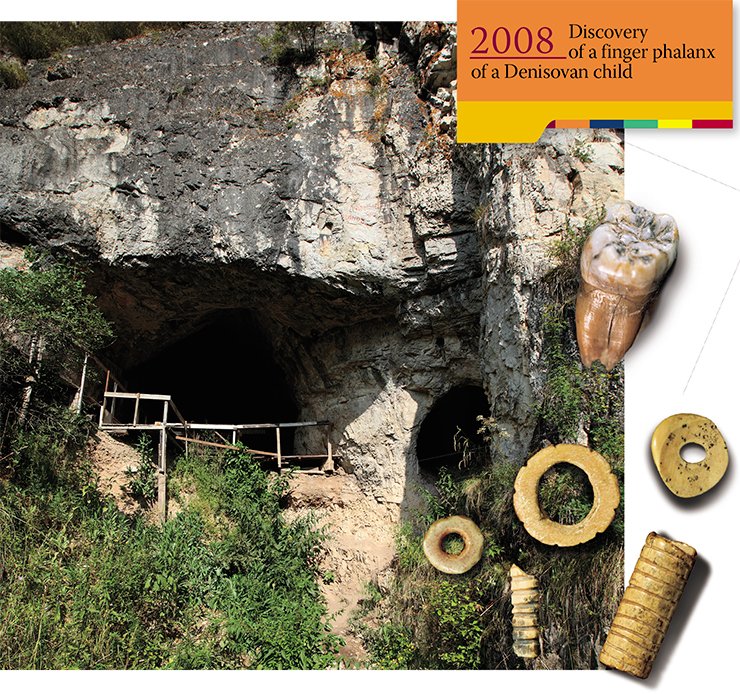

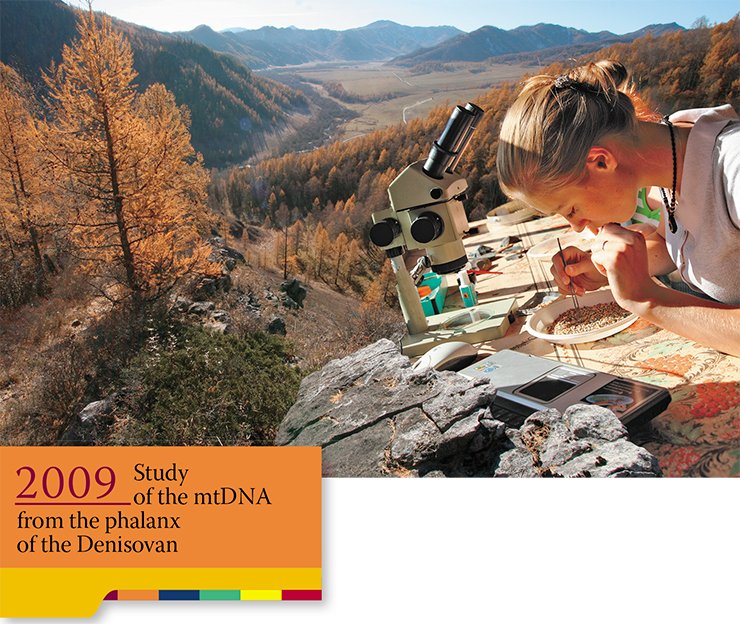

In the rest of Eurasia, the development of the Upper Paleolithic followed a different path. Let us trace this development through the example of the Altai region, which has produced some astonishing results obtained with the help of the paleogenetic examination of the anthropological findings from Denisova and Okladnikov caves. Paleogenetic studies confirmed that the remains discovered in Okladnikov Cave were Neanderthal whereas the results of the sequencing of mitochondrial and then nuclear DNA from the bone samples discovered in the occupation layer of the Upper Paleolithic early stage in Denisova Cave sprang a surprise on the researchers.

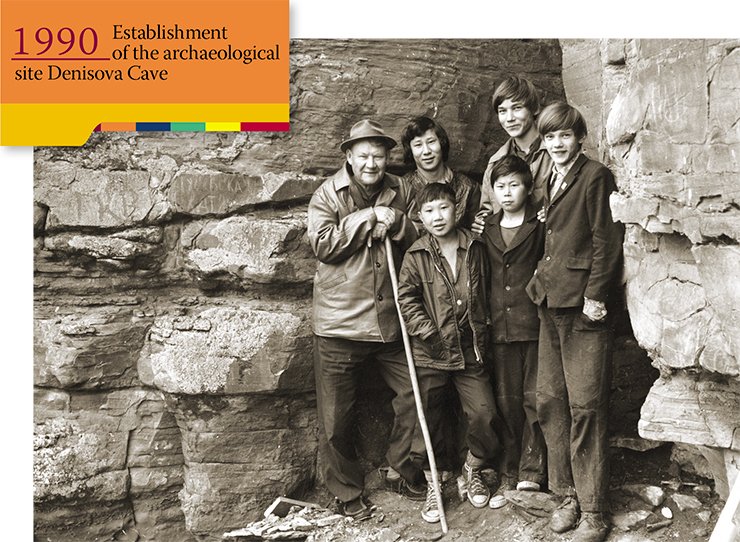

Okladnikov was succeeded at the director’s post in 1983 by his student, a renowned expert in ancient history Anatoliy Derevyanko, who initiated a reorganization of humanities at Novosibirsk Science Center. Interdisciplinary studies of Asian antiquities in close cooperation with leading science centers of Russia, Europe, Asia, America, and Australia brought fundamental results, rated among the most outstanding achievements of modern archaeology.

The bone fragments proved to belong to a new fossil hominin, unknown to science, who was given the name of Homo sapiens altaiensis, or Denisovan, after the locality where he was discovered.

The genome of the Denisovans differs from the reference genome of a modern African by 11.7 %, and that of the Neanderthal from Vindija Cave, Croatia, by 12.2 %. This similarity testifies that the Neanderthals and Denisovans are sister groups with the same ancestor, who branched off the man’s mainstream evolutionary trunk. These two groups separated approximately 640,000 years ago, taking the path of independent development.

The genome of the Denisovans differs from the reference genome of a modern African by 11.7 %, and that of the Neanderthal from Vindija Cave, Croatia, by 12.2 %. This similarity testifies that the Neanderthals and Denisovans are sister groups with the same ancestor, who branched off the man’s mainstream evolutionary trunk. These two groups separated approximately 640,000 years ago, taking the path of independent development.

Judging by the archaeological data, 50,000—40,000 years ago, in the northwestern region of Altai two different groups of primitive people lived next to each other: the Denisovans and the easternmost population of the Neanderthals, who came there at about the same time, probably from the territory of modern Uzbekistan. The roots of the culture whose carriers were the Denisovans can be traced back to the earliest sequences of Denisova Cave, as it was mentioned earlier. Interestingly, according to the panoply of archaeological findings reflecting the development of the Upper Paleolithic culture, the Denisovans were not only on a par with the anatomically modern humans inhabiting at that time other territories but in some respects were superior to them.

The neighborhoods of Russia’s largest archaeological stationary site Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains house the most ancient settlement of primitive man in North and Central Asia—the Karama site, a remnant of the first migration wave from the African “cradle.” Denisova Cave itself achieved worldwide fame after the recent discovery of a new, previously unknown representative of archaic mankindThe discovery of the Denisovan, a new member of the hominin family, is of critical importance for modern science. For a long time, Siberian archaeologists believed that the population that inhabited South Siberia and created the earliest blade industry in Europe had been humans of a modern physical type. However, when the evidence for an unknown subspecies became compelling, scientists realized that the development of modern man followed a much more labyrinthine path than they previously thought. The hypothesis of a linear evolution of mankind, which prevailed in science until the late 1980s, clashed against the new data obtained by sequencing first the mitochondrial and then nuclear DNA and, finally, collapsed.

Based on the currently available archaeological, anthropological, and genetic materials from the most ancient sites in Africa and Eurasia, scientists now trace the origins of humans of a modern anatomical and genetic type, Homo sapiens, to at least four types of hominins: Homo sapiens africaniensis (East and South Africa), Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Europe), Homo sapiens orientalensis (Southeast and East Asia) and Homo sapiens altaiensis (North and Central Asia). Evidently, not all of these subspecies have contributed equally to the formation of anatomically modern humans: Homo sapiens africaniensis featured the greatest genetic diversity, and it was he who laid the foundation for the modern human. However, the most recent data of paleogenetc research dealing with the presence of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in the gene pool of modern mankind have shown that the other groups of ancient people did not stand back either.

Based on the currently available archaeological, anthropological, and genetic materials from the most ancient sites in Africa and Eurasia, scientists now trace the origins of humans of a modern anatomical and genetic type, Homo sapiens, to at least four types of hominins: Homo sapiens africaniensis (East and South Africa), Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Europe), Homo sapiens orientalensis (Southeast and East Asia) and Homo sapiens altaiensis (North and Central Asia). Evidently, not all of these subspecies have contributed equally to the formation of anatomically modern humans: Homo sapiens africaniensis featured the greatest genetic diversity, and it was he who laid the foundation for the modern human. However, the most recent data of paleogenetc research dealing with the presence of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in the gene pool of modern mankind have shown that the other groups of ancient people did not stand back either.

Huge prospects for further development of the theory of anthropogenesis come from a new paleogenetic method for retrieving traces of ancient people from sediments, which was developed by the international team led by Prof. Pääbo. As of today, researchers have found both Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA in soil samples from Denisova Cave; importantly, they have discovered it in the layers containing no fossil remains. This evidence suggests that archaic people had lived here tens of thousands of years earlier than we previously thought.

Skeletal fragments of archaic people are very rare archaeological finds, so the new way of working with fossil DNA will tell us much more about the time when they lived and about their place of living and migrations. Perhaps, we will even hunt down where exactly the Denisovans lived: an analysis of the genome of modern people indicates that they lived somewhere in Asia, but we yet have no clue as to where and when, and their remains have so far been found only in one place – in Denisova Cave.

References

Derevyanko A. P. «I have the Soul of a Nomad» // SCIENCE First Hand. 2005. V. 4. N. 1. P. 114—125.

Derevyanko A. P., Shun’kov M. V. Where has Homo sapiens come from? // SCIENCE First Hand. 2016. V. 43 N. 1. P. 40—59.

Pääbo S. In search of lost genomes: from the Neanderthal to the Denisovan // SCIENCE First Hand. 2015. V. 65/66. N. 5/6. P. 20—35 [in Russian].

Shun’kov M. V. Past and present // SCIENCE First Hand. 2015. V. 65/66. N. 5/6. P. 6—19 [in Russian].